MACIEJ WIECZOREK

TOMASZ TRETER IN VIEW OF THE ENGRAVING WORKS OF CORNELIS CORT

|

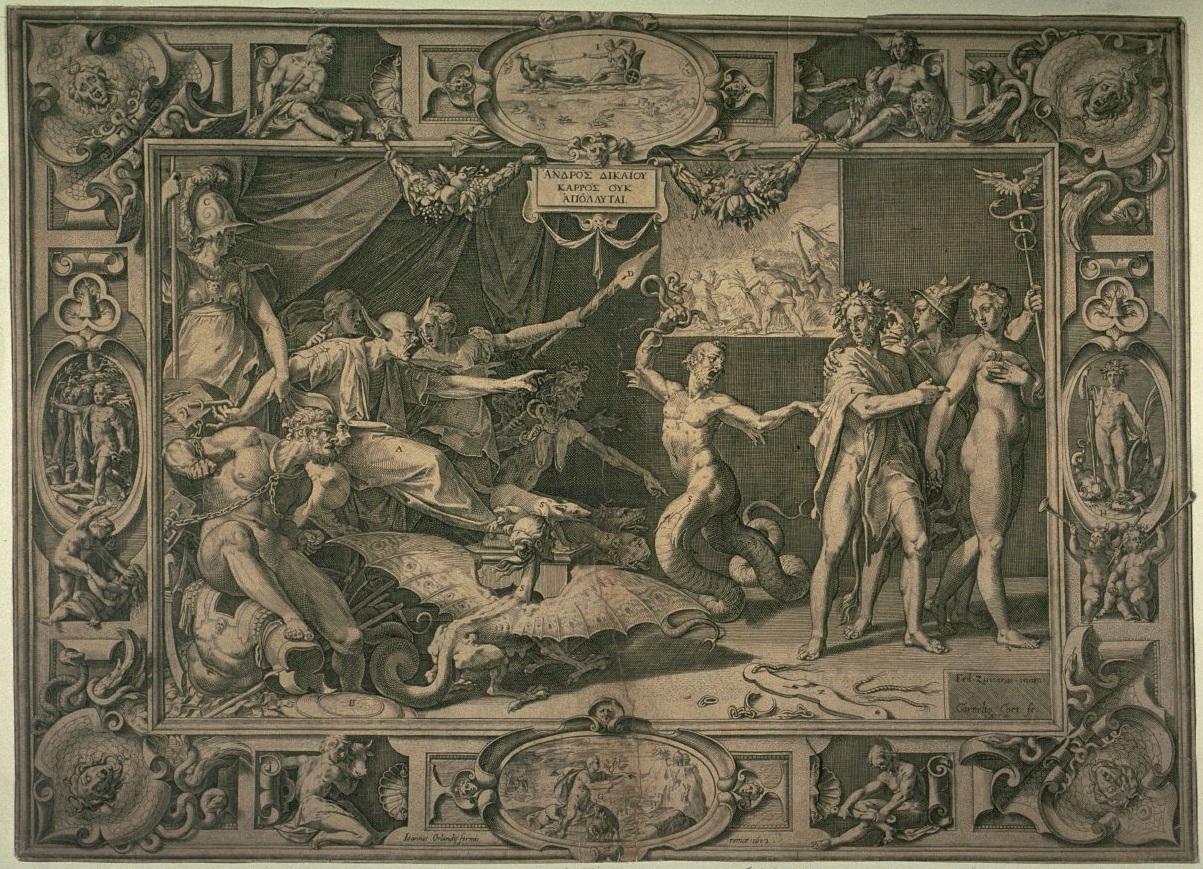

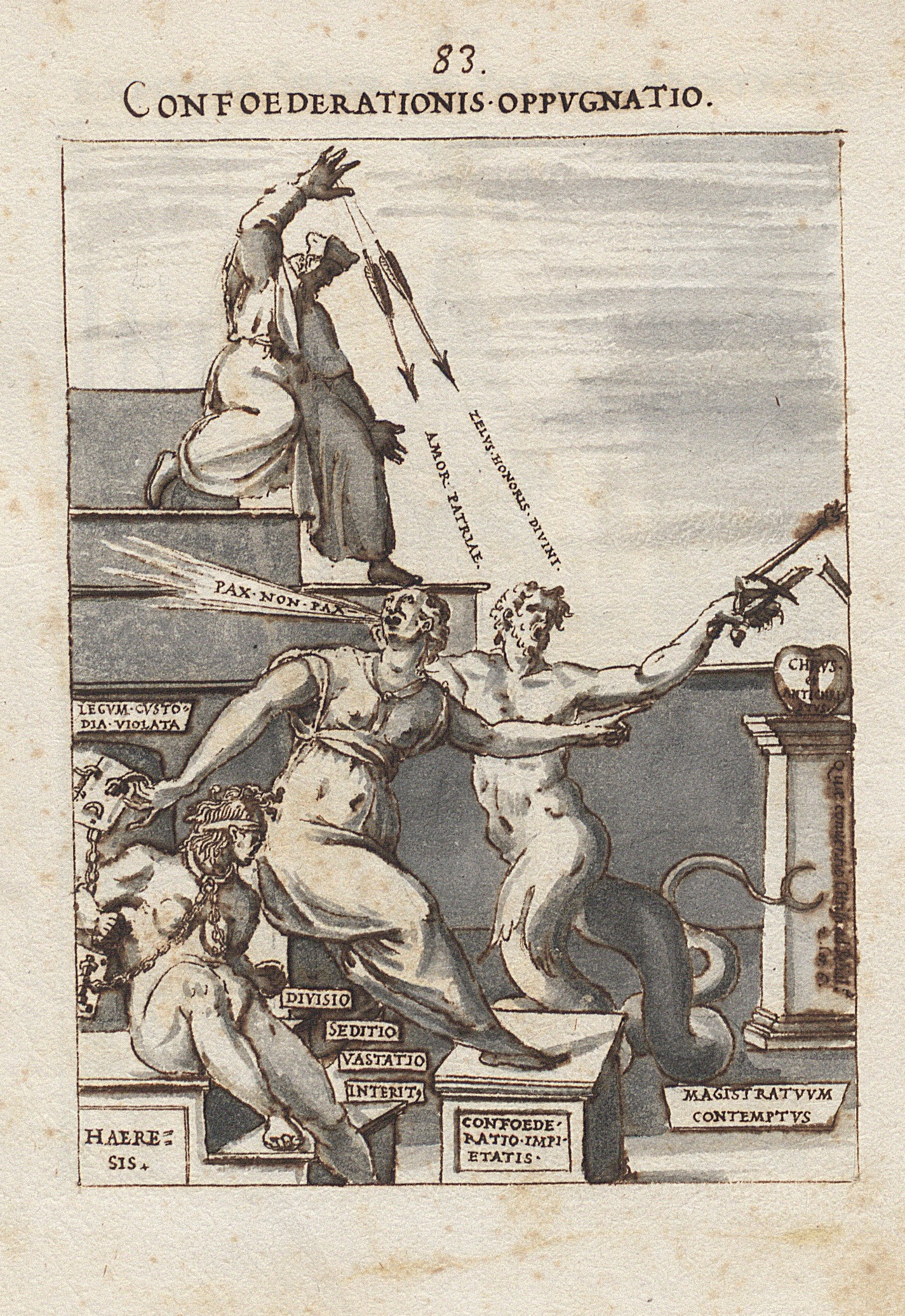

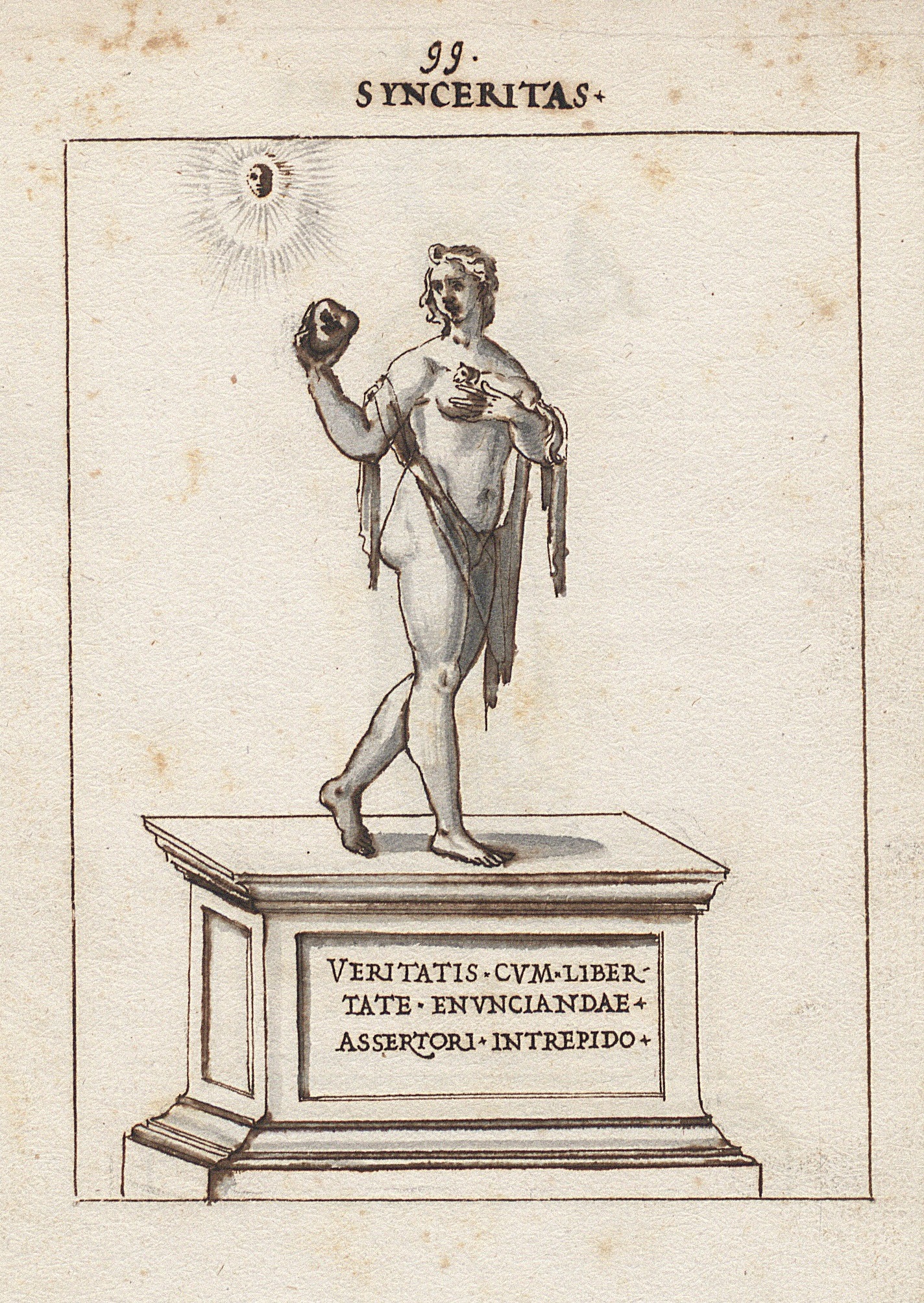

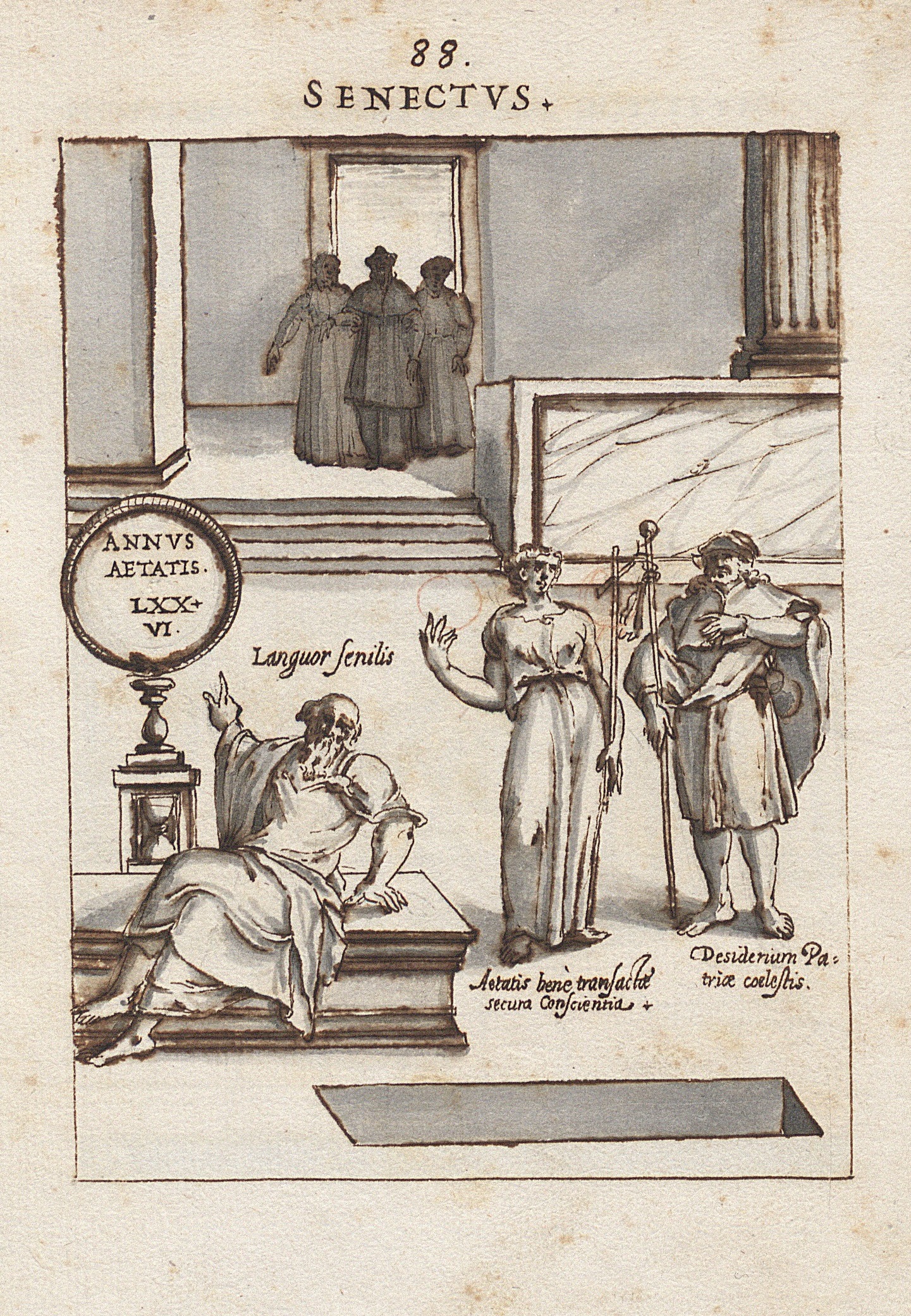

A collection of Tomasz Treter’s drawings[1], stored in the Department of Manuscripts of the National Library of Poland, is an item of unique value. It is a tentative sketchbook for the cycle of emblematic copperplates entitled Theatrum virtutum ac meritorum D. Stanislai Hosii…, devoted to cardinal Stanislau Hosius[2]. It is also a rare sixteenth-century case in Polish art history in which finished graphic artwork was preceded by a preparatory, drawn concept. The uniqueness of the collection is amplified by its unusual authorship. Born in an impoverished family of burghers from Chwaliszewo, a city then separate from Poznan, Tomasz Treter (1547–1610) was not a professional engraver[3]. Instead, this clergyman and Doctor of Law, alum of the Jesuit school in Braniewo, was a close associate of Stanislaus Hosius, Andrzej Batory and Anna Jagiellonka[4]. He resided in Rome in the years 1569–84 and 1586–93[5]. The drawings in question were created during his first sojourn in the Eternal City. Art historian Tadeusz Chrzanowski assumes that Treter began working on his drawings as early as 1579, immediately following Hosius’ death, and completed the cycle in 1580 or soon after[6]. On the other hand, Grażyna Jurkowlaniec has extended the timeframe of the manuscript’s creation, dating its execution between August 1579 and August 1582[7]. The subject of Theatrum virtutum… has already been discussed in a number of publications[8]. However, they lack an exhaustive analysis of the collection itself in the context of its artistic debt to works of renowned Roman artists of the last quarter of the sixteenth century[9]. It is beyond any doubt that Treter, as a non-professional artist, was simply forced to draw inspiration and compositional patterns from other creators, in this case engravers in specifically. The mere intention of publishing the drawings as copperplates must have determined the field of artistic influence to a certain degree. This paper could by no means accommodate a thorough examination of all