WALTER KROLL

STEFAN JAWORSKI AND EMBLEMATICS

|

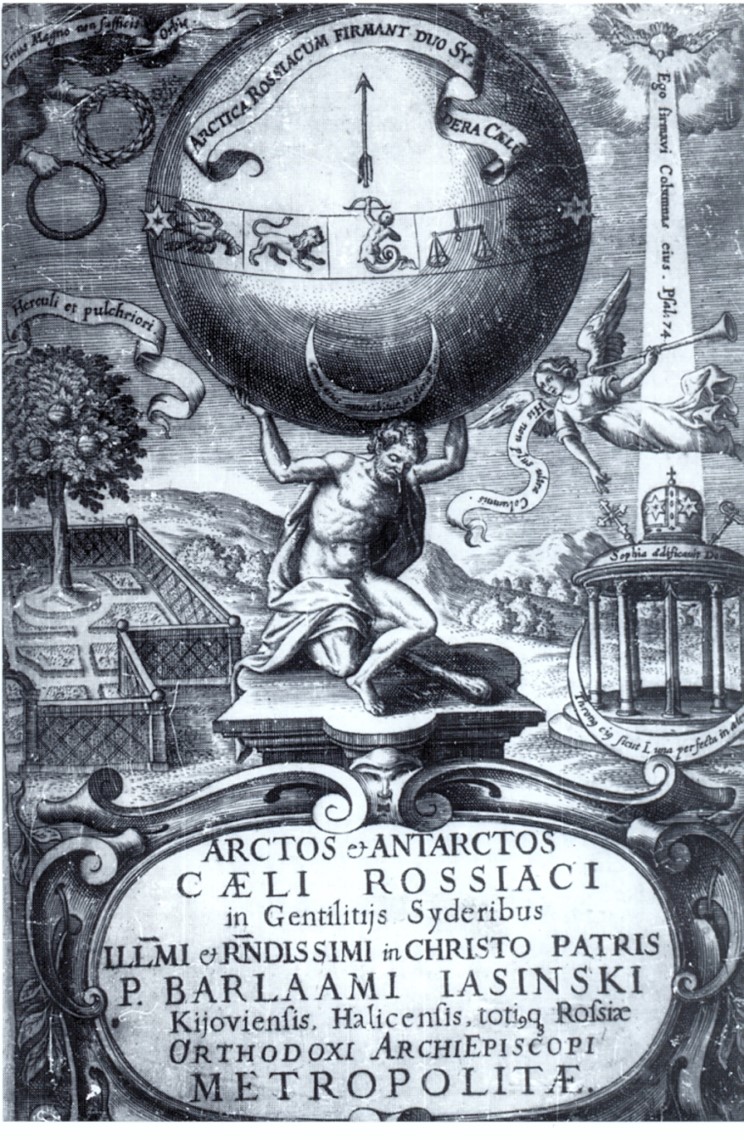

Stefan Jaworski (1658–1722) is one of the „unknown”[1] Polish-speaking poets of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy’s trilingual milieu in the era of Baroque. Russian, Ukrainian and German readers consider him primarily as a bishop – metropolitan of Ryazan, preacher and theologian. However, the context of Orthodox Christianity masks the Polish implications of his works, stemming from his education. Having graduated from the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in the year (circa) 1684, he attended Jesuit colleges in Lviv, Lublin, Poznan and the Academy of Vilnius. In these schools, Jaworski perfected his knowledge of Polish and Latin, also extending his competencies in rhetoric, poetics, philosophy, theology and homiletics. After his return to Kyiv, where was awarded the title of poet laureate (лавроносный пиит)[2], Jaworski gave rhetoric, and later philosophy and theology lectures at the College in the years 1690-1700. In 1700, Tsar Peter the Great appointed Stefan Jaworski metropolitan of the Ryazan-Murom eparchy. In his library (whose precise description he created shortly before his death in 1721[3]), Jaworski housed over 600 volumes from different fields of science and literature, including a number of emblem books: (1) Diego de Fajardo Saavedra, Idea de un principe politico christiana (Amstelodami 1659); (2) Hermann Hugo, Pia desideria (Antverpiae 1624); (3) Otto Vaenius, Amorum emblemata (Antverpiae 1612); (4) Jeremias Drexel, Zodiacus christianus (München 1618); (5) Maximilian Sandaeus, Maria Flos Mysticus (Moguntiae 1629); (6) Henricus Engelgrave, Lux Evangelica sub velum Sacrorum Emblematum Recondita (Antverpiae 1648); (7) Henricus Engelgrave, Caeleste pantheon, sive caelum novum, in festa et gesta sanctorum totius anni morali doctrina, ac profana historia varie illustratum (Coloniae Agrippinae 1671); (8) Sebastian a Matre Dei, Firmamentum Symbolicum (Lublini 1652); (9) Andrzej Młodzianowski, Icones symbolicae (Vilnae 1675); (10) Ioannes Michael von der Ketten, Appelles symbolicus (Amstelaedami et Gedani 1699); (11) Daniel de la Feuille, Devises et emblèmes (Amsterdam 1691); (12) Symbola et Emblemata selecta (Amsterdam 1705). Moreover, Jaworski and his engraver Szczyrski had at their disposal the collections of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy library and the libraries of Kyivan writers such as Połocki and Prokopowicz, containing the entire canon of West European emblem books and a number of Polish heraldic compendia (Szymon Okolski, Orbis Polonus, 1641; Bartosz Paprocki, Panosza, 1575; Herby rycerstwa polskiego, 1584; Wacław Potocki, Poczet herbów, 1696). This is confirmed by the research of Dmytr Czyżewski (1894–1977) on the reception of emblematics in Ukraine in the era of Baroque[4], which was pioneering, although long-ignored in the Soviet Union. Jaworski created his Polish-language works in the period of 1684–1691, that is, at the close of the era of Baroque, when the reception of emblematics in the Kyiv-Chernihiv-Lviv region was still extensive and prolific. At that time, Jaworski authored four panegyrics[5]. The first two were not accompanied by engravings and therefore are not pictorial-verbal combinations strictly speaking: Hercules post Atlantem infracto virtutum robore honorarium pondus sustinens (Chernihiv, in the Swieto-Trojecka Ilinska printing house, [ca. 1684]) as well as Arctos et antarctos caeli Rossiaci in gentilibus syderibus [...] Barlaami Jasinski Kijoviensis Haliciensis totigq. Rossiae orthodoxi archiepiscopi metropolitae (Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv 1690). Except for its title page and the stemmat of Jasinski’s coat of arms, Arctos… is devoid of any pictorial components. The artful engraving of the title page depicts Atlas holding up the firmament (coelum Rossiacum) on which the engraver (Leontij Tarasiewicz)[6] has placed the Zodiac, Jasinski’s coat of arms and some inscriptions on ribbons. The image of Atlas was likely modeled on an icon from an emblem book by Jesuit Silvester Pietrosancta. Here, Jaworski refers to the subject of mythology from his first piece (Herkules post Atlantem), treating it in cosmic dimensions: the arrow from the coat of arms points north, to the pole star (arctos – the Great Bear); in Greek, antarctos means “opposite the bear”, thus the name of Antarctica. The author uses his key word arctos in order to set in motion the symbolism of light and brightness (jasność), from which he etymologically derives the name Jasinski. Among the plethora of quotations from and allusions to the Bible and classical literature (such as Metamorphoses by Ovid) – proofs of the intertextual quality of the work – it is easy to miss a passage from a book of songs (Lyricorum libri IV, book IV, ode 13) by Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski, to whom Jaworski refers using the antonomasia “Horacjusz Sarmacki”[7]. These data show that Jaworski was familiar not only with Sarbiewski’s treatise on the point and the joke, but also his new Latin poetry.

