BARTŁOMIEJ CZARSKI

ANDREAS ALCIATUS AND BONA SFORZA:

IN PURSUIT OF THE OLDEST TRACES OF „EMBLEMATUM LIBER” IN POLAND

|

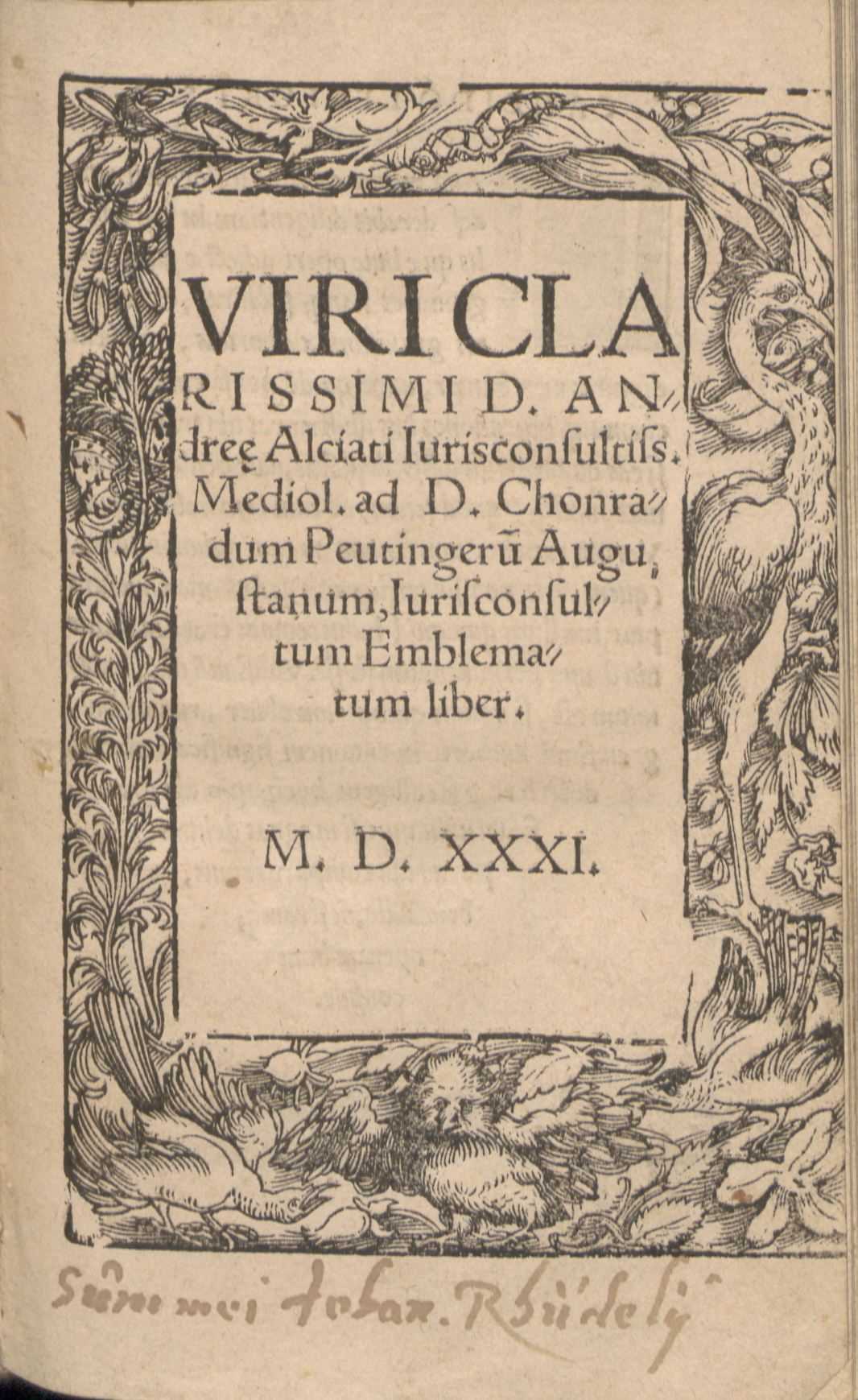

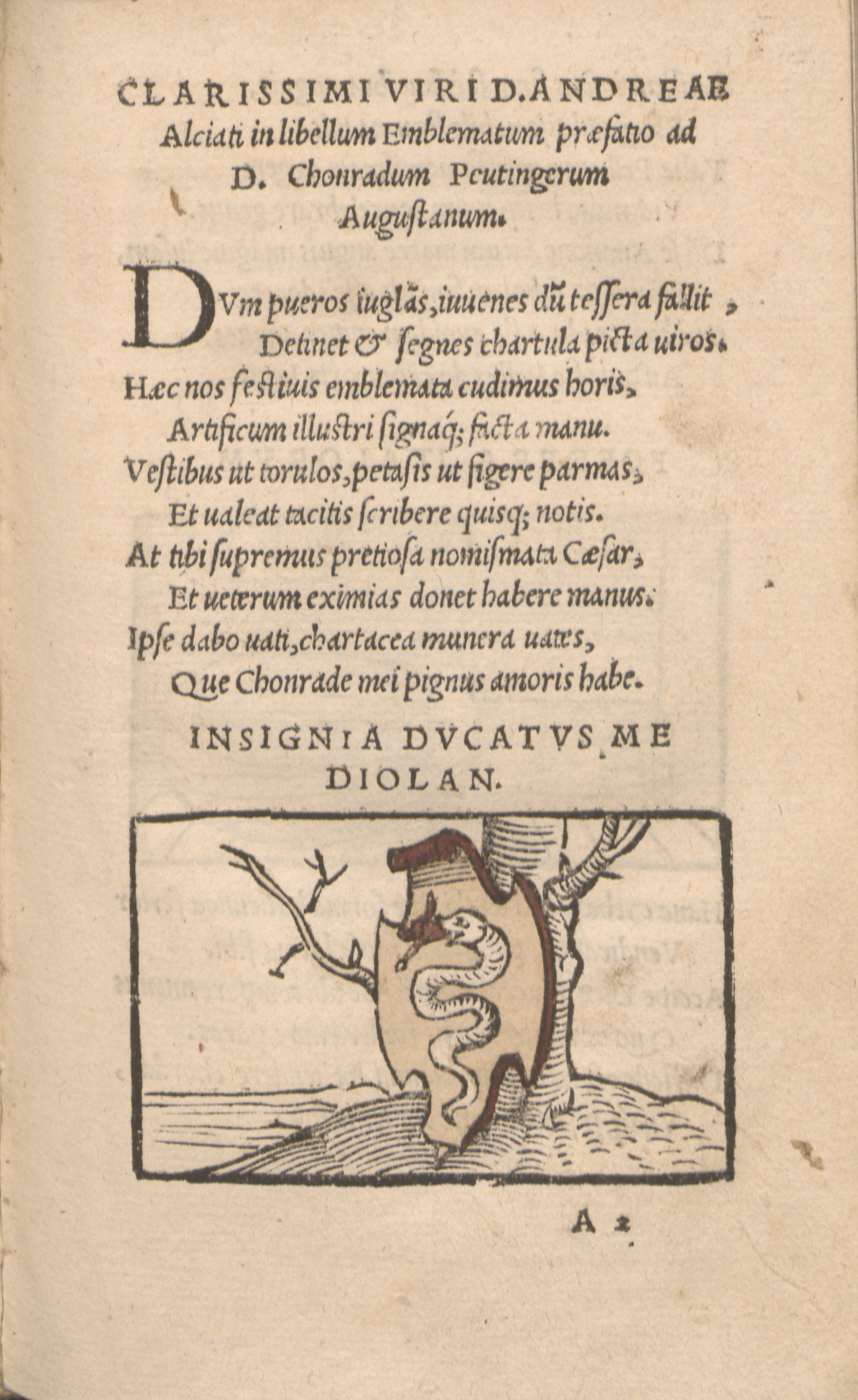

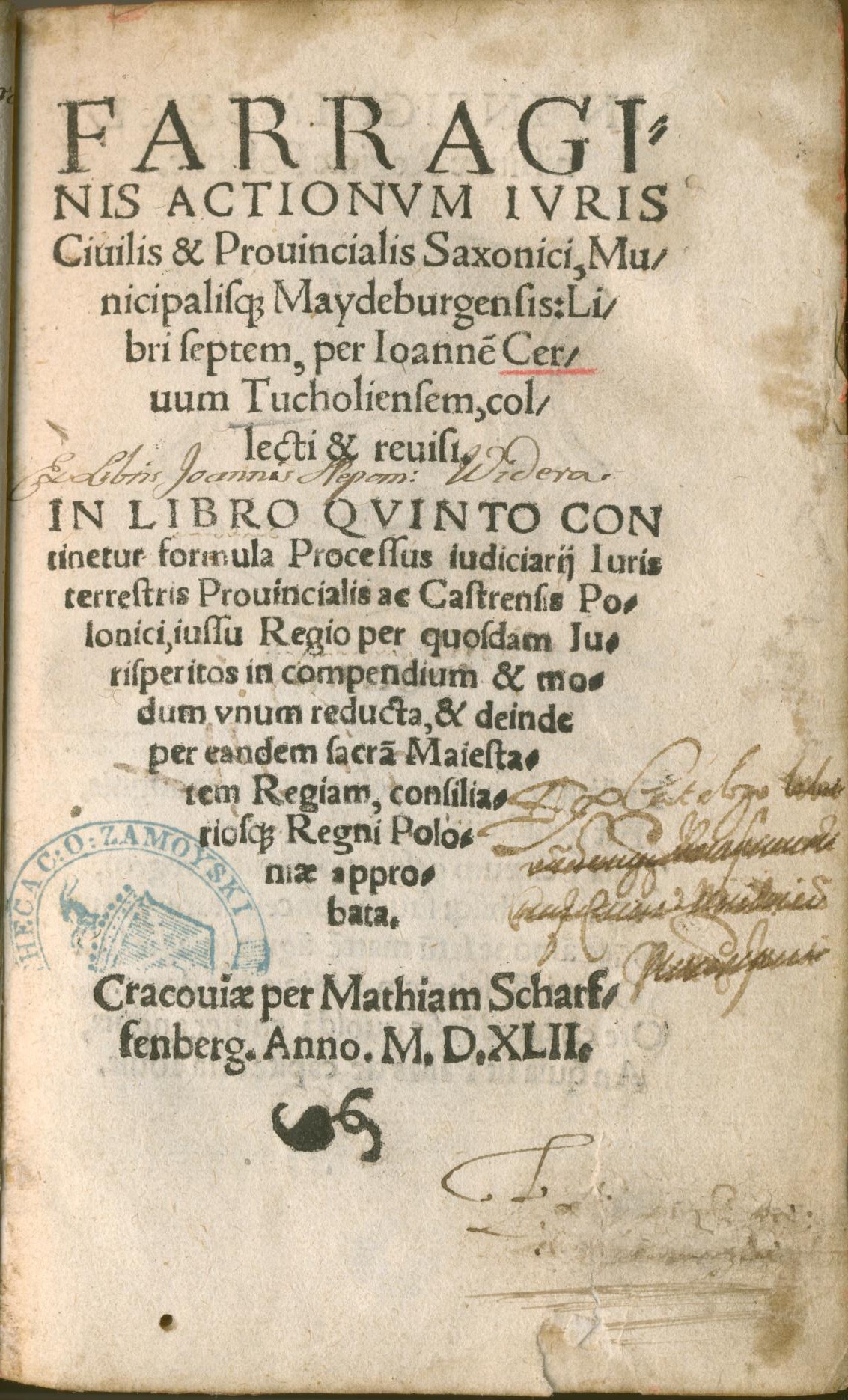

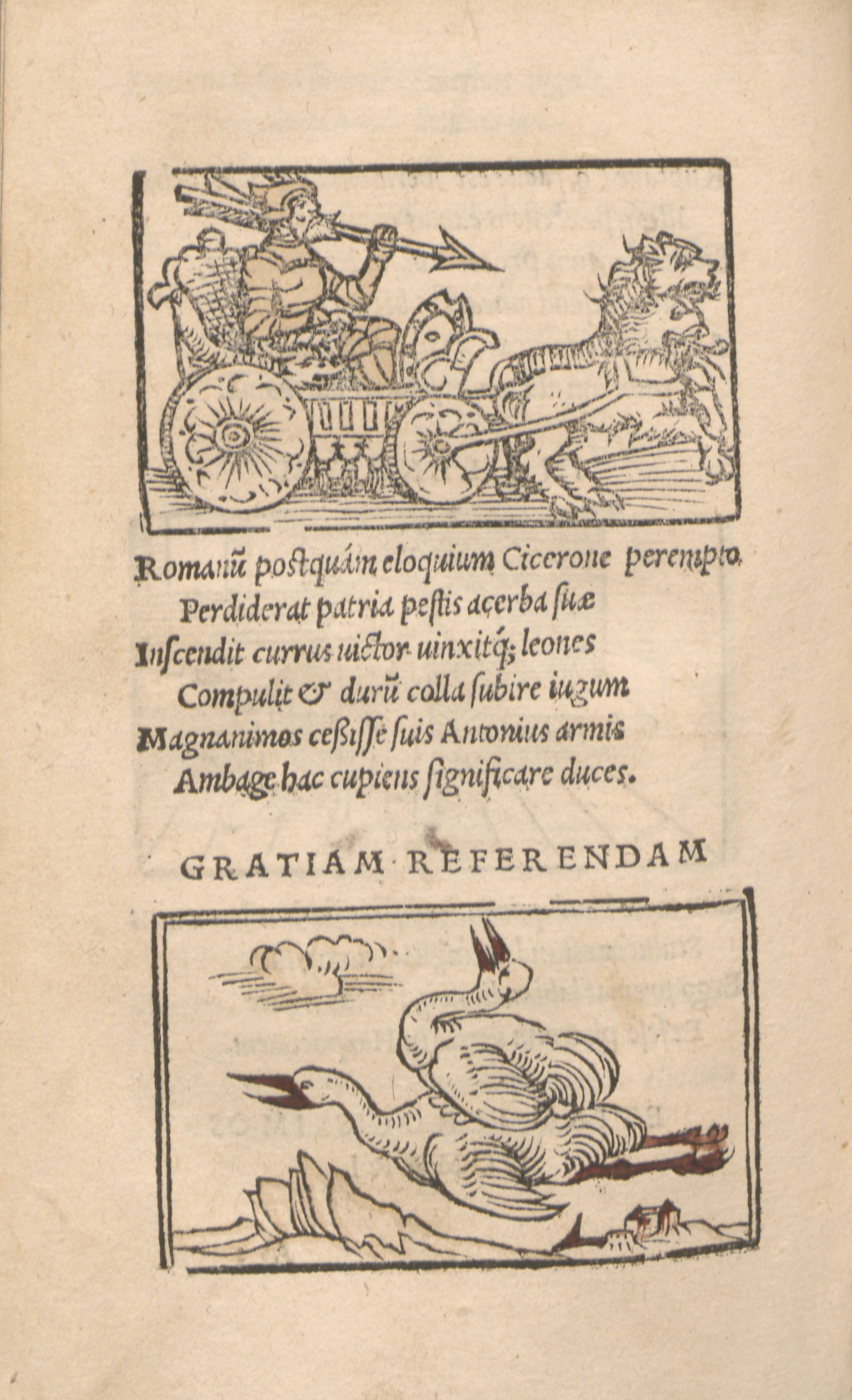

Verbal and visual compositions in Polish print appeared very early, usually in the form of stemmata – verses adorning coats of arms. They were usually accompanied by a wood engraving representing an emblem relating to the epigram in question.[1] It was also common to add verses to images of saints or various icones. The oldest cases can be traced back to the dawn of the 16th century,[2] and are thus older than the 1531 Emblematum Liber[3] by Andreas Alciatus (Andrea Alciato/Alciati), a collection commonly considered to be the first emblem book: the history of European emblematics begins with its release (Ill. 1). The author was a famous lawyer, a lecturer in Padova, Bologna, and Ferrara, as well as in France, in Avignon and Bourges.[4] He is mostly remembered for this initially minor volume containing 104 emblems (of which 97 are illustrated). It was published for the first time in the publishing house of Heinrich Steyner and later reissued and extended (finally reaching 212 emblems) by various editors and interpreters. The estimated number of issues published by the end of the 17th century is over 170.[5] The collection contains epigrams inspired by traditional European motifs drawn from mythology, the Holy Bible, fables, Greek and Roman literature and ancient relics such as architectural details, gems and coins preserved until the 16th century. At that time, these objects were an object of interest and passion to intellectually sophisticated collectors.