ALICJA BIELAK

VIDI DEUM FACIE AD FACIEM

EMBLEMATICS IN MARCIN HIŃCZA'S MEDITATIVE WORKS

|

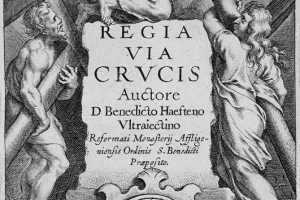

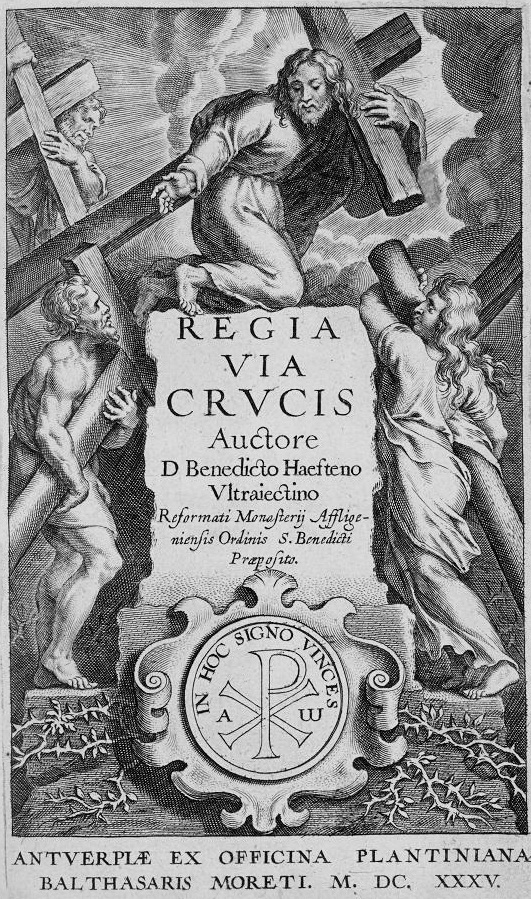

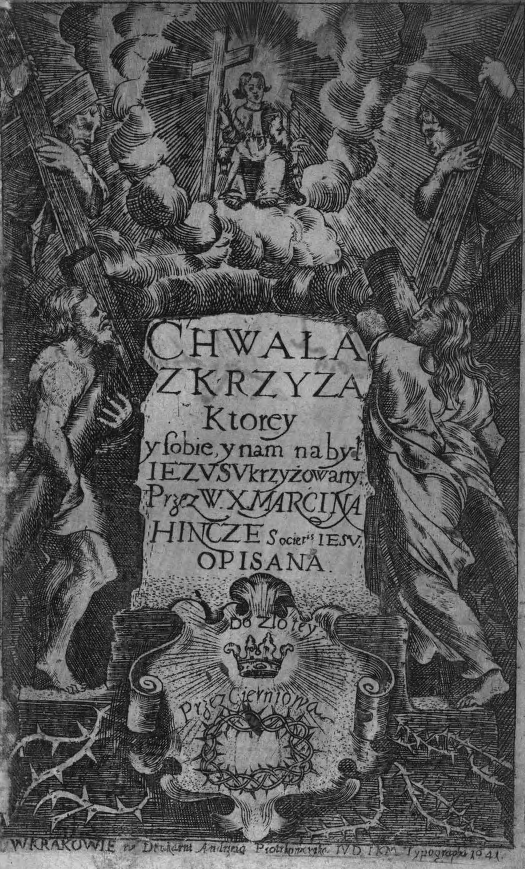

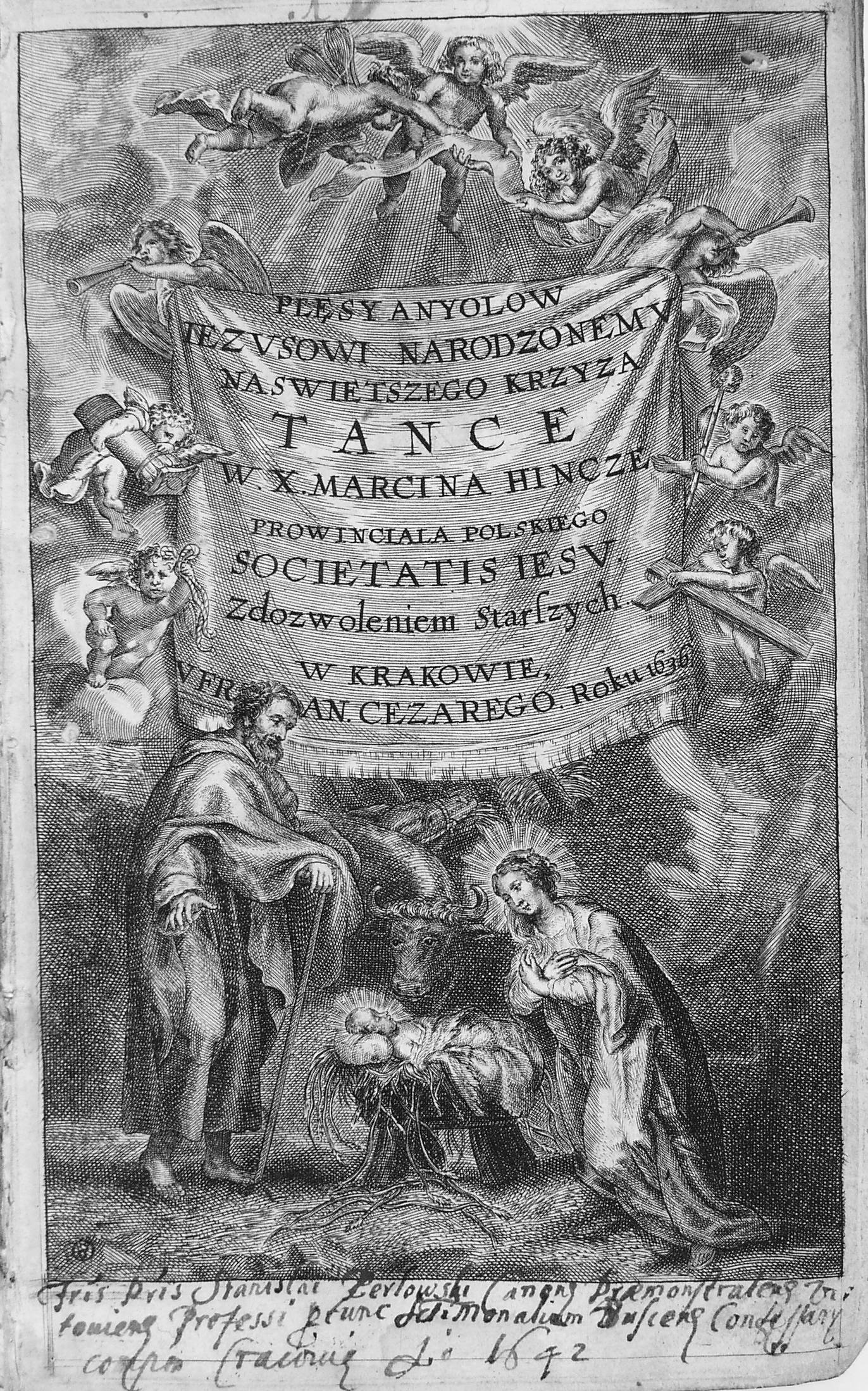

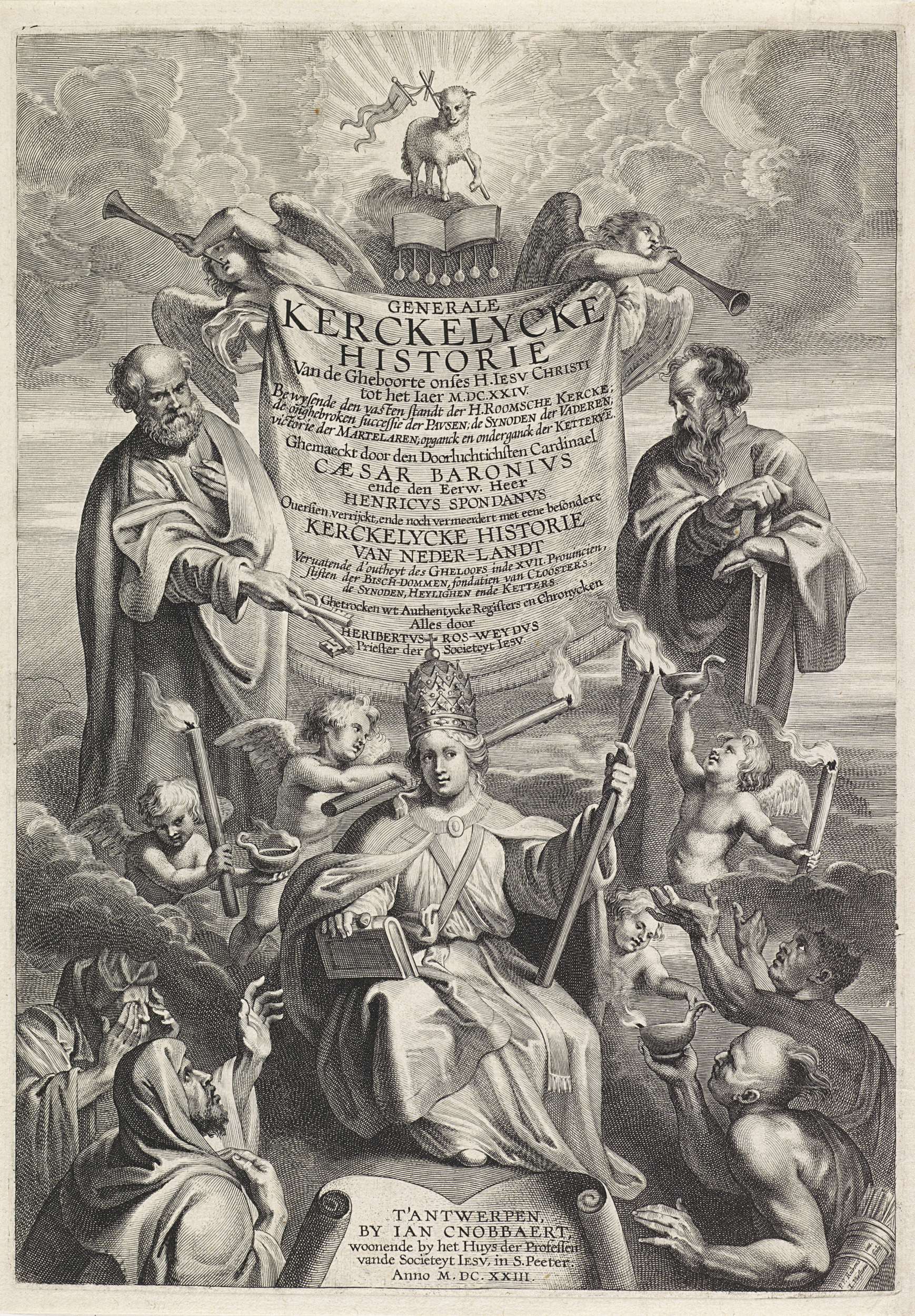

Les Emblèmes ou devises chrestiennes (Lyon 1567) by Georgette de Montenay, a Calvinist and lady in the court of Queen Joanne III of Navarra, is considered the first use of emblematics for religious purposes. After it was published, Catholic writers immediately realised how attractive and potentially useful for preaching this genre is. Thus, a subgenre of “sacred emblems” (emblemata sacra)[1] emerged. It mostly fascinated Jesuits, who published more emblematic volumes than any other intellectual movement. Around 1700 of their publications were emblematic, and if we were to draw a map of emblematic works created under the visible influence of a Jesuit model of piety or aesthetics, we would be obliged to add to that sum hundreds, if not thousands, of titles by lay authors and clergymen of different orders.[2] While pondering upon the various ways in which “Jesuit” emblematics were realised’, we should not forget about the specific status given to representatio in Ignatian piety: the realm of visible things was considered to have aesthetic, didactic and mnemonic values, but also an epistemological function: visibilia was always to point towards the invisible. All of creation was, according to Ignatius of Loyola, simply a veil for the transcendental – the realm of spirits both good and evil. A Christian should learn how to read their actions and distinguish between them. That way, he will be able to follow only what was given by God.[3] Emblem, watchwords and symbols became the objects of theoretical contemplation for Jesuits who, aside from noticing their persuasive character and using them for inventio (they were equated with imago figurata, a rhetorical trope), considered the possibility of using them as stimuli for explaining reality created ad imaginem Dei – in God’s image (Gen 1:26). Antoine Girard, a Jesuit, in the preface to his Les Peintures sacrées sur la Bible (Paris 1653) considered the Ignatian recommendation of “finding God in all things” the very core of The Society of Jesus’ thinking, seeing it as a call to use even the smallest elements of earthly matters for spiritual elevation towards God and remaining at his service. The theory of representatio, developed by Jesuits, assumed a strict parallel between the earthly world – a labyrinth through which the lost human soul paces – and the actual heavenly reality. The theory is too elaborate and complex to be explained here; I will limit myself to the description of issues that can aid in understanding the main assumptions and aims of the following sketch – the meditative and emblematic works of a Polish Jesuit, Marcin Hińcza.