ANNA KOŁOS

SOME REMARKS ON THE ICONOGRAPHY OF EMBLEMATIC EXHORTATIONS IN THE “PERISTROMATA REGUM” COLLECTION BY ANDRZEJ MAKSYMILIAN FREDRO

|

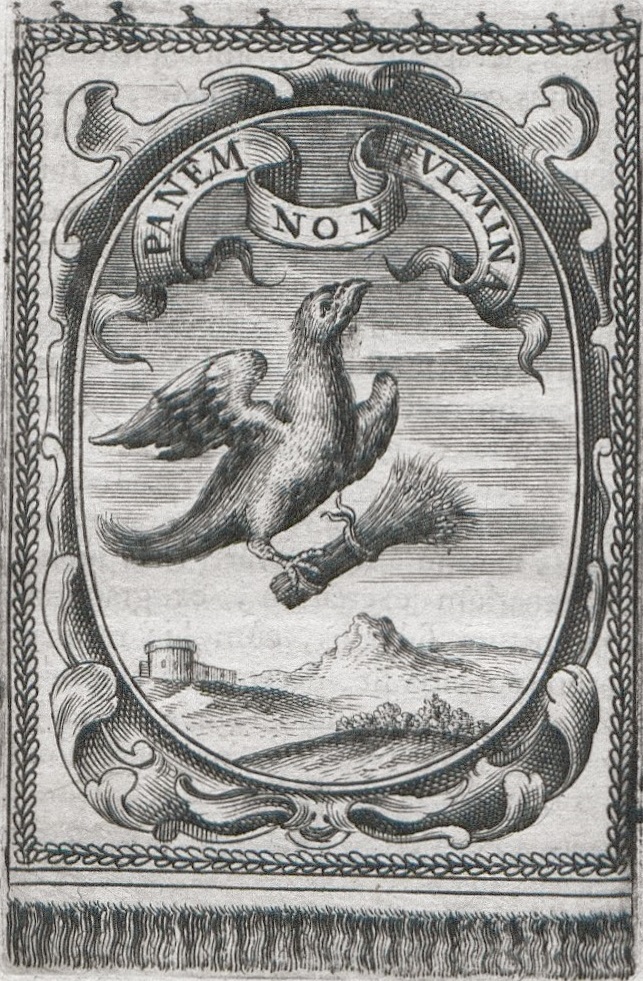

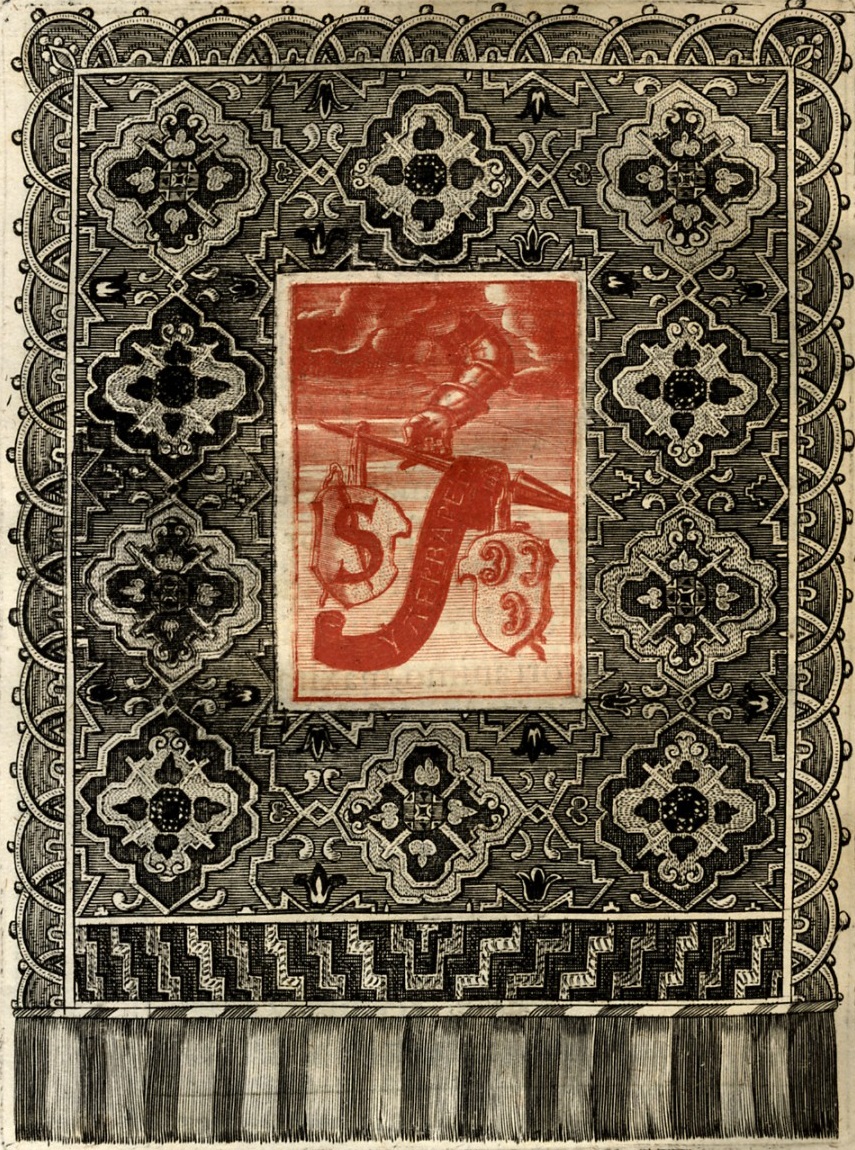

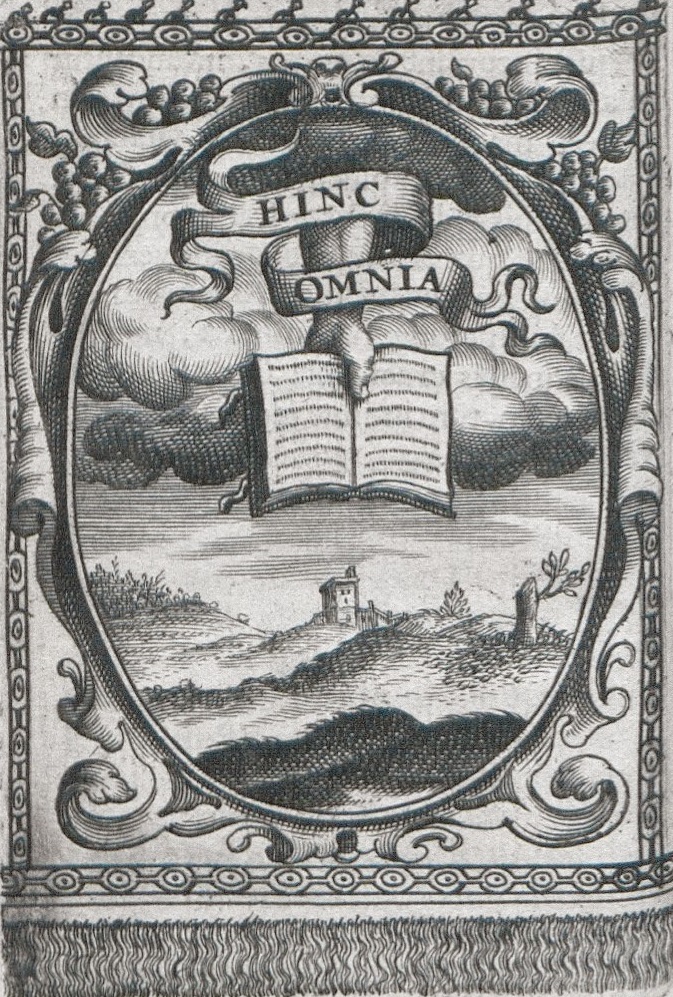

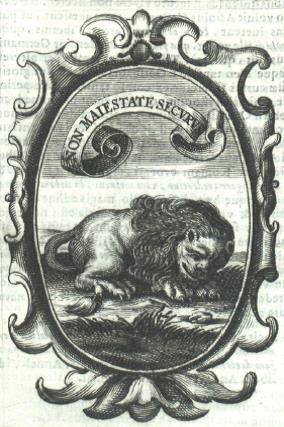

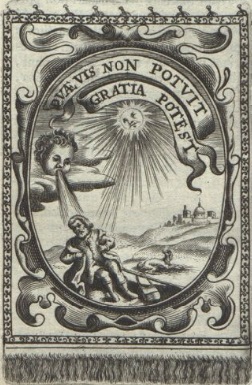

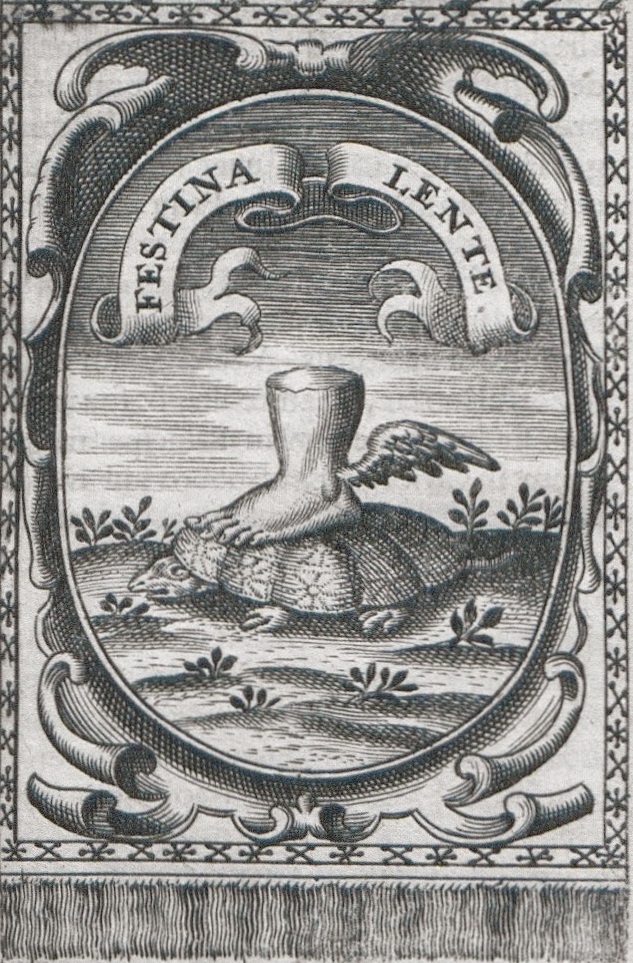

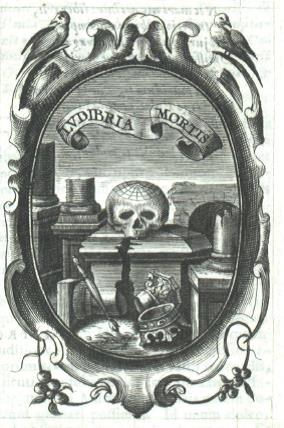

Published in 1660 in Jerzy Forster’s publishing house[1] in Gdańsk as part of the volume Scriptorum seu togae et belli notationum fragmenta, the collection of twenty copper prose engravings by Andrzej Maksymilian Fredro known as Peristromata regum, seu memorial principis monitorum symbolis expressum was rightly ranked by Janusz Pelc among the most interesting compositions of 17th-century Poland.[2] Despite this praise, the cycle has not yet been analysed in depth.[3] This article is an attempt to signal several issues of iconography and composition which deserve broader attention. The issue of nomenclature seems to be the most important: the title is closely related to the form of the cycle. In the paratext, Fredro used the rare Greek term peristroma,[4] which means a ‘carpet’, ‘tapestry’ or ‘bed covers’. In the preface, the writer, who is fluent in the art of compiling, describes his work as a supplement to the collection Scriptorum Fragmenta, thus making it a selection from his earlier works.[5] The main source upon which Fredro drew in the creation of the cycle seems to have been “non-literary” emblematics,[6] decorations in private and public space (royal apartments) which, while pleasing to the eye, are also morally didactic. Remaining in accord with the accustomed function of an emblem (delectare et docere), Fredro explains the singular form of Peristromata as a literary counterpart to the imagery that could potentially decorate the walls of a royal palace. In the emblematic tradition before Fredro there is one piece that is well known: a rather slim volume entitled Peristromata turcica, sive dissertation emblematica.[7] It is a Latin translation of an anonymous French print published in 1641 in Nuremberg. One year later a replica was published, Aulaea Romana.[8] In place of the Greek lexeme, it proposes the Latin word “aulaeum”. In addition to those on its title page, Peristromata Turcica contains six colourful emblems placed on an ornamental tapestry adorned with decorative tassels at the bottom. In the centre are several small fields consisting of allegorical scenes and Greek lemmas (ill. 2). Engravings from this edition, which was probably known all around the country, especially in Gdańsk,[9] can be described as the closest in terms of artistic form to the ones from Fredro’s collection.