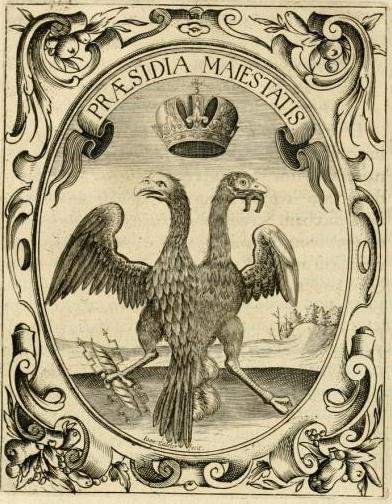

The Echo of a Voice The Ukrainian reception of emblematics (and heraldincs) is evidenced by two panegyrics devoted to Ivan Mazepa and Barlaam Jasinski, who was Jaworski’s teacher and mentor. The works demonstrate two models of Jaworski’s emblematic practice. Let us turn our attention to the first model: Echo głosu wołającego na puszczy od serdecznej refleksyj pochodzące a przy solennym powinszowaniu [...] Ianowi Mazepie hetmanowi wojsk [...] zaporoskich brzmiące głośną [...] rezonansyją (The Echo of a Voice of One Calling in the Wilderness, Coming From Heartfelt Reflection and Accompanied by Solemn Felicitation, Sounding with a Loud Resonance, to Ian Mazepa, Hetman of the Zaporizhian Host) (Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv 1689). The title alludes to the words of John the Baptist from Matthew 3:1-3, which invoke the preparation for the work of Jesus. The piece is composed of three parts: exordium – with a foreword to Ivan Mazepa in Polish, narratio – Polish poems to an escutcheon, which is constructed out the coats of arms of Mazepa’s and related families. The Mazepa coat of arms (called Kurcz) is placed in the center of the stemmat with a subscription underneath: Piękna jak jasny księżyc, jest Panna Przeczysta, (Beautiful as the bright moon is the Maiden Purest, / As she is called in Scripture by her panegyrist, / While Saint John beautifully serves as Aurora, / As he marshals for the eternal Sun of Truth. / They stand here at the Cross – for what cause? / No wonder: ‘tis where the Maiden and John have long stood.) The poem, written in Polish alexandrines, refers only to the Mazepa coat of arms (in the center: an image of a Y-shaped cross, a half-moon on the left-hand side and a six-pointed star on the right-hand side). It is not a (heraldic) description of the coat of arms, but rather its allegorical interpretation, in which the author excludes the literal sense (sensus litteralis) and instead enters the level of the allegorical (sensus allegoricus) and the moral (sensus moralis). He achieves through figural equivalences (personificatins): the moon – the Purest Maiden, and the Aurora (the star) – John (Mazepa). In this sense, the author explains the coats of arms surrounding that of Mazepa, belonging to the related families of Jasieńczyk (Key), Sas, Korczak and Odrowąż. Heraldic signs serve the author as a source of surprising concepts, associations, antytheses and comparisons[8]. The piece concludes with an eight-page elogium in Latin entitled Anacephalaiosis. The main (and the most interesting) part of the narratio are pictorial-verbal combinations, constructed out of heraldic and emblematic signs (picturae), accompanied by inscriptions. With a verbal component added, that of subscription in various forms of Polish verse and meter, they belong to the category of three-element emblems, a total of six on twenty-six pages. The rules of Jaworski’s emblematic practice in that work could be explained using two examples from the main part of the piece. The first emblem (ill. 3) shows an image of the eagle from the coat of arms of the Russian Tsardom, combined with the heraldic signs of Mazepa, held by the bird in its talons. The inspiration for this construction was emblem 22 from the collection of Saavedra[9], where a two-headed eagle holds a thunderbolt (ill. 4). Jaworski (and his engraver Szczyrski)[10] did not retain the inscription from Saavedra’s emblem, but formulated two of their own, placing them on ribbons in the eagle’s talons: to the left Suis caelum hoc illustre Planetis (“These are the glorious heavens for your Planets”), to the right Hoc fulmen in hostes („This is a thunderbolt against enemies”). In addition, the author set a third inscription under the emblem’s icon: Dum Tua Syderis sunt stemmata clare Planetis / Inde Tuam coelum quis negat esse Domum („So long as your stemmata gleam with celestial planets / Who could deny that the heavens are your Home”). The three-part structure of the emblem is secured by a subscription, written in hendecasyllable in thirty-four Sapphic stanzas, praising the acts of war and knightly-patriotic virtues of hetman Mazepa. For illustration, I present two stanzas: Niech kto chce, złoty wiek Saturna chwali, Chwal kto chcesz Pokój, ja zaś krwawe fale, (Let he who will praise the golden age of Saturn, / I – the iron age, cast from solid steel,/ I think it of far heavier weight / than golden Tags. Praise whoever will Peace, me – waves of blood, / Of the battling Bellona, if I lay them on the scale, / I see a far higher value of battle / than peace.) The engraving of the second emblem depicts Ivan Mazepa in knightly robes, riding a carriage drawn by two lions (ill. 5). The graphic model for this emblem was the visual topos of the triumphant carriage (currus triumphalis), which can be found in many emblem books. The prototype of this motif in emblematics is an icon by Alciatus (Emblematum libellus)[11]; such an emblem can also be found in Saavedra’s collection[12]. In this case, the engraver had more room for shaping a new emblem by using symbols present in the Mazepa coat of arms. Jaworski formulated an inscription (lemmata) and a subscription, spanning 126 verses. The main stylistic means used are anaphoras and syntactic parallelisms, used for the amplification of the theme of the “victorious journey” of Ivan Mazepa. The other emblems in the work are constructed the same way. The technique of projection[13] (that is, inclusion) of iconographic signs from the Mazepa coat of arms onto picturae from West European books of emblems, as a result of which new (three-part) emblems are created, follows the scheme below (excluding the text of the subscription). The collection of images reveal the reserve of iconographic patters from which Jaworski could have drawn. The technique of transforming iconographic signs of the coat of arms through projection is used by Jaworski and his engraver in the (chronologically) following panegyric work, devoted to Barlaam Jasinski on the occasion of his appointment as metropolitan in the year 1690.