[4] Hińcza wrote six volumes of meditation in prose. Two of them were designed as emblematic cycles: Plęsy Jezusa z Anjołami (Jesus’ Frolics with the Angels, 1636–1638) and Chwała z Krzyża (Glory of the Cross, 1641). Illustrations for the Glory were taken by the publisher, Andrzej Piotrkowczyk, from several Dutch collections, mostly from Amoris divini et humani antipathia by Louis of Leuven[5] and Via regia Crucis by Benedict von Haeften (1588–1648).[6] The titular page was originally designed by Peter Paul Rubens himself (and made by Cornelis Galle). In the Cracovian publishing house it was altered significantly, probably at Hińcza’s request, so that the titular page would reflect the theological dimension of the piece. Jesus with a cross during the Passion (ill. 1) was replaced by the Infant Jesus sitting on a throne with a cross in his hand (ill. 2). This measure reflects quite well the style and meanings of Hińcza’s works; they focus almost entirely on the new-born Saviour. As has been determined by Anna Trejderowa, the 14 emblematic engravings placed in the Jesus' Frolics… were all made by a lesser known engraver from Theodore Galle’s school, Egidius van Schoor (Aegidius van Schoor or Gillis Verschoren).[7] Among the inspirations for them we can list Cornelius Thielmans and Augustus Suarez, but also such famous artists as Peter Paul Rubens, Antoon van Dyck, Joos de Momper, Otto van Veen (Venius) and other Flemish painters.[8] It is also worth mentioning that Van Schoor cooperated with Michael Snijders in publishing the aforementioned famous Amoris divini et humani antipathia as an engraver. Thanks to research conducted in Belgian archives it was possible to determine that the titular page of the Cracovian edition is a compilation of graphic motifs from books issued by Dutch publishing houses: angels blowing trumpets and presenting the cartouche or a cupid holding a candle; these motifs were probably taken from Generale Kerckelycke historie van de gheboorte onses H. Iesu Christi[9] by the Jesuit Cezary Baronius. One of the flying cupids with a column comes from an engraving titled Virtus Inconcussa, which opened a famous collection of Otto Vaenius’ Horatiana emblemata,[10] the sacred family with three angels above them comes from a woodcut by Bolswert Schelte Adamsz inspired by the Rubens painting (ill. 3-7). Connections with the aforementioned houses are not surprising if we consider the fact that printers from Cracow had close dealings with Dutch publishers.