[10] Their author is unknown.[11] Just as in the case of the Nuremberg print, the Polish emblems are clearly intended to imitate the look of a decorative tapestry – in addition to the tassels they depict, in the top part of the engraving, the nail heads which would be used to hang the tapestry (ill. 3). The icon itself takes on the form of an allegorical image in a vertical oval framed by a cartouche with a scroll.[12] The cartouche, on the other hand, is written into a square framed like a decorative carpet. The composition in general is highly coherent. Each icon in the top part of the oval field consists of a decorative flag with a Latin lemma. Only the border changes. In comparison to German prints, the framing of Polish tapestries seems ascetic. The ornaments do not obscure the main allegory, which dominates the decorations by means of its size. An artistic analysis of the imago itself indicates resemblance to engravings from a collection of emblems which became famous in Poland: the Spanish Idea de un principe politico Cristiano by Diego de Saavedra Fajardo (ill. 4), published in 1640 in Munich.[13] Fredro greatly respects Saavedra and calls him “Nobilis scriptor Hispanus”.[14] Among multiple similarities between the two writers we could enumerate a moralising attitude, didacticism, an attempt to a pragmatic comments upon the power theories when traditional Christian-Ciceronian ethics experiences a crisis, closeness to Justus Lipsius political reflections, scepticism towards the psychology of both an individual and a group and finally, adding gravity to dissimulations.[15] In terms of writers’ practice, both authors adorned their speculorum principum emblems with commentaries in the form of essays. This method was compatible with the character of their works as a noble otium crafted in moments of peace between fulfilling their political duties.[16] Fredro’s iconography is highly diversified and unique. His didactic recommendations are generally theoretical, which makes it possible for him to get rid almost entirely of the catalogue of most popular and prolific personifications of virtues or static allegories of non-material values. It is interesting how much stress is put on setting the scenes against the background of natural sceneries; this is contrary to older related prints, such