Treter’s emblems in relation to his contemporary graphic production. Here, I would like to analyze Treter’s drawings with respect to their relationship to the works of one engraver: Cornelis Cort. Cort (1533–1578) was among the most valued sixteenth-century engravers[10]. Beginning in 1565, his activity is documented in Venice, and starting in 1567, he strived to publish his pieces in Rome[11]. No doubt remains, then, that during his stay in the Eternal City, Treter had contact with Cort’s engravings circulating there[12]. Indeed, one can find references to the compositions of Cornelis Cort’s five copperplates: The Adoration of the Holy Trinity, The Birth of Mary, Calumny of Apelles, The The Practitioners of the Visual Arts and Saint Roch in the sketchbook for Theatrum virtutum…. The Adoration of the Holy Trinity (ill. 1), based on a painting by Titian, is dated to the year 1566[13]. Cort’s composition depicts the Holy Trinity surrounded by angels in the heavens: the throning Jesus Christ, Father God, and a white dove above them. In the lower part of the composition, Old Testament prophets are placed alongside the Church’s saints, immersed in adoration. It is the pose of one of these figures that Treter used in his drawing for his emblem number 44[14], entitled Confutatio Prolegomenon Brentii (ill. 2). The heretic Johann Brenz, portrayed in that illustration, was given the pose of the reclining Moses from Cort’s engraving. Only the folds of Moses’ robes and his attributes were slightly modified: two books took the place of the Tables of the Law. Otherwise, the figure of the prophet was copied by Treter fairly faithfully. Cort engraved The Birth of Mary (ill. 3), dated to 1568[15], after a drawing by Federico Zuccaro, which was likely based on a lost composition by Taddeo Zuccaro[16]. In the foreground of the composition, the new-born Mary is depicted, tended to by nurses and angels. In the background, a bed with a resting Saint Anne adds a horizontal counterpoint to the composition. Treter employed some components of the foreground of The Birth of Mary in drawing 14 of his cycle, entitled Doctoratus[17] (ill. 4). Two allegorical figures, representing jurisprudence and sitting on both sides of cardinal Hosius, have been modeled on Mary’s