[11] A glance at emblematic prints stored in the archives, dating from the second half of the 16th century and the first decades of the 17th, legitimises the thesis of Hińcza having commissioned Van Schoor to create a series of engravings for Jesus' Frolics…. The topic of the volume is entirely original and there is no book from that period that would use a similar topic or graphics: presenting the crucified Christ as a child, not as a grown man, with angels revelling around the Cross. There is a strict connection between the text and the illustrations. The main subject of Hińcza’s meditative works is the birth (both primeval and earthly, from the womb of Mary), life, death and ascension of Christ with stress on the theological dimension of the Nativity and Incarnation. In two of the aforementioned volumes and in different ones created as part of Hincza’s early work (see Rozmyślania o dziecięctwie Pana Jezusowym [Thoughts on the childhood of Jesus], Cracow 1636) the dogmatic aspects are not discussed according to the vocabulary and rhetoric of theological treatises (so it is futile to look for terms such as “incarnation”[12] and developed references on the margins), although they consistently develop the concept of Jesus as Logos. It is certain though that Hińcza, as a professor of moral theology (he studied philosophy in Ingolsztadt, Rome and Kalisz and lectured in Cracow) was fully aware of all the nuances of Church dogma; for some reason, however, he decided not to refer to them directly in these works. He preferred to turn the dogmas of faith into stories or concepts. Reasons for this course of action can be found in the audience which he chose for his books, which were supposed to nourish piety in laymen. He stressed this himself in the prefaces, saying: “do not think I show these frolics to conventuals: they are both for preachers and for laymen to enjoy”.[13] Despite having drawn emblems from Regia via Crucis, a piece which expresses the idea of the bride’s soul travelling to find God’s love, a concept also known from Pia desideria, Hińcza does not present a simple reference to the themes and subjects of these works. The Glory of the Cross is almost a repetition of contents from the author’s earlier work – the Frolis…. The list of contents in the latter is an enumeration of values consequent on choosing the Cross – a symbol of salvation’s entire history – as one’s signpost: “enlightenment from the Cross”, “simplicity from the Cross”, “defence from the Cross”, “all venerations from the Cross”, etc. Similarly to Von Haeften, Hińcza enunciates the theology of the Cross, displaying its redemptive power in God’s plan,[14] but – which is unusual – does not stun the reader with the picture of the suffering Christ. To the meditator’s surprise, the Infant Jesus and all the angels surrounding him seem to rejoice at any sign of the nearing Passion. “Now the holy Angel creates an image of Christ’s future disgrace”. An emblematic icon accompanying the meditation acts as a compositio loci[15] and serves to make the reader emotional. At the beginning of every meditation, Hińcza observes the angel’s behaviour, is surprised by it and even execrates them: “do you know not, what tree is that? The one that will kill your Lord, and you are happy that he will die suffering?”, “you will get what is coming to you; believe me, the joy will turn to grief”.