[6] It is a topic of discussion among modern scholars whether the graphics were chosen by the author himself, or whether someone else decided which graphics would accompany the epigrams.[7] Regardless, the engravings became a fixed part of the emblems. Together with the verse and the titular motto, they constitute the three elements of the most common emblematic structure. Some of Alciatus’ works, partly because of the accompanying engravings, bear resemblance to the aforementioned stemmata. The opening poem could be mentioned here: in the editio princeps it was entitled Insignia ducatus Mediolanensis [The emblem of the Milan Duchy] (see ill. 2). In later editions it was treated as a form of dedication and was meant for Prince Maximiliano Sforza, as can be deduced from how the title was modified: Ad illustrissimum Maximilianum ducem Mediolanensen (To the honourable enlightened Maximiliano, Prince of Milan).[8] Alciatus had an inestimable influence on European literature. After his publications, emblems started to appear in the works of various authors, and to have a great influence on contemporary culture. Nonetheless, despite considerable evidence that Emblematum Liber was well known in 16th-century Poland, it is hard to trace its first direct influence on Old-Polish literature. Since heraldic compositions became a more popular and prolific emblematic form in Poland than anywhere else, one might suspect that Alciatus’ most famous compositions would be the ones related to heraldic motifs. But it is also important to remember that the appearance of stemmata and emblematic verse is not limited to Poland. They can be encountered elsewhere, and also earlier than in the Kingdom of Poland. One such example is Hieronim Wietor, a Viennese printer who later moved to Cracow and launched a prosperous publishing house there.[9] It seems reasonable to suppose that it was his books, largely meant for the Polish publishing market, that made emblems so popular in Cracow. Other publishers soon became interested in them as well – Florian Ungler,[10] the Szarffenbergs, and Jan Haller,[11] who was a publishing monopolist for quite some time. Even if heraldic compositions in Poland can be dated earlier than the official birth of European emblematics, it is valuable to try to find the earliest instances of the reception of Alciatus’ work, if for no other reason than the volume’s status as the first emblematic publication. Verses adorning coats of arms became fashionable at the beginning of the 16th century. It is for this reason that the above-mentioned emblem with a dedication, created upon the coat of arms of the Milanese royal family, drew attention in Poland. Its first uses can be traced back to 1542, just 11 years after Emblematum Liber was published. Cracovian printer Maciej Szarffenberg used it as a stemma added to a special dedication for Queen Bona Sforza, in a legal treatise written by Jan Tucholczyk (Ioannes Cervus) entitled Farraginis actionum iuris civilis et provincialis Saxonici municipalisque Maydeburgensis libri septem[12] (Ill. 