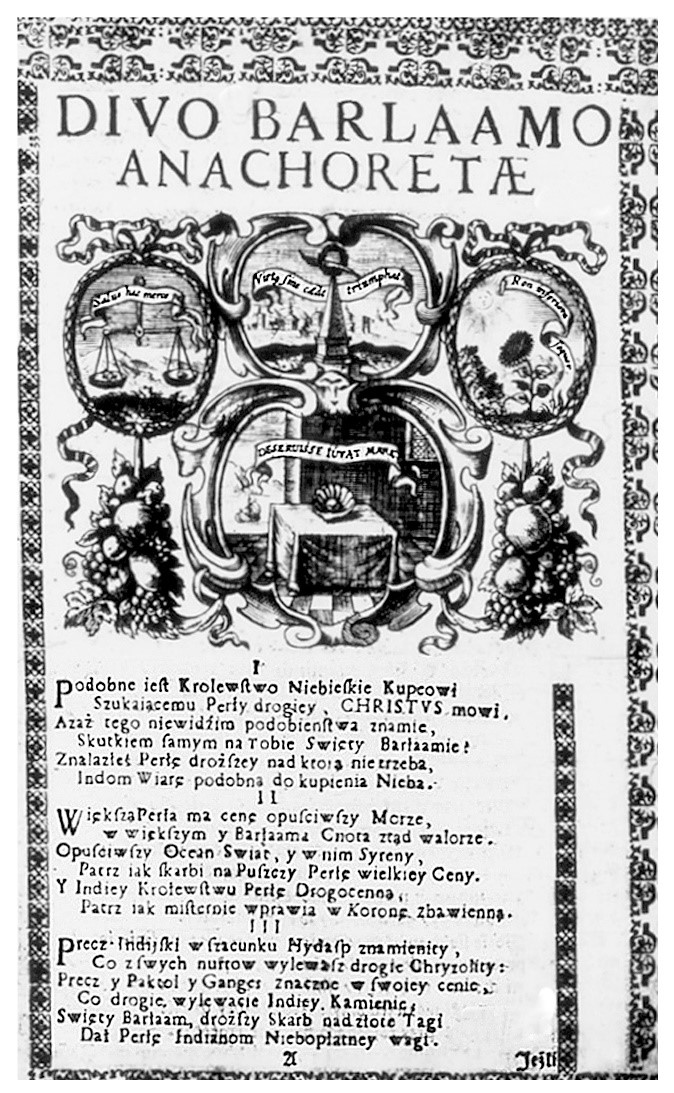

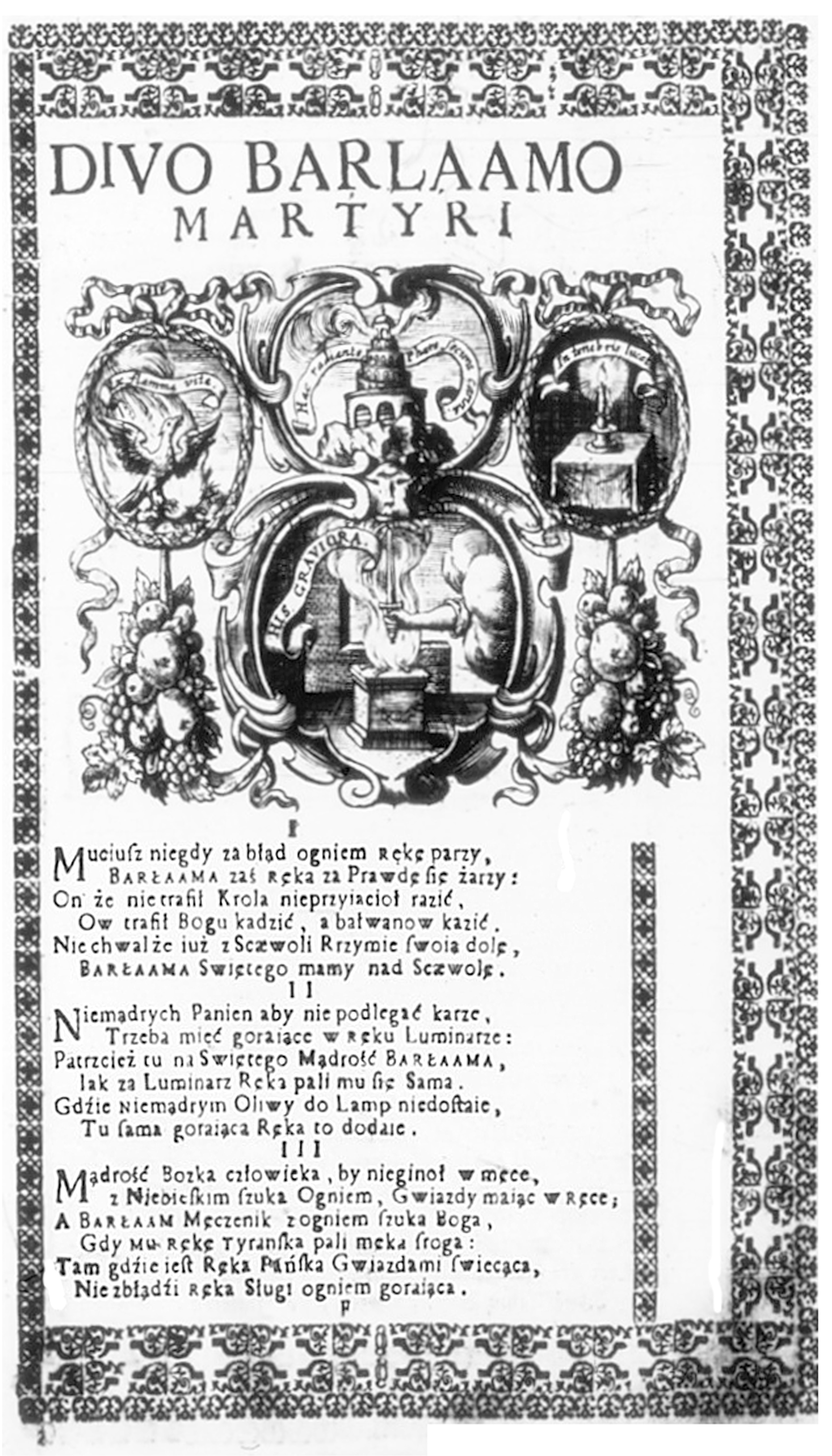

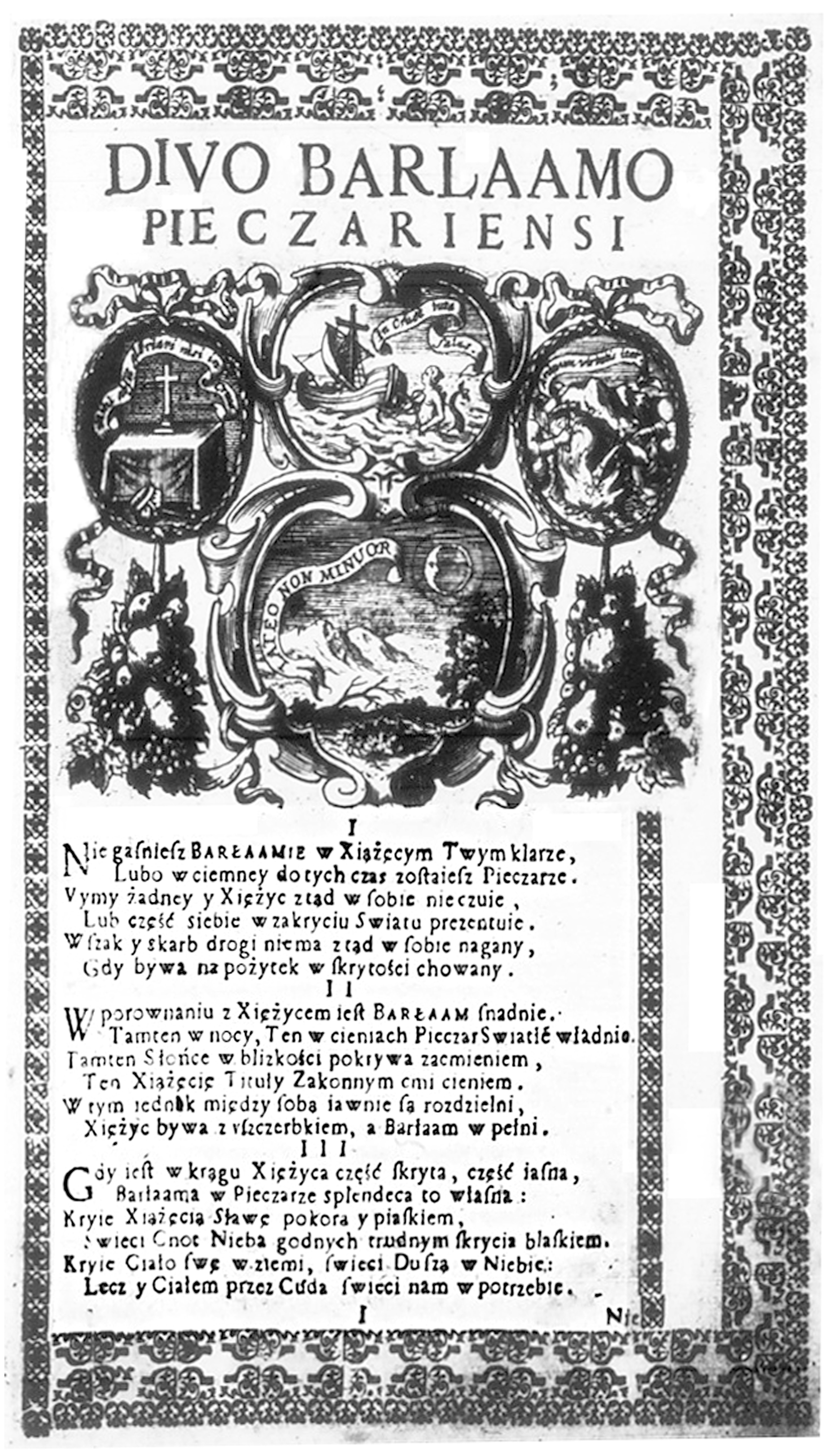

The Plenitude of Inexhaustible Glory (1691) Another example of Jaworski’s Polish-language emblematic practice is a 1691 panegyric, published in Kyiv (at the printing house of Pechersk Lavra), entitled The Plenitude of Inexhaustible Glory in the Heraldic Moon From Three Luminaries Primae Magnitudinis, Barlaam the Saint Hermit, Barlaam the Saint Martyr, Barlaam the Saint of Pechersk. The engraver hired to work on the collection was Leonidas Tarasiewicz, educated in Augsburg (ill. 8). This seventy-two-page piece consists in 1062 Polish verses (as well as Latin elogies). It is an attempt at a biographical synthesis, intended to present particular stages of the life and work of Barlaam Jasinski in pictorial-verbal combinations. The exordium alludes to the title page engraving, which is simultaneously a pictura of a newly-created emblem with inscriptions placed on ribbons. Jasinski’s coat of arms is shown twice: at the bottom in its authentic shape, while at the top – as a result of a transfiguration of the iconographic signs of the coat of arms. The face of the Mother of God is depicted on the moon, as explained by the subscription. Luna sub Pedibus Eius (Apocalypsa 12) Przeczystej Matki Bożej Miesiąc jest podnóże, (The Moon is the foothold of the Mother of God, / Next to it: two Stars and an Arrow. What is their significance? / The