nurses as drawn by Cort. In addition, Treter based his design for emblem 28, entitled Sigismundi. I. Regis. Testamentum[18] (ill. 5), on the composition of the background in Cort’s drawing. The bed along with the figure of Saint Anne was entirely copied by Treter. All components have been replicated in minute detail. Even the draping of curtains was faithfully drawn according to the original. Only the face of the female saint has been changed into the physiognomy of Sigismund I the Old, and the figure of his son, Sigismund II Augustus, was added to the right. Cort’s Calumny of Apelles, dated to 1572[19], was also engraved after a composition by Federico Zuccaro. In his work, the younger Zuccaro brother adopted a common Renaissance theme of the lost painting by Apelles. On the right-hand side of the composition, the Hero can be seen, holding Innocence by the hand. Innocence is depicted as a nude woman carrying an ermine. The two figures are being protected from calumny by Mercury. To the left-hand side, a group of “villains” is shown. King Midas with donkey years listens to the whispers of Suspicion and Calumny. He points at the Hero with his left hand, while trying to release Rage from its shackles with his right, from which the goddess Athena is stopping him. Around the figures, the artist has placed a number of grotesque creatures, human-animal hybrids. Treter used components of this complex piece in two of his emblems. Emblem 83 entitled Confederationis opugnato[20] (ill. 7) is based on the group of “villains” as drawn by Cort. The sitting silhouette of Midas was replaced with a female personification of the Warsaw Confederation. Rage, shackled to a rock, was drawn as a Gorgon and personifies Heresy, whereas the merman-like snake-legged monster represents the Devil. The monstrous figure was fairly accurately copied by Treter, who changed the positioning of its arms and added two attributes: a broken sword and a scepter. The female figure of Innocence, leading the Hero by the hand on the right-hand side of Cort’s Calumny of Apelles, found its way to Treter’s drawing 99, entitled Synceritas[21] (ill. 8). Innocence, adapted as Sincerity, has retained its original attribute – the ermine, held in the left hand. However, the figure’s right hand