[16] By enumerating paradoxical images (birth – death, child – corporal punishment, Mary’s care – the seemingly aggressive behaviour of the Angels), Hińcza shows the reader that human perceptive abilities are not capable of processing the real meaning of the world that is a part of the Salvation plan. Every action of the angels Hińcza explains by their servitude to Christ on his way to fulfil God’s intentions. That plan only seems horrifying to people who still live according to categories of earthly reality. Hińcza’s angels then have the function of Christ’s perfect helpers, an image concurring with Ignatian piety: Loyola called angels God’s special help (auxilium speciale) due to the fact that they help men find the right path. It is worth stressing that this was a time of development of personal piety linked to the idea of guardian angels. Jesuits stressed the moral necessity of devoting oneself to one’s angel and the crucial role of mutual love of angels and humans in the economy of Salvation. To argument in favour of everyone having a personal guardian angel, they recalled the words of Christ (Mt 18:10): “See that you do not despise one of these little ones. For I tell you that their angels in heaven always see the face of my Father in heaven”[17]. The idea of seeing God the Father face to face implies an eschatological dimension: a soul, upon being saved, will be with the angels and will be able to look upon God’s face as he is being praised by heavenly hosts (Mt 18:10; see also Ex 33:11). But, as Christian mystics declared and Catholics of the post-Tridentine era repeated, following St. Paul, Jesus became visible for humans on earth to save them in the name of marital love and to show his face, which is – paradoxically for the Christological representation – at the same time the face of his Father (cf. 1 J 3, 2).[18] Hińcza also stresses this change in God’s visibility that occurs with the coming of Christ. He recalls of those enlightened by the brightness of the crucified Christ that “they [Apostles – A.B.] then enlightened the world and brought it to realise the truth (1 Cor 1)”. He also notes that the angels “all trembled before Thy glory in heaven, and on earth it is as if they have forgotten it […] God forbid they should step down from the place designed for them, away from his visage – all would fall into the abyss. Everyone knows what happened to the numerous angels who thought of being equal to the Creator”.[19] The idea behind Frolics... corresponds to Robert Bellarmin’s De Ascensione mentis in Deum (1615), translated into Polish by Kasper Sawicki in 1616.