as Typotius’ Emblemata, which use an abstract background. The artist uses the fixed motif of manus Dei, a hand emerging from the clouds. This, just as in Saavedra’s piece, allows him to introduce allegorical forms (Peristroma I, II, III, VIII, and XIV). Another important aspect is the role of parabolic scenes with animal symbols (Peristroma VII and XII), which can be considered part of a common tendency to draw comparisons between politics and the animal world. It works especially in the context of artis dissimulandi. In the tapestries mentioned the author unambiguously characterises animal behaviours that should also be followed by rulers. Secrecy is a feature represented by an owl, hunting in the dead of night (secreto videt); silence (taciturnitas),[17] emotional continence and apparent apathy are pictured by a fox who “lies as if he were dead and easily catches birds”.[18] Saavedra uses similar measures. Writing of dissimulation, he calls upon the image of a serpent, and a lion who sleeps with his eyes open (vigilantia).[19] In Fredro’s work, the owl is distantly related to a picture from Pierio Valeriano’s Hieroglyphica (1556) – a night heron symbolises a tyrant. It is significant that Fredro, while advising a ruler to be deceitful, makes the image morally unambiguous, as it would not have been in the 16th century.[20] Also within the representation of natural world is the 15th emblem (vescitur paleis). It depicts a horse tied to a wooden pole and is closer to a genre scene than to an allegory. The same could be said about the 18th tapestry (Altum crescent caeterum steriles). The image depicts seven slender trees which only become an allegory for vain greatness without virtue when a commentary is added. Emblem number 4 is especially interesting, given the background of iconographic erudition of the cycle’s creators. Entitled Quae vis non potuit gratia potest (Ill. 5), it is in fact an illustration of Aesop’s fable about the North Wind and the Sun. The moral of the story blends very well with the notion of the strength and efficacy of a gift, expressed in the emblems Panem non fulmina (5) and Dando accipit (8). Among the rich exemplary materials gathered by Fredro in his moral writing, references to fables are quite rare. Sun and wind being animalised in the emblem’s icon[21] also stands out in the context of Peristromata. As was said in Krzysztof Niemirycz’s fable written at the end of the 17th century, “Quiet strength reaches the heart sooner than loud”.