3). Interestingly, the circumstances of this publication are criminal, because Szarffenberg stole a new version of Tucholczyk’s text from the workshop of Helena Unglerowa (the wife of Florian Ungler) and published it in 1539, before Unglerowa had time to release her own version.[13] Unglerowa lodged a complaint against Szarffenberg to the City Council and as a result the case came before the royal court. Thanks to the intervention of Queen Bona, Szarffenberg ultimately managed to avoid serious consequences. In gratitude for her protection, the next edition of Tucholczyk’s dissertation (in 1542) was dedicated to the wife of Sigismund the Old. The Cracow typographer decided to reprint the work in 1546; on this occasion also, he included the stemma with Alciatus’ epigram, in exactly the same form as in the 1542 publication. It is difficult to clearly explain the reason for the queen’s intercession. It was perhaps due to efforts on the part of the printer’s wife, Helena Szarffenbergowa, who enjoyed the sympathy of the queen in later years also.[14] Only the verse from Alciatus’ emblem was used. The publisher added a wooden engraving of the Sforza family crest to it and – obviously – omitted the title. The epigram used in the new context could no longer be associated with Milan or Prince Maximiliano. It was meant to draw attention to the Polish queen. It may also be the reason why the verse was reproduced without mentioning the author’s name – to erase the primary meaning of the emblem completely. The verse itself explains their family crest in an allegorical manner, praising the family:

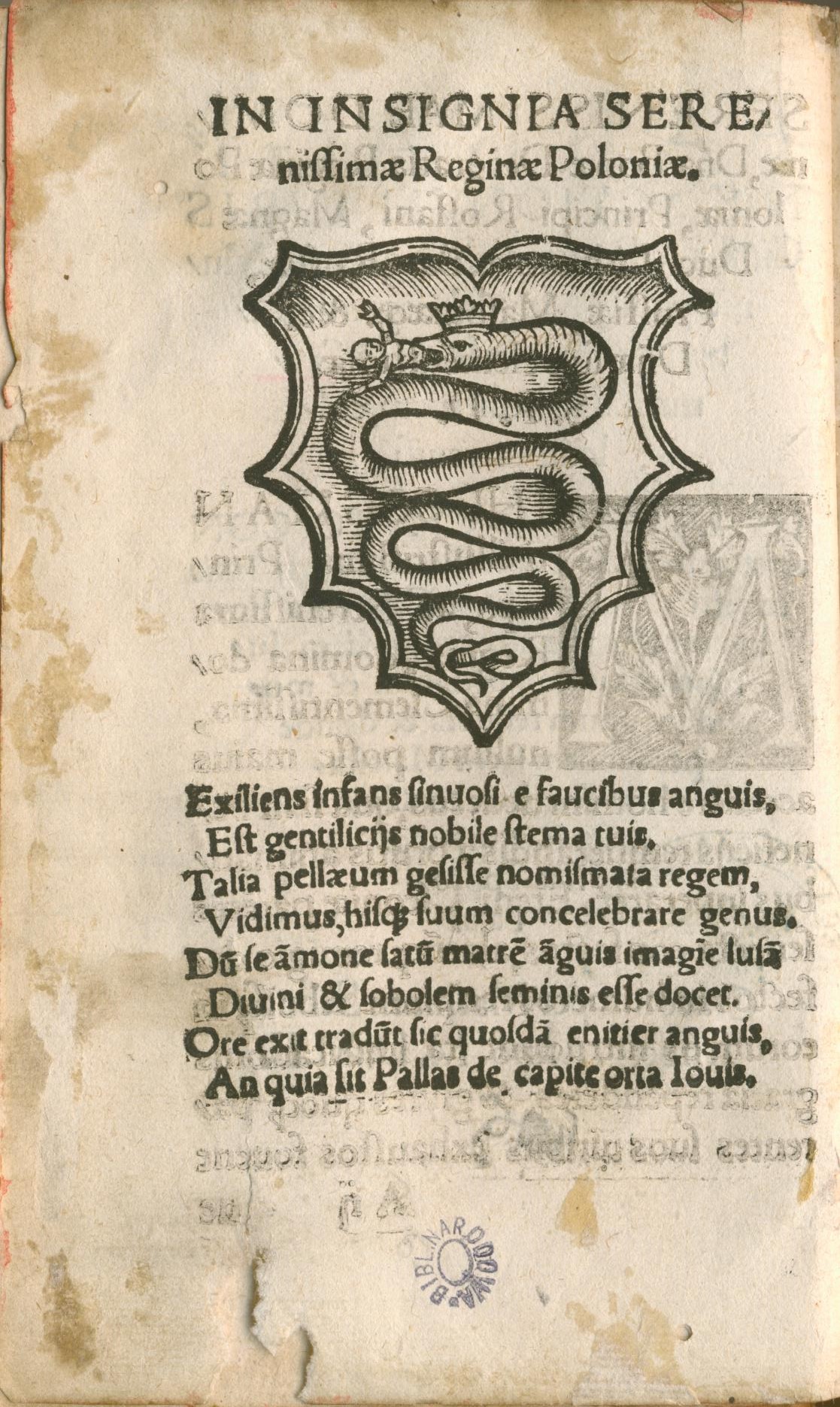

Exiliens infans sinuosi e faucibus anguis,

[An infant springing from the jaws of a curling snake is your family’s noble device. We saw the Pellaean king had made such coins, and had celebrated with them his own descent. It teaches that while he was sown from the seed of Ammon, his mother was fooled by the image of a snake and that he was the offspring of divine seed. He comes forth from the mouth. Is it because in this way, some claim, certain snakes bear their young, or because Pallas sprang that way from the head of Jupiter?[16]]