[20] The cardinal describes fifteen consecutive steps to knowing God, starting with his creation (which God – himself unable to see, according to Bellarmino – created for humans), and it ends with the description of the sun as the most beautiful thing visible, which corresponds to the cosmological vision introduced at the beginning of Hińcza’s piece: a cosmic dance of stars (angels) and moon (Mary) around the sun (Jesus, also described as “brightness”).[21] Bellarmino adapted a neo-Platonic mode of thinking, saying that looking at sun and stars brings joy and their movement resembles dancing: “all of them in their beautiful order run, tireless, in a circle, looking as if they were dancing”.[22] The next steps of recognition are only a part of the invisible world: a man should initiate this stage by looking into his own soul (the part most resembling God’s nature), then consider the nature of angels and, finally, the features of God (the Jesuit keeps stressing the role of sight in all these stages: to know God one must look upon the angels). An angel’s sight is vastly different from a man’s, because “an angel can immediately perceive and understand what he sees, and realise what comes of it”.[23] In conclusion, Bellarmino teaches us that the simplest way to the Kingdom of Heaven is “where we perceive together with the angels, as they always look upon the Father’s face”.[24] In the Frolics... angels repeat the gesture of God’s heavenly worship, the possibility of looking upon His face: “they do not take their eyes from Him, and the more different from the divine and human nature his features become, the more intently angels look at Him, to learn this odd secret – that God even in such a humbled form is full of greatness”.[25] The soul, looking at angels while praying, is at first surprised and only later starts to understand that it should follow them in their contemplation of Jesus (Hińcza also maintains the metaphor of the cosmic dance, which we cannot address here).[26] Looking at Christ, it follows his example but also wants to be seen by its Beloved as pure and like Him: “Oh Man full of love (= Jesus – A.B.), make it so that all heavenly and earthly beings could say about me that ‘this man wants to be like You in his loving’”.[27] The dynamics of exchanged looks between the meditating soul and Jesus, described vividly in Hińcza’s works, is developed for example in the meditative emblematic works of the Spanish humanist and theologian Benito Arias Montano. In his cycle entitled Divinarium nuptiarum conventa et acta (Atverpiae 1573),[28] Montano, basing his perspective on the Song of Songs, writes out a drama taking place between the Bride (Sponsa) – i.e. the Soul – and the Groom (Christ). For the marriage to happen, however, the soul must be cleansed of its sins and understand its paltriness. Wisdom Personified (Scientia) tells her to look into a mirror that will allow her to see her true visage. The Bride sees all the futility of the world, vanity and craving for earthly honours. The Bride, exhausted by this sight, rests upon the bosom of Wisdom and then looks upon another mirror