[22] Fredro, on the other hand, summarised this message in an aphorism: “Sic gratia profecit quantum vis non potuisset”,[23] advising the ruler to act similarly towards his subjects, treating them “more like sons than like slaves”.[24] Festina lente (Ill. 6) is the only emblem referring to the most important and prolific watchwords. In its icon we can see a winged foot standing on top of a turtle’s shell. This causes a visual contamination of various symbolic images. Next to identifying a gnome with Aldus’ printer’s signature, the turtle became one of the most common carriers of meaning. In Cosimo de Medici’s emblem we can see a spread sail on the turtle’s back.[25] It is similar to the image shown by Peter Isselburg and Georg Rem in their print Emblemata politica (Nuremberg, 1617).[26] The Hypnerotomachia on the other hand is the source of the image of a woman holding wings in one of her hands, and a turtle in the other.[27] The variation made by Fredro seems to connect to famous visual traditions, conceptualising the motif of wings together with a foot resembling classical depictions of Mercury. Peristroma 16 (Quae ad naturam non nocent), displaying a burning salamander, refers to concepts from Classical natural history,[28] which states that this reptile is capable of devouring fire, while ostriches eat iron.[29] A salamander in flames, together with a royal crown and a Nutrisco et extinguo lemma, became a watchword for Francisco I; the version without royal attributes was included in Typotius’ collection as an icon inscribed Durabo and Mi nutrisco.[30] For Fredro, the salamander became an embodiment of the thesis that harmony exists between nature and humanity, calling for respect for different habits on the socio-political plane. It also makes the notion of natural law, broadly discussed in the 17th century, part of the author’s conservative understanding of the authority of tradition, especially in connection with noble liberty. In the 19th emblem, entitled Nihil tam firmum est cui periculum non sit etiam ab invalido, Fredro uses a common hieroglyphic sign, an elephant, but with no reference to the repertoire of virtues[31] this animal used to symbolise. Instead he provides a description from the writings of a historian, Curtius Ruphus. The relation between the picture and lemma is based on contrast and depicts a thought crucial for Fredro – of power’s vanity and fragility – since “even elephants fear mice”.[32] Among other motifs depicted in Fredro’s cycle a special place should be granted to an independent architectural motif: caesura nisi cohaerentia, a stone-clad vault symbolising “consent between citizens”.