is raised to the face and holding a heart. In addition, a gauzy veil has been draped over the naked body. The next engraving in chronological order is The Practitioners of the Visual Arts (ill. 9), created in 1578 based on a drawing by Jan van der Straet[22]. Through its depiction of artists in a workshop, the scene presents a range of fine arts, including printmaking, anatomy, wall painting, monumental sculpture and others. It is the latter representation, called “Statuatoria”, which became a model for Treter’s first, opening emblem – Patria et Natalis dies[23] (ill. 10). In Cort’s engraving, a sculptor can be seen, chiseling a statue of Rome in marble. The goddess is holding a small figurine of Victory in her right hand, raised to eye level, and a scepter in her left hand, resting on her knee. At her feet, a bearded man reposes, personifying the river Tiber, along with a she-wolf nursing Romulus and Remus. In his own design, Treter transformed Rome into Cracovia and Tiber into Vistula. The composition was replicated to be almost identical. Only some attributes have been added: a model of the city in the goddess’ right hand, a crown on her helmet and the coat-of-arms of the city of Krakow in place of the she-wolf. Treter referred to Cort’s Practitioners… in one more of his drawings. Far from being a reference strictly speaking, a fragment of the more advanced artist’s composition was used as a drawing prop. In emblem 15 Benedictio paterna[24] (ill.11), Treter copied the positioning of the sitting engraver’s legs from the lower left-hand corner of Cort’s piece. The Polish artist duplicated the contour of the table, the legs, robes and the stool on which Cort’s engraver is sitting. The last engraving of Cornelius Cort emulated by Tomasz Treter is the depiction of Saint Roch. Cort’s engraving, based on a composition by Hans Speckaert, was first printed in 1577[25]. The standing silhouette of the saint in pilgrim’s robes was copied in emblem 88 of Treter’s cycle, entitled Senectus[26] (ill. 13). Saint Roch became a model for a figure personifying the longing for a home in heaven. One can easily note that Treter referred directly to a copy of Cort’s engraving, made in 1580 by Agostino Carracci (ill. 12), as the altered composition would