Initially, in Alciatus’ works, the above verse was topped with the Biscione crest – a serpent with a human figure in its mouth, on a shield hanging from a tree.[17] Szarffenberg substituted the image with a similar one, displaying the crest on a shield but with no background (Ill. 4). The illustration was topped with the following title: In insignia serenissimae reginae Poloniae [for the crest of her royal highness, Queen of Poland]. Thanks to this, Alciatus’ text was detached from its original context and could be reused in relation to a different person. The form used by the Cracovian printer is also fully compatible with stemmata which were popular at that time. Readers unfamiliar with the Italian lawyer’s works could not notice that what they had in front of them were modifications of an existing construction. It was probably also the character of the emblem that encouraged Szarffenberg to adapt it. In its original form, it was a panegyrical depiction of motifs present in the crest of Maximiliano Sforza. Alciatus connected the depiction of a snake and the emerging human form with the divine descent of Alexander the Great, whose mother Olympias was supposedly seduced by Amon in snake form. It is also related to the birth of Athena, who emerged from the head of Zeus, and was supposed to suggest that the Sforzas were of heroic descent and put them on the same level as ancient mythological and historical figures. This panegyrical, allegoric story was in fact compatible with what the stemmata’s authors wanted to express, so it needed no correction. This particular piece was perhaps chosen as an addition to the dedication not only because of its form, but due to the Italian provenance of both the artist and the queen. When Szarffenberg decided to use Alciatus’ emblem, he may have wished to show his patroness how well oriented he was to cultural trends and publishing novelties fashionable in her country. It should also be mentioned that the instances of “emblematic thinking” and use of allegories characteristic of these works are also visible in the preface addressed to the queen.[18] Readers may find there the topos of storks protecting elderly parents, known from Emblematum Liber (specifically, in the emblem entitled Gratiam Referendam, already present in the editio princeps – see ill. 5). But one must remember that such motifs were popular due to classical literature. The image of storks carrying elderly parents on their wings derives from a popular ancient belief that these birds form strong bonds and feel powerful love (pietas). Storks were said to be grateful for their parents’ care, according to Pliny (Historia Naturalis 10.32.63) and Elian (De natura animalium 3.23). Sources of the emblem can also be traced to Horapolla’s treaty (Hieroglyphica 1.55) and the anonymous Physiologus (8). Szarffenberg, when calling upon the image of young storks caring for their parents, could of course have based his idea on still a different source. However, his use of Emblematum Liber in his choice of stemma makes it probable that in this case also he was inspired by Alciatus. However, an important question is who inspired Maciej Szarffenberg to reach for Alciatus’ emblem. Although nobody denies his competence and familiarity with sixteenth-century literary production,[19] it seems unlikely that it was his own idea, and we must rather reckon with the fact that someone suggested it to him.[20] It is difficult, however, to indicate a specific person. Most likely it was someone from the printer’s entourage, probably a closely related, broad-minded author of wide, humanistic horizons. One potential candidate is Franciszek Mymer, who came from Silesia and studied in Cracow, and who not only was a relative of the Szarffenberg family (Marek Szarffenberg was his uncle) but also repeatedly collaborated with Maciej and edited his works in his printing house.[21] This is, however, only an unsubstantiated hypothesis. Maciej Szarffenberg did not even once print Alciatus’ set of emblems, and we can assume that he had no contact with it as a bookseller either, since the inventory of his bookstore published by Artur Benis does not note a single copy of this work.[22] Interestingly, the emblems of the Italian jurist are on the inventory drawn up after the death of Helena Unglerowa, with whom Maciej Szarffenberg competed and, as already mentioned, from whom he stole the manuscript of Farraginis actionum iuris civilis et provincialis libri by Tucholczyk annotated with the author’s own amendments.[23] However, this list was drawn up later than the events in which we are interested, in 1551. Additionally, on the basis of the relevant note contained in it, it is hard to say which reprinting of the famous emblems we are dealing with. The brief note reads simply “Emblemata Alciati exemplaria”, and could refer to either the older edition or the newer, maybe even the second book of emblems published in Venice, which included 86 new items.[24] The question of who came up with the idea of using Alciatus’ epigram in conjunction with Bona Sforza’s coat of arms therefore remains for the moment unanswered. Bona Sforza’s crest was exploited by many other Polish artists. For example, Andrzej Krzycki, who was, for a time, the queen’s personal secretary, alludes to her crest in his works. He even permitted himself to make some jokes, such as linking Sforza’s serpent with the Cracovian dragon.[25] The queen’s crest also appears in earlier stemmata. One of them, probably the earliest, was placed on the title page of Rudolf Agricola’s work entitled Illustrissimae reginae Bonae paraceleusis ad episcopum Plocensem, published by Haller in 1518.[26] The crest depicts two emblems connected with each other: the White Eagle and Biscione with a crown above them, and below a Latin distich referring to both of the emblems. It is probable that Agricola was the author of this composition, although it remained unsigned in print. Szarffenberg was thus a pioneer simply because instead of writing a new verse, he used an existing poem which fit the occasion of publication. Another issue worth pondering is the edition of Emblems used by Maciej Szarffenberg to copy the opening piece. It can be assumed with a high degree of probability that he found it in one of the three Augsburg editions (28 II 1531, 6 IV 1531, 1534), since the reading of concelebrare, which he places in the fourth line, was changed to concelebrasse in 1534.[27] This indicates that one of the three oldest versions, probably unapproved by Alciatus, appeared in Poland. From one of these Szarffenberg must have taken the epigram. Polish literary society could have come across the first selection of emblems quite quickly, right after its release. This allows us to assume that Alciatus’ compositions inspired Old Polish writers from the very beginning. Is it possible that his influence will also be visible in other stemmata from the first half of the 16th century? To determine this would require additional studies. It is, however, certain that the influence became visible in the second half of the century. Mikołaj Rej’s Źwierzyniec is a good example of this. In the fourth volume, numerous references to the art of emblems can be found.[28] Szarffenberg’s borrowing of Alciatus’ poem in praise of Bona Sforza was still one of the first instances of the reception of Emblematum Liber in Poland.