in which she only sees the face of Christ. The paraenetic dimension of this visage is an obvious context for the collection: speculum vitae Christi becomes synonymous with meditation itself. Only when the Bride decided to live virtuously, following the example of Christ, wiped out her own, sinful reflection from her soul and replaced it with His face in the name of imitatio Christi, does she experience marital love and connect with the beloved.[29] The words of Paul from the First Letter to the Corinthians (13:12) provide context for these words. He says that on earth “For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known” (ESV). Hińcza acts similarly when showing the moment when Mary looks into Christ’s face: “she sees the awfulness and sin taken from human faces stain the visage of her Son […] She will see her soul and know that for that ugliness of her Son’s she has an ornament above all others”.[30] The ugliness is a result of Christ’s whipping, and becomes the reason for human righteousness – thus an ornament. This is compatible with the aim of Ignatian meditation, which is supposed to incarnate Christ’s presence – his re-presentation in the memory, mind and heart of the meditating person – in order to take an example from him (imitatio) not only by means of compassion (compassio), but also by observation, which drives the meditator to understand and feel guilt: “Every soul which glances upon the tortured Christ will see that he has been beaten and hurt for them and by them”.[31] The moment a person understands that Jesus died because of his love for people (the Ignatian via illuminativa), he will cleanse himself of his sins (via purgativa), and then he will start to imitate Christ (via unica): “strive to be like Christ, struggle to follow him, for he is given unto you as an example”.[32] Angels are for Hińcza an example of the perfect spectators, subjects and admirers of Christ. They gaze upon him incessantly and joyfully, repeating the act of adoration in heaven of the first person of the Trinity (ill. 9). Christ’s descent (the descent of the Logos) is an act of his adoration and love for men: he puts himself in plain sight so that man can follow his example in his earthly peregrination. A glance at the role of sight in the meditative works of Hińcza makes it clear that he was perfectly acquainted with the problems explored by Jesuit theologians and artists, whose works he developed so skilfully. In the context of the aforementioned Dutch emblematic art, Hińcza was certainly well acquainted with contemporary artists, who not only borrowed from others, but were also able to rework their art. Moreover, like other Jesuit authors he could be creative in the use of emblems not just as illustrations but also as performative tools for the action of seeing, so important due to the epistemological aspect of Ignatian meditation and its theological connotations.