suggest[27]. It is clear that Tomasz Treter knew Cornelis Cort’s engraving work very well. In his drawings, the Polish canon referred to engravings published over the course of 25 years. This means that Treter followed Cort’s artistic development and even must have owned the Dutchman’s graphic works. What other conclusions can one draw from the observations above? First, that the dating of Treter’s drawings needs revisiting. As mentioned above, Tadeusz Chrzanowski in his monograph on Treter dateed the creation of the sketches to directly after Hosius’ death, that is, as soon as 1579[28]. However, the most recent engraving on which Treter based his drawings was not published until 1580[29]. On that basis, the lower limit of dating Treter’s cycle should not exceed the year 1580. What is more, new light is shed on Treter’s artistic taste. So far, the artist has been described as a collector of emblems, sententiae and polonica in the form of images of Polish saints and rulers[30]. Yet, as proven in this paper, Treter also displayed a penchant for works of very high artistic value. As argued above, the engravings which are the subject of this article must have been in possession of the clergyman, and thus can give the researcher a clearer vision of the scope of Treter’s collection. In addition, it becomes undeniable that through his collection, Treter knew the works of such artists as Titian, Jan van der Straet or the Zuccaro brothers. The creations of the brother, Federico, had a significant presence in the Roman milieu of the late 1500s[31]. One could therefore speculate about the orbit of artistic influence in which Treter found himself. Yet, besides the Pole’s relations with Giovanni Battista de’ Cavalieri[32] and his collaborators, or mentions of engravings by Giulio Bonasone[33] and Adamo Scultori[34], only Treter’s inspiration by Niccolo Carcignani’s[35] frescos has been discussed so far. On the basis of the juxtaposition of engravings and drawings presented in this paper, Tomasz Treter’s mode of working can also be defined to a certain degree. The several examples given demonstrate that he created his drawings based on other artists’ compositions. At times, he transposed entire arrangements of figures, at other times – only selected