[33] It is thus a group composition in which the people hold up the royal crown (his fulcris potens). Another separate element is Peristroma 6 (Non omnibus) which depicts a curtain drawn in an interior with precisely drawn architectural details (columns adorned with acanthus holding up a vault with an oculus), referring to Solomon’s temple.[34] In his commentary, the author expresses his certainty about the necessity of upholding the king’s majesty by his seclusion and indifference, again displaying his sociotechnical sense. Finally we should pay some attention to the emblem which concludes the volume, tandem haec facies maiestatis cedendum successori,[35] which refers to the futility of life (a skull next to royal attributes and an empty throne). In his moralising attempts Fredro does not reach for pedagogics of fear or appeal to life’s vanity. But in Peristroma 20 (ill. 7) he does use the attractive motif of death which concludes the topic of pondering on good Christian rulers, praising those who are remembered by their descendants. It is here that another similarity to Saavedro can be found: he terminated his cycle with an image of a grave with royal attributes (Futurum indicat).[36] His work ends with a reflection on the ruler’s place in his subjects’ memory. In an epilogue to the Spanish author’s cycle there is also an emblem signifying vanity: Ludibria mortis (ill. 8), adorned with a poetic subscription.[37] Fredro in his iconography uses motifs from the epilogue – but he adds a reflection which draws closer to Saavedro’s last essay, praising the good death and honoured memory of the ruler. Against the background of Fredro’s moral and political writings, Peristromata is an example of his closeness to Saavedro’s ideas. He was, however, also familiar with Lipsius’ works, a writer who believed that, contrary to Plato’s ideas, “we live among people who seem to be made of nothing but greed, deception and lies”.[38] Fredro does not present simplistic ideas of moral perfection that would be in accord with the contemporary ideas of rulers’ virtuousness. He believed firmly in people’s weakness (fragilitas humana), and did not even spare the king.[39] The pragmatic aspect of his reflections makes his work unique: he does not satisfy himself with standard conventions on either the intellectual or the visual tier. Instead Fredro strives to broaden the fields of meaning for the symbols he uses, in order to fulfil his ever-present didactic intention.