Translated by Zofia Marcinek

[1] In the titles of emblematic collections and in the prefaces to those volumes we encounter the term emblema sacra, which denotes a broad and differentiated spectrum of realisations: moralising symbols and watchwords (see Emblemata sacra by Daniel Cramer from 1624 or Guillelmus Hesius’ Emblemata sacra de fide, spe, charitate from 1636), illustrations of events from the gospels (a famous, prolifically reissued collection by Jeronimó Nadal entitled Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia), illustrated lives of saints and martyrs, ascetic collections developing piety, and others. [2] Corpus Librorum Emblematum: The Jesuit Series, ed. P. M. Daly, G. R. Dimler, University of Toronto Press, vol. I–V: Toronto 199–2007. [3] R. Dekoninck, Ad Imaginem: Status, fonctions et usages de l’image dans littérature spirituelle jésuite du XVIIe siècle, Genève 2005. [4] A full analysis of the theme of the Incarnation and of its influence on the Jesuit theories of representation and image has been conducted and propagated by two excellent researchers: Ralph Dekoninck and Walter S. Melion. See R. Dekoninck, op. cit.; W.S. Melion, Meditative Art: Studies in the Northern Devotional Print, 1550-1625, Philadelphia 2009; Meditative art Image and Incarnation, ed. W. S. Melion, L. P. Wandel, Brill, 2015; Jesuit Image Theory, ed. W. de Boer, K. A. E. Enenkel, and W. S. Melion, Brill, 2016. [5] Ludovicus van Leuven, Amoris divini et humani antipathia, Apud Michaelem Snyders, Antwerpiae 1626, 1629. [6] Benedictus von Haeften, Via regia Crucis, Antverpiae: ex officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1635. The basics for the icons in Boetius of Bolswert’s works in the case of Chwała z Krzyża and the fact that the engravings for Plęsy were made by Egidius van Schoor were noted by Anna Treiderowa; see Ze studiów nad ilustracją wydawnictw krakowskich w wieku XVII (z drukarń: Piotrkowczyków, Cezarych, Szedlów i Kupiszów), “Rocznik Biblioteki PAN w Krakowie”, 1959, 5, p. 37–38. See also J. Pelc, Słowo–obraz–znak. Na pograniczu literatury i sztuk plastycznych, Universitas, Kraków 2002, p. 196–204. [7] See Hollstein et al, vol. 26: 1982, p. 47–49. He does not count Frolics... among the books illustrated by Van Schoor, just as he does not mention such pieces as De naer-volginge des doodts ons heeren Iesu Christi by Nicolaus Georgius (Tot Brusel: bij Ian Mommaert, 1650) or the collection by Nicolaus Ianssenius entitled Vita P. P. Dominici ordinis praedicatorum fundatoris (apud Heicum Aertssium, Antverpiæ 1622), which we know were made by Van Schoor because of his signature: “G. V. Schoor f[ecit]”. Van Schoor is also not mentioned in encyclopaedias of Dutch printing and engraving. [8] Kunstschilders, beeldhouwer, graveurs en bouwmeesters, Gebroeders diederichs, v. 2: P–S: ed. C. Kramm, Amsterdam 1861, p. 96. [9] C. Baronius, Generale Kerckelycke historie van de gheboorte onses H. Iesu Christi, Ian Cnobbaert, T’Antwerpen 1623 (engraver: L. Vorsterman). [10] O. Vaenius, Horatiana emblemata, apud Philippum Lisaert, Antverpiae 1612. [11] The editor of Glory..., Andrzej Piotrkowczyk, went to the Netherlands himself as the preceptor of the Radziwiłł family and cooperated with the greatest men of the contemporary literary scene. In Leuven he studied rhetoric in Erycius Puteanus’ school; the latter praised him in personal letters to Daniel Heinsius (see M. Czerenkiewicz, Belgijska sarmacja, staropolska Belgia, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Warszawa 2013, p. 61). See also P. Buchwald-Pelcowa, J. Pelc, Rola jezuitów w kształtowaniu się związków emblematyki polskiej z emblematyką niderlandzką, “Barok”, 2003, nr 20, p. 9–32; M. Malicki, Repertuar wydawniczy drukarni Franciszka Cezarego starszego 1616–1651. Część 1, Wydawnictwo Księgarnia Akademicka, Kraków 2011; W. Ptak-Korbel, Andrzej Piotrkowczyk II, in: Drukarze dawnej Polski od XV do XVIII wieku: praca zbiorowa, vol. 1: Małopolska, p. 2: Wiek XVII–ZVIII, vol. 2.: L–Ż i drukarnie żydowskie, ed. J. Pirożyński, Kraków 2000. [12] To clarify, in the entire 700-page book the phrase “the incarnated Word ” appears once (M. Hińcza, Plęsy… Kraków 1638, p. 349). [13] Ibid., p. 31. More consistent, casuistic theological investigations can be