components[36]. However, in any case, Treter copied existing patterns in a literal manner, rather than being inspired by others’ works indirectly. The most obvious example of such a modus operandi is his duplication of the banal fragment of a table and the leg of the man sitting at it. In the light of these facts, Tomasz Treter cannot be considered as an independent artist[37]. Rather, he seems to be a dilettante who engages in artistic activities on the margin of his primary duties[38]. Therefore, it is worth to reconsider the attribution of some key art pieces to him, including the tomb of Stanislaus Hosius in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere[39], the design for the fresco of the Council of Trent in the Altemps Chapel at the same basilica[40], or the tomb of Bona Sforza in the Basilica of St. Nicholas in Bari[41]. Indeed, one can assume that Treter could have influenced the intellectual program of these realizations. However, in the light of the observations above, it seems doubtful that the Polish artist also authored their visual realization. Tomasz Treter, a dilettante, constructor of eclectic arrangements out of others’ components – this is the vision of the artist suggested by the diagnoses above. Still, his dilettantism is of extraordinary interest to the researcher. Apart from the fact that Treter is likely the first known example of a Polish amateur artist, the erudite character of his art opens up a new scope of research. From this viewpoint, the sketchbook for Theatrum virtutum… reveals itself to be a collection of fragments drawn from other artists’ compositions with which the Polish canon came in contact. Identifying these motifs would provide information on artworks to which Tomasz Treter referred directly. On such basis, an attempt at a reconstruction of the Treterian library could be made, and the notion of the artistic taste of the Polish humanists could be revised. Unfortunately, written sources give a very modest image of this, both in the case of Tomasz Treter[42] and his fellow countrymen[43]. Undertaking extensive research on the designs for Theatrum virtutum… stored at the National Library of Poland could surely shed more light on the question of art reception in the age of the Polish Renaissance.