Translated by Zofia Marcinek

[1] On the subject of stemmata see F. Pilarczyk, Stemmata w drukach polskich XVI wieku, Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogicznej, Zielona Góra 1982; W. Kroll, Heraldische Dichtung bei den Slaven: mit einer Bibliographie zur Rezeption der Heraldik und Emblematik bei den Slaven (16.–18. Jahrhundert), Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1986; B. Czarski, Stemmaty w staropolskich książkach, czyli rzecz o poezji heraldycznej, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Warszawa 2012. [2] A wood engraving of Astronomy personified, along with a double verse, was used by Jan Haller in 1511: Jan of Głogów, Computus Chirometralis, expensis Johannis Haller, Cracoviae 1511, k. A1r. [3] Editio princeps: Viri clarissimi d. Andre[a]e Alciati iurisconsultis Mediol. ad d. Chonradum Peutingeru[m] Augustanum, iurisconsultum Emblemaum liber, [Augsburg] 1531. Polish translation: Andrea[s] Alciatus, Emblematum libellus. Książeczka emblematów, translation and commentaries by M. Mejor, A. Dawidziuk, B. Dziadkiewicz, and E. Kustroń-Zaniewska, ed. R. Krzywy, Warszawa 2002. See the newest edition of Alciatus’ first volume (based on editions from between 1531 and 1534): A. Alciato, Il libro degli Emblemi secondo le edizioni del 1531 e del 1534, introduzione, traducione e commentato di Mino Gabriele, Adelphi Edizioni S.P.A., Milano 2009. The rich commentaries accompanying each piece should be considered this edition’s greatest assets. [4] For references on Alciatus’ life, see R. Abbondanza, Alciato (Alciati), Andrea, [in:] Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 2 (1960), http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/andrea-alciato_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ [available: 06.09.2016]. [5] A list of editions of the Emblematum liber has been published in H. Green, Andrea Alciati and His Book of Emblems: A Biographical and Bibliographical Study, London 1872; cf. M. Praz, Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery, Roma 1964, p. 248–252. The authorised editions are also discussed by J. Pelc in his Emblematy, książki emblematyczne. Problemy teorii a praktyka twórców, “Barok. Historia-Literatura-Sztuka” vol. 3 (1996), p. 38–39. [6] Alciatus’ emblems were considered by Robert Cummings to be a collection of rarities (Alciato’s “Emblemata” as an Imaginary Museum, “Emblematica” vol. 10, nr 2 (Winter 1996), p. 245–281). [7] See B. F. Scholz, The 1531 August Edition of Alciato’s “Emblemata”: A Survey of Research, “Emblematica. An Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies” vol. 5 (1991), p. 214–254. [8] It is important to mention that this piece was first published in printed form on 28th February 1531 and that the addressee of the emblem died on 4th July 1530; he lost power in the author’s country even earlier, since he was in French captivity from 1515. Beginning the volume with an emblem dedicated to a prince who was no longer ruling may have been an expression of the author’s political beliefs, or a praise of his country and longing for the days when all power was in the hands of the local aristocracy. [9] See J. Pannonius, Joannis Pannonii episcopi Quinque ecclesiarum, poetae et oratoris clarissimi Panegyricus in laudem Baptistae Guarini Veronensis praeceptoris sui conditus, in aedibus Hieronymi Vietoris et Ioannis Singrenii, (Viennae Austriae 1512), p. e4v. We know that some copies of this book were meant for the Polish market because of a stemma placed at their end, accompanied by the crest of the Polish Kingdom and entitled Aquila loquitur. Wietor used