found in his older works – the meditative volume Matka Bolesna Maryja and Glos Pański… Thus, when analysing pieces by a doctor of theology – including those from the 1630s, which are repetitive and very sensual, and which apply all spiritual experiences to human senses (in accordance with the Jesuit applicatio sensuum rule) – we should also try to find messages and arguments not expressed explicitly. [14] Similar contents can be found in the writings of Kasper Drużbicki, with whom Hińcza was acquainted. See J. M. Popławski, Kaspra Drużbickiego teologia Krzyża, Redakcja Wydawnictw Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego, Lublin 1997. [15] On the functions and types of composition of place in Loyola’s Spiritual exercises see especially P.-A. Fabre, Ignace de Loyola: Le lieu de l’image. Le problème de la composition de lieu dans les pratiques spirituelles et artistiques jèsuites de la seconde moitiè du XVIe siècle, Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales et Librairie Vrin, Paris 1992. Nota bene Loyola often demands in addition that readers should picture themselves in the presence of God, saints and angels. [16] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 90, 657, 656. [17] At the time, angelology in the Jesuit Society was mostly pursued by, among others, Jeremias Drexel and Cornelis a Lapide. Originally it was initiated by Bellarmin’s favourite, Alojzy Gonzaga, who died before his time; Gonzaga was the author of angelic meditations. Trevor Johnson stressed that angelology from the turn of 16th century often contained motifs that may seem dogmatically controversial. See T. Johnson, Guardian Angels and the Society of Jesus, in: Angels in the Early Modern World, ed. P. Marshall, A. Walsham, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, p. 191–213. [18] The Holy Face and the Paradox of Representation, ed. H. L. Kessler, G. Wolf, Nuova Alfa Editoriale, Roma 2000; W.P. Melion, Haec per Imagines huius mysterij Ecclesia Sancta [clamat]: The Image of suffering Christ in Jerome Nadal’s Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia, in: J. Nadal, Annotations and meditations on the Gospels, v. II: The Passion narratives, tr. and ed. F.A. Homann, preface by W. P. Melion, Saint Joseph’s University Press, Philadelphia 2007, p. 1–73. [19] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 29–30, 89. [20] R. Bellarmino, De Ascensione mentis in Deum per scalas rerum creatarum opusculum, Ex Officina Plantiniana, Antverpiae 1615; R. Bellarmino, Piętnaście Stopni, po których człowiek, zwłaszcza krześcijański, upatrując Pana Boga w stworzeniu rozmaitym, przychodzi do wielkiej znajomości jego, tr. Kasper Sawicki, Kraków 1616. [21] On the cosmic dance of angels in Frolics… see A. Bielak, Taniec na Golgocie w medytacyjnym zbiorze „Plęsy Jezusa z aniołami” Marcina Hińczy, “Tematy i Konteksty” 2016, nr 6 (11), p. 302–316. [22] R. Bellarmino, Piętnaście stopni..., p. 112. [23] Ibidem, p. 126. [24] Ibidem, p. 128. [25] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 42. [26] On the development of the subject of stellar angelic hosts praising God in the heavens see J. Miller, Measures of Wisdom. The Cosmic Dance in Classical and Christian Antiquity, University of Toronto Press, Toronto-Buffalo-London 1986, p. 345–360, 391–401. [27] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 455. [28] The cycle may be found in the volume A. Montanus, Christi Iesu vitae admirabiliuque actionum speculum (engraver: P. Galle). [29] See W. P. Melion, Love, Judgment, and the Trope of Vision in Benito Arias Montano’s “Divinarum nuptiarum conventa et acta” and “Christi Iesu vitae admirabiliumque actionum speculum”, in: ibid., The Meditative Art. Studies in the Northern Devotional Print: 1550–1625, Saint Joseph’s University Press, Philadelphia 2009, p. 39–105. [30] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 326–327. [31] Ibidem, p. 456. [32] Ibidem. |

Ill. 2. M. Hińcza, Chwała z Krzyża której i sobie, i nam nabył Jezus ukrzyżowany, w drukarni Andrzeja Piotrkowczyka, Kraków 1641, titular page (Chełmska Biblioteka Cyfrowa)

Ill. 7 7. M. Hińcza, Plęsy Anjołów Jezusowi Narodzonemu, naświętszego Krzyża tańce, u Franciszka Cezarego, Kraków 1638 (University of Warsaw's Library, sygn. Sd.712.583)

|