Translated by: Aleksandra Paszkowska

[1] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130. [2] T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna Tomasza Tretera, Warszawa 1984, pp. 91–92. [3] Bibliografia Literatury Polskiej – Nowy Korbut, t. 3 Piśmiennictwo Staropolskiej, ed. R. Pollak, Warszawa 1965, pp. 345–347. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. [6] Moreover, relying on Reszko’s letter to Kromer dated August 11th, 1582, Chrzanowski indicates that the drawings must have been ready then. T. Chrzanowski, op. cit., p. 97. [7] G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość Rycin. Rzymska twórczość Tomasza Tretera i jej europejskie oddziaływanie, Warszawa 2017, p. 248. [8] K. Beyer, Rysunki oryginalne Tomasza Tretera kanonika warmińskiego z drugiej połowy XVI w., offprint, Warszawa 1868; J. Umiński, Zapominany rysownik i rytownik polski XVI w., ks. Tomasz Treter i jego „Theatrum virtutum D. Stanislai Hostii”, „Collectanea Theologica” 1932, pp. 13–59, here pp. 44–58; T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna…, pp. 91–108. M. Górska, Polonia – Respublica – Patria. Personifikacja Polski w sztuce XVI–XVIII wieku, Wrocław 2005, pp. 178–180; J. Talbierska, Grafika XVII wieku w Polsce. Funkcje, ośrodki, artyści, dzieła, Warszawa 2011, pp. 107–108; G.Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin..., pp. 242–254. [9] So far, only several of Treter’s drawings have been analyzed with regard to their dependence on other works of art: Chrzanowski has analyzed compositions 50, 62 and 82 – T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna..., pp. 72–74, 130–133; Górska has defined the entire collection as inspired by the engravings of Giulio Bonasone, which illustrate Achille Bocchi’s Symbolicarum questionum, de Universo genere, quas serio ludebat, libri quinque, published in Bologna in 1555 and in 1574 – M. Górska, Polonia – Respublica – Patria…, p. 179, footnote 14; Jurkowlaniec has analyzed the Frontispiece, the portrait of Hosius and compositions 1, 50, 62, 69 and 82; she revised the conclusions drawn by Chrzanowski, maintained the opinion of Górska (referring to the portrait of Hosius), indicated the influence of engravings by A. Scultori after Buonarotti (frontispiece, composition 69), of C. Cort’s engraving created after the drawing of Jan van der Straet (composition 1) as well as of the graphic cycle Seculum Romanae magnificentiae – G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość Rycin…, pp. 248–253. [10] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 1, Rotterdam 2000, p. XIII. [11] Ibid., p. XV–XVI. [12] Jurkowlaniec has indicated the dependence of the drawn composition Patria et Natalis dies (ill. 10) on the engraving by Cort The Practitioners of the Visual Arts (ill. 9); G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, s. 252. [13] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 40. [14] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 52 verso. [15] Ibid. [16] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, s. 80. [17] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 22 verso. [18] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 36 verso. [19] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 3, Rotterdam 2000, p. 126. [20] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 91 verso. [21] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 107 verso. [22] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 3, Rotterdam 2000, p. 119. [23] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 5 verso. [24] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 23 verso; see: footnote 12. [25] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 205 [26] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 96 verso. [27] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 205 [28] T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna…, pp. 91–92. [29] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 205 [30] T. Chrzanowski, Uwagi o intelektualiście-kolekcjonerze w Polsce na przełomie renesansu i baroku, in: Mecenas, kolekcjoner, odbiorca. Materiały Sesji Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