Star shines at night, as Faith and Hope / Only give help in the mortal life: / Faith is rightly bespoken by the First Morning Star, / As it starts the day with Faith since the rise of sin, / The Second Evening Star bespeaks Hope, / As it shines with trust at the sundown of life. / The arrow flying high is the Love for God / With it, the Moon of Humility at Mary’s feet.) The inscriptions in the emblem, through their intertextual references, signify the cosmic-biblical sphere. The words “Luna stetit in ordine suo”, printed inside the crescent moon, are a reference to the words of prophet Habakkuk: “The sun and moon stood still in their habitation: at the light of thine arrows they went, and at the shining of thy glittering spear” (Habakkuk 3:11)[14]. Three historical figures are standing on the moon: left, Saint Barlaam, holding the star from Jasinski’s coat of arms, with the inscription Pretium aeternitate (“The price of eternity”); center, Gaius Mucius Scaevola with the heraldic arrow protruding from his heart, with the inscription Amor addit alas (“Love gives wings”)[15]; right, Varlaam Pechersky (Варлаам Печерский) with the heraldic star and the inscription Clarius ut luceat (“How brightly he shines”). The narratio of the piece is also composed of three parts, recounting the lives and virtues of the three Saint Barlaams (the hermit, the martyr and the Pechersk monk), in order to commemorate and celebrate the author’s teacher and mentor once again:

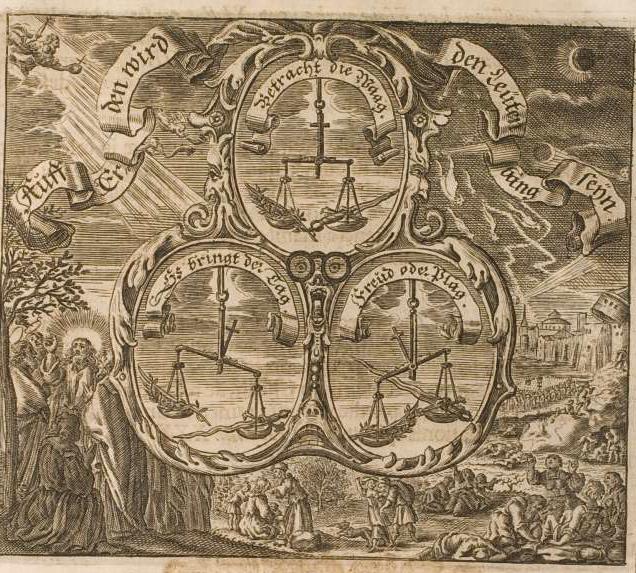

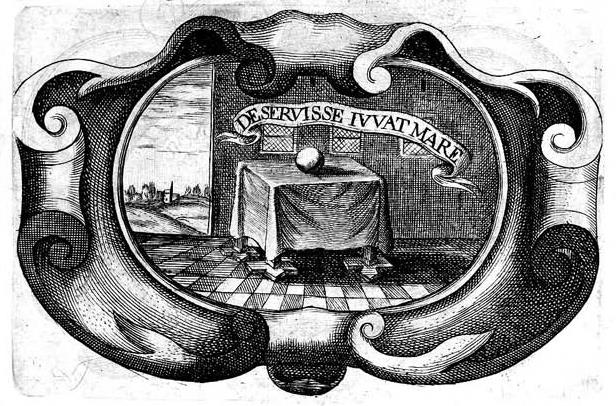

Each part is a pictorial-verbal combination, constructed on the basis of graphic patterns present in West European emblem books. In this piece, references to the German emblematic tradition can be seen specifically[16]. The technique of creating pictorial-verbal complexes was based on the authors’ and engravers’ conjunction of emblems with the same motifs or pictorial themes into one complex and adding the text of subscription. Representatives of such a technique included Franz Juliusz von dem Knesebeck, Johann Michael Dilherr and Georg Philipp Harsdörffer[17]. It differs from the most common emblematic technique of composing emblem books’ title pages by including several emblems. The technique of creating pictorial-verbal complexes was based on the authors’ and engravers’ conjunction of emblems with the same motifs or pictorial themes into one complex and adding the text of subscription [18]. Illustration 9 shows an example of such an emblematic complex from a collection by Dilherr, who collaborated with Harsdörffer (with the subscription omitted). In parts 1-3 of the narratio, Jaworski and his engraver Tarasiewicz have created complexes out of four distinct emblems. For example, into the center of the complex Divo Barlaamo Anachoretae (ill. 10) an emblem of a pearl is installed, with an inscription Deseruisse iuvat mare (“Fortunately she escaped the sea”), selected from a collection by Silvester Pietrasancta (ill. 11). Through the conjuction of the three emblem complexes (Divo Varlaamo Anachoretae – Divo Varlaamo Martyri [ill. 12] – Divo Varlaamo Pieczariensi [ill. 13]) and the intertextual references to stories and legends about the three saints in the subscriptions, an emblematic biography of Barlaam Jasinski emerges for the reader in the reading process. The conclusio of the piece contains a prose text. The author repeats and emphasizes the attributes of Jasinski’s virtues (gratitude, humility and charity) and elaborates on that theme in the final part, Mnemosyne sine recordatio patrocinii Stephanica.