the same poem after he moved to Cracow: J. L. Decjusz, Diarii et earvm qvae memoratu digna in splendidissimis potentiss. Sigismvndi Poloniae Regis et [...] Bonae Mediolani Bariq[ue] ducis principis Rossani nuptiis gesta […] descriptio, per Hieronymum Vietorem, Impressum Graccouiae 1518, p. H6v. [10] See . J. Łaski [Johannes a Lasco], Oratio ad Leonem X in obedientia nomine Sigismundi regis Poloniae [...] habita 13 Iunii 1513, apud Florianum Unglerium, [Cracow] 1513, p. A1r. [11] See A. Krzycki, Ad Divvm Sigismvndvm Polonie Regem Et Magnvm Dvcem Lithvanie Semper Invictvm Post Partam De Moskis victoriam Andree Krziczki inclite co[n]iugis sue Ca[n]cellarij Carme[n], in aedibus Ioannis Haller, Cracovie 1515, p. A1r. [12] J. Tucholczyk, Farraginis actionum iuris civilis et provincialis Saxonici municipalisque Maydeburgensis libri septem […], per Mathiam Scharffenberg, Cracouiae [post 3 VII] 1542. [13] See Drukarze…, p. 241–242, 315–316. Unglerowa edited Farrago a year after Szarffenberg: J. Cervus, Farraginis actionvm ivris ciuilis et prouincialis Saxonici […], excusum in officina Vngleriana, Cracouiae [post III] 1540. [14] See ibidem, p. 250–251. [15] A. Alciatus, Emblematum liber, per Heynricum Steynerum, excusum Augustae Vindelicorum 28 II 1531, k. A2v. The spelling has been corrected in accordance with the Polish-Latin dictionary edited by M. Plezia (Warsaw 1998–1999). The punctuation has also been modified to fit the rules current in Polish. All abbreviations and ligatures have been removed with no additional indicators. [16] Translation by www.mun.ca/alciato (accessed: 18.12.2006) [17] The Sforzas took their crest from the family of Vischonti who ruled in Milano until 1447. The first Sforza to rule in Milan was Francisco I, married to Bianca Maria, daughter of Philippo Maria, the last Vischonti duke. By using the same crest, the Sforzas wanted to stress the continuity of power. [18] J. Tucholczyk, op. cit., p. A2r–A3r. [19] J. Krauze-Karpińska, Polscy drukarze wieku XVI a filologia humanistyczna, [w:] Humanizm i filologia, redakcja naukowa A. Karpiński, Wydawnictwo Nerition, Warszawa 2011, p. 185–186. [20] For the excitation of doubt in this matter I would like to thank very much Professor Paulina Buchwald-Pelcowa. [21] See e.g. Polski słownik biograficzny, t. XXII, Wrocław 1977, p. 357–358; B. Sajna, Mymer's Dictionarius... and Cotenius’ Vocabulary...: Unique Editions of Much-Read Books in the Early Printed Books Collection of The National Library, „Polish Libraries” vol. 2, 2014, p. 220–233. [22] Materiały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, wydał A. Benis, w Drukrni „Czasu” Fr. Kluczyckiego i Spółki pod zarządem Józefa Łakocińskiego, Kraków 1890, p. 6–36. [23] Ibidem, p. 43, no. 1084. [24] A. Alciato, Andreae Alciati Emblematum libellus, nuper in lucem editus, (apud Aldi filios), Venetiis 1546. [25] Andreae Cricii Carmina, ed. K. Morawski, Academia Litterarum Cracoviensis, Cracoviae 1888, p. 87. [26] R. Agrykola, Illustrissimae reginae Bonae paraceleusis ad episcopum Plocensem, Jan Haller, [Cracow 1518], k. [1]r. [27] A. Alciatus, Emblematum libellus, excudebat Christianus Wechelus, Parisiis 1534. [28] I. Chrzanowski, „Zwierzyniec” Mikołaja Reja z Nagłowic, “Ateneum” 1893, vol. 3, p. 288˗289; J. Pelc, Rola emblematów oraz konstrukcji im pokrewnych w twórczości Mikołaja Reja, “Pamiętnik Literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej”, vol. 60, nr 4 (1969), p. 65–101. |

Ill. 1. Alciatus, Emblematum liber, per Heynricum Steynerum, excusum Augustae Vindelicorum 28 II 1531, p. A1r (Title-page of the first edition of Emblematum Liber).

|