Translated by Zofia Marcinek

[1] A.M. Fredro, Peristromata regum, [in:] Scriptorum seu togae et belli notationum fragmenta; accesserunt Peristromata regum symbolis expressa, sumptibus Georgii Försteri, Dantisci 1660, p. 305–381. The subsequent edition, with a different graphic layout, was published in 1685 in Frankfurt. All quotations are after the modern critical edition: A.M. Fredro, Scriptorum seu togae et belli notationum fragmenta. Accesserunt “Peristromata regum symbolis expressa”. Fragmenty pism, czyli uwagi o wojnie i pokoju. Zawierają dodatkowo „Królewskie kobierce symbolicznie odtworzone”, tr. J. Chmielewska, B. Bednarek, foreword M. Tracz-Tryniecki, Narodowe Centrum Kultury, Warszawa 2015 [2] J. Pelc, Słowo i obraz na pograniczu literatury i sztuk plastycznych, Universitas, Kraków 2002, p. 252. [3] For the most important editions, see p. 252–259; Z. Rynduch, Andrzej Maksymilian Fredro (portret literacki), Gdańskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, Gdańsk 1980, p. 111–121; U. Olbromska, Kobierce, czyli ilustracje do „Peristromata regum symbolis expressa” A. M. Fredry, “Galicja” 2000, vol 1, p. 37–43. [4] In the representative function of a particular designate, the word was used by Roman authors such as Plautus or Cicero. As a literary term it appears in the 17th century, for the first time in the title of the Peristromata sanctorum collecta collection of Arnold de Raisse (1630). [5] See A. M. Fredro, Peristromata regum, [in:] Scriptorum fragmenta, p. 655. [6] This is especially the case in the description of Panem non fulmina (5), depicting an eagle with a bundle of grain in his talons (the blazonry of the Waza family), bringing bread instead of thunder – this image was originally supposed to adorn the chamber of Władysław IV. The author treats this as an exemplum in his preface and then develops it in Peristroma 5 (ill. 1). In the tenth emblem (his fulcris potens) he refers to the famous “Wawel heads” adorning the ceiling of the Parliament chamber. [7] Peristromata Turcica, sive dissertatio emblematica, praesentem Europae statum ingeniosis coloribus repraesentans, [Wolfgang Endter, Nürnberg 1641]. On the title page there is no indication of where and in which house the piece was published; the date is encrypted within a chronogram. The colophon contains information on the French edition: “Lutetiae Parisiorum primum apud Toussaint du Bray, in platea P. Jacobi ad insigne Spicae”. [8] [G.P. Harsdörffer], Aulaea romana contra Peristromata turcica expansa, sive dissertatio emblematica concordiae christianae omen repraesentans, [Wolfgang Endter, Nürnberg 1642]. [9] See J. Pelc, op. cit., p. 255 [10] In the Aulaea romana pamphlet the artistic idea for the emblems was changed: the authors eliminated the elements directly resembling carpets or tapestries; the only possible remaining example is Peristromata turcica. [11] The suggestion has been made that differences in spelling point towards there being more than one author (U. Olbromska, op. cit., p. 43). [12] The first emblem has motifs of fruits written into the retracting cartouche element. [13] Saavedro’s authority was called upon by Fredro (Scriptorum fragmenta, Monita) and Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski (Rozmowy Artaksesa i Ewandra). In the Cistercian abbey in Sulejów, probably before 1686, someone created a decoration for the church organs which used four emblems of the Spanish artist (see P. Rosiński, Obrazy emblematyczne w kościele Cystersów w Sulejowie, “Kieleckie Studia Teologiczne” 2002, vol 1–2, p. 413–425). Similarities have been noted by Paulina Buchwald-Pelcowa (Emblematy w drukach polskich i Polski dotyczących XVI–XVIII wieku. Bibliografia, IBL PAN, Ossolineum, Wrocław, Warszawa 1981, p. 39). Saavedro’s works were reissued many times in Spanish, and between 1649 and 1659 were also issued in Latin in Brussels, Köln and Amsterdam. It is possible that Fredro used one of these. The closest probable model for Saavedro is Emblemata politica by Jacob Bruck Angermundt, published in Köln and Strasbourg in 1618. See F. J. Díez de Revenga, Introducción, [in:] D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Empresas políticas, edición, introducción y notas de F.J. Díez de Revenga, Planeta, Barcelona 1998, p. XL; R. Bireley, The Counter-Reformation Prince. Anti-Machiavellianism or Catholic Statecraft in Early Modern Europe, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1990, p. 