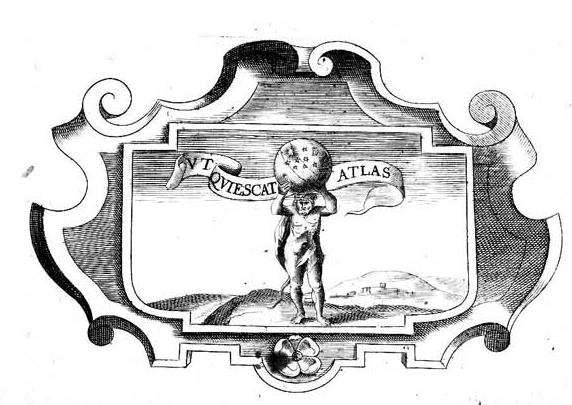

Conclusion In Polish-language panegyrics by Stefan Jaworski, two models of emblematic practice can be distinguished, having arisen in collaboration with Ukrainian engravers[19]: (1) creating new emblems through the inclusion (projection) of iconographic signs of the Mazepa coat of arms in The Echo of a Voice… into emblems from Saavedra’s collection and in Arctos et antarctos… through the transformation (transfiguration) of Jasinski’s coat of arms on the title page; (2) constructing emblematic complexes in the panegyric The Plenitude of Inexhaustible Glory… out of West European emblem books (Pietrosancta, Saavedra). In his construction of pictorial-verbal combinations, Jaworski prefers a three-part structure of the emblem (inscriptio – pictura – subscriptio), However, he introduces not one, but several inscriptions to his emblems (see The Echo of a Voice…), and the poems in the subscription always span several pages (without prose commentaries). His idea of an emblem approaches Masenius’ concept of pictorial-verbal combinations, which the latter presented in his late Baroque work Speculum Imaginum Veritatis occultae. Masenius describes emblema, symbolum, hieroglyphicum et aenigmatum with an superordinate term of imagines figuratae. There, the definition of the emblem can be found: Emblema est imago figurata, ab intelligentium rerum natura ad mores vitamque rei intelligentibus uno conceptu exponendum translata[20]. What follows from this definition is that the function of the emblem is oriented towards the interpretation of the moral sense (sensus moralis), which can be extended to the interpretational level of the anagogical sense (sensus angagogicus). Such a hermeneutic understanding of the emblem was very widespread in the writers’ milieu of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, so much so that it was the subject of courses in rhetoric and poetics (emblematicae declamationes). This is confirmed not only by definitions of the emblem in Kyivan handbooks of rhetoric, but above all by the Polish-language panegyrics by Stefan Jaworski, a professor of rhetoric and poetics, as well as the emblematic works of other “unknown” Kyivan poets, such as Filip Orlyk, who was Jaworski’s student in Kyiv, Jan Ornowski and Laurentius Krszczonowicz

Translated by: Aleksandra Paszkowska

[1] The precursor of (modern) research on the Polish-language works of ekstern Slavic poets on the former territory of the Polish republic in the seventeenth century, especially writers of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy circles, was Ryszard Łużny (1927–1998). See R. Łużny, Pisarze kręgu Akademii Kijowsko-Mohylańskiej a literatura polska. Z dziejów związków kulturalnych polsko-wschodniosłowiańskich w XVII–XVIII wieku, Kraków 1966; R. Łużny, Stefan Jaworski – poeta nieznany, in: „Slavia Orientalis” (1967), no. 16, pp. 363–376; R. Łużny, Twórczość Stefana Jaworskiego – poety ukraińsko-rosyjsko-polskiego czyli raz jeszcze o baroku wschodniosłowiańskim, w: Języki wschodniosłowiańskie. Materiały Ogólnopolskiej Konferencji Naukowej, Łódź 1979, pp. 103–114; W. Kroll, Heraldische Dichtung bei den Slaven. Mit einer Bibliographie zur Rezeption der Heraldik und Emblematik bei den Slaven (16.–18. Jahrhundert), Wiesbaden 1986. Łużny’s stipulations guided the works of his student Rostysław Radyszews’ki: R. Radyszews’kyj, Polskojęzyczna poezja ukraińska od końca XVI do początku XVIII wieku. Część I: Monografia. Kraków 1996; and an anthology – Roksolański parnas. Polskojęzyczna poezja ukraińska od końca XVI do początku XVIII wieku. Część II, ed. R. Radyszews’kyj, Kraków 1998. See also Giovanna Brogi Bercoff, Stefana Jaworskiego poezja polskojęzyczna, in: Contributi italiani al XII Congresso Internazionale degli Slavisti (Cracovia 26 Agosto – 3 Settembre 1998), Hg. F. Esvan, Napoli 1998, pp. 349–353. [2] Ф. А. Терновский, Митрополит Стефан Яворский. Биографический очерк, w: Труды Киевской духовной академии, Киев 1864, t. 1, p. 57. [3] See Catalogus librorum Stephani Jaworski, metropolitae Riazanensis et Muromensis, conscriptorum anno Domini 1721 mense Augusto, cum ex Divina gratia morbo pulsante sentiret se morti vicinum, in: С.И. Маслов: Библиотека Стефана Яворского. Киев 1914, pp. V–LV (Приложения). [4] See Д. Чижевський, Фільософія Г. С. Сковороди, Warszawa 1934; Д. Чижевський, Український літературний барок. Нариси. Частина третя, Прага 1944. See W. Kroll, Dmitrij Tschižewskij und die Emblematik. Versuch einer Rekonstruktion, w: D.I. Tschižewskij, Impulse eines Philologen und Philosophen für eine komparative Geistesgeschicht, Hg. A. Richter, B. Klosterberg. Berlin 2009, pp. 61–84; ibid. the bibliographic of his works on emblematics. New editions of the aforementioned works by D. Czyżewski, edited by Leonid Uszkałow, are also available on the Internet:: http://litopys.org.ua/chysk/chysk.htm. [5] For the bibliographic description see P. Buchwald Pelcowa, Emblematy w drukach polskich i Polski dotyczących XVI–XVIII wieku. Bibliografia, Wrocław–Warszawa–Kraków–Gdańsk–Łódź 1981, pp. 101–102; Я. Запаско, Я. Исаевич, Памятники книжного мистецтва. Каталог стародруків, виданих на Україні. Книга перша (1574–1700), Львів 1981. [6] See Д. В. Степовик, Леонтій Тарасевич і українське мистецтво барокко, Київ 1986. [7] This was noticed by Ryszard Łużny, Stefan Jaworski – poeta nieznany, op. cit.., p. 372. See M.C. Sarbievii, Lyricorum libri IV, Antverpiae 1634, pp. 116–117 (http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de); this exact edition was found in Jaworski’s library (see Маслов, op. cit., no. 587). [8] R. Radyszews’kyj, op. cit.., p. 227; B. Bergcoff, op. cit., pp. 353–354. [9] D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Idea de un príncipe político cristiano, Amstelodami 1659, no. 22. See Emblemata. Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVIII. Jahrhunderts, hrsg. von A. Henkel, A. Schöne, Stuttgart 1976, p. 762. [10] Jaworski’s collaboration with engravers is described by Smytro Stepovyk (see footnote 7 and 21). [11] Zob. Emblemata. Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst, dz. cyt., s. 385–386; wszystkie wersje z książek Alcatiusa można porównać w Internecie: http://emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/alciato/emblem.php?id=A56a004. [12] D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Idea principis christiano-politici [...], Bruxellae 1649, nr. 64. [13] See A. Hansen-Löve, Intermedialität und Intertextualität. Probleme der Korrelation von Wort- und Bildkunst. Am Beispiel der russischen Moderne, w: Dialog der Texte. Hamburger Kolloquium zur Intertextualität, Hg. W. Schmid und W.D. Stempel, Wien 1983, p. 304; A. Hansen-Löve distinguishes three differend methods of transforming verbal signs (Wort-Zeichen) and pictorial signs (Bild-Zeichen): 1. Transposition, 2. Transfiguration, 3. Projection. [14] Translator’s note: biblical quotes after King James Bible. [15] The inscription is a paraphrase of Psalms 55:6 „et dixi quis dabit mihi pinnas sicut columbae et volabo et requiescam (“And I said, Oh that I had wings like a dove! for then would I fly away, and be at rest”); it also appears in emblem books owned by Jaworski: Vaenius, Amorum emblemata, Antverpiae 1612, pp. 114–115 (Amor addit inertibus alas) and H. Hugo, Pia desideria, Antwerpen 1624, emblem 43 (http://emblems.let.uu.nl). [16] See I. Höpel, Das mehrständige Emblem: zu Geschichte und Erscheinungsform eines seltenen Emblemtyps, in: The Emblem in Renaissance and Baroque Europe. Tradition and Variety. Selected papers of the Glasgow International Emblem Conference, 13–17 August 1990, ed. by A. Adams, Leiden–New York–Köln 1992, pp. 104–117. [17] For the context of that technique, see I. Höpel, op. cit.; I. Höpel, Harsdörffers Theorie und Praxis des dreiständigen Emblems, in: G.P. Harsdörffer, Ein deutscher Dichter und europäischer Gelehrter, hrsg. J.M. Battaforano, Berlin 1991, pp. 195–234; D. Peil, Nachwort, in: J.M. Dillherr, G.P. Harsdörffer, Dreiständige Sonn und Festtag Emblemata oder Sinn Bilder, hrsg. D. Peil. Hildesheim–Zürich–New York, pp. 1–28. [18] G.Ph. Harsdörffer allows the composition of two to six emblems. See G.P. Harsdörffer, Frauenzimmer Gesprechspiele. Sechter Theil [...], Nürnberg 1646, p. 293 (http://diglib.hab.de/show_image.php?dir=drucke/lo-2622-6&pointer 483). [19] See Д. Степовик, Українська гравюра бароко: Майстер Ілля, Олександр Тарасевич, Леонтій Тарасевич, Іван Щирський, Київ 2012. I. Szczyrski, L. Tarasiewicz and O. Tarasiewicz were educated in the art of engraving in the Kilian family printing house in Augsburg among others. [20] J. Masen, Speculum Imaginum Veritatis occultae, Coloniae 1681, p. 656 (first ed. 1651). The definition of the emblem is repeated in the rhetorics of the Kiev-Mohyla Academy. In his overview of these handwritten and printed sources, V.P. Masljuk cites that definition (without an author noted in the manuscript). See В. П. Маслюк, Латиномовні поетики і риторики XVII–першої половини XVIII ст. Та їх роль у розвитку теорії літератури на Україні, Київ 1983, p. 177; see also T. Michałowska, Staropolska teoria genologiczna, Wrocław–Warszawa–Kraków–Gdańsk 1974, p. 139, pp. 168–169. On the lexical ambiguity of the term „emblem”, see also M. Górska, Ut pictura emblema? Teoria i praktyka, in: Ut pictura poesis / ut poesis pictura. O związkach literatury i sztuk wizualnych od XVI do XVIII wieku, ed. A. Bielak, Warszawa 2013, pp. 31–46. |

Ill. 1. Stefan Jaworoski, Arctos et antarctos caeli Rossiaci in gentilibus syderibus [...] Barlaami Jasinski Kijoviensis Haliciensis totigq. Rossiae orthodoxi archiepiscopi metropolitae (Ławra Pieczerska, Kijów 1690) Ill. 3. Stefan Jaworski, Echo głosu wołającego na puszczy od serdecznej refleksyj pochodzące [...], Kijów 1689.

Ill. 7. Diego de Saavedra Fajardo, Idea principis christiano-politici [...], Bruxellae 1649, nr 64.

Ill. 8. Stefan Jaworski, Pełnia nieubywiącej chwały [...], Kijów 1691 (frontyspis).

Ill. 9. M. Dilheer, Heilige Sonn – und Festtags-Arbeit/ Das ist: Deutliche Erklärung Der jährlichenSonn– und Festtäglichen Johann Evangelien [...], Nürnberg 1674, s. 16. (http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/c-321-2f-helmst/start.htm).

Ill. 12. Stefan Jaworski, Pełnia nieubywiącej chwały [...], Kijów 1692, Divo Barlaamo Martyrii.

|