194. [14] A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 640. [15] See M. Tracz-Tryniecki, Wstęp, [in:] A.M. Fredro, Scriptorum fragmenta, p. 52–53. [16] Both authors mention this issue: A. M. Fredro, Librorum legendorum ratio, [in:] Scriptorum fragmenta, p. 647; D. de Saavedra Fajardo, op. cit., p. 7–8. [17] Taciturnitas is for Fredro, just as it is for Saavedro, an important issue to reflect upon. He returns to it in his Monito as well. In the 12th emblem (Non auceps nisi dormiat) Fredro says “Taciturnitas etiam est pars dissimulatonis, imo ipsa Mater” (A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 730). Saavedro on the other hand claims silence is the ruler’s most important tool (D. de Saavedra Fajardo, op. cit., p. 278). [18] A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 731. [19] The issue of dissimulation is best described by Saavedro in emblems 43 (Ut sciat regnare), 44 (Nec a quo nec ad quem), and 45 (Non maiestate securus). See D. de Saavedra Fajardo, op. cit., p. 274–289. [20] As Valeriano wrote, “Huius quodammodo generis est Nycticorax, qui tyrannidem significat, ob occultationem scilicet consiliorum, quae dissimulare potentiores pro magno habent negotio” (P. Valeriano, Hieroglyphica, sive de sacris Aegyptiorum literis commentarii, [Michael Isengrin], Basileae 1556, p. 148: XX, Tyrannus). The author mentions a night heron, but the subsection is in the section entitled De noctua, and is accompanied by a drawing which definitely depicts an owl. [21] This is similar to illustrations of fables such as Cento favole morali by Giovanni Mario Vendizotti, reissued many times since 1570. [22] K. Niemirycz, Wiatr i Słońce, [in:] Antologia bajki polskiej, selected and edited by W. Woźnowski, Ossolineum, Wrocław 1982, p. 170 (v. 39–40). [23] A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 676. [24] Ibidem, p. 677. [25] H. B. Werness, The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in World Art, Continuum, New York, London 2006, p. 416. [26] See M. Praz, Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery, Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, Roma 1964, p. 381. [27] See J. Pelc, op. cit., p. 258. [28] The main point of reference is Pliny’s Natural History. See “Salamandra sive alitur igne, sive extinguit ignem, ut Plinius tradit…” (J. Typotius, Symbola divina et humana pontificum, imperatorum, regum. Accessit brevis et facilis isagoge. Tomus primus, Pragae 1601, p. 66: Hierographia regum christianorum, XXI). [29] A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 755. [30] J. Typotius, op. cit., p. 37 (Regum francorum…, XXIV), p. 66 (Hierographia regum christianorum, XXI). [31] In Valeriano’s works the elephant is a symbol of (among other things): goodness (pietas), justice (aequitas), munificence (munificentia), and moderation (temperantia). See P. Valeriano, op. cit., p. 14–20. [32] A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 781. [33] Ibidem, p. 737. [34] Ibidem, p. 689. [35] We may also notice a slight departure from the customary convention of placing bands with Latin lemmas in the top part of the depiction. Peristroma 20 is the only one in the collection to feature a band surrounding the entire icon. [36]A. M. Fredro, op. cit., p. 781. [37] Ibidem, p. 683. [38] J. Lipsius, Politica Pańskie, to jest, Nauka jako pan i każdy przełożony rządnie żyć i sprawować się ma, nie tylko panom pożyteczna, ale i nie panom ucieszna…, ed. Paweł Szczerbic, w Drukarni Łazarzowey, Kraków 1595, p. 123. [39] A. M. Fredro, Peristromata regum, p. 691. |

Ill. 1. Peristroma V (Regnum Poloniae) [in:] Peristromata turcica, sive dissertatio emblematica, praesentem Europae statum ingeniosis coloribus repraesentans, [Wolfgang Endter, Nürnberg 1641], p. D3v.

Ill. 3. D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Symbolum XLV (Non maiestate secures), [in:] idem, Idea principis christiano-politici, 101 siimbolis espressa, apud Iacobum van Meurs, Amstelodami 1651, p. 340.

Ill. 4. D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Symbolum XLV (Non maiestate secures), [in:] Idea principis christiano-politici, 101 sijmbolis espressa, Apud Iacobum van Meurs, Amstelodami 1651, p. 340.

Ill. 6. A. M. Fredro, Peristroma XVII (Festina lente), [in:] idem, Scriptorum fragmenta…, p. 370.

Ill. 8. D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Ludibria mortis, [in:] idem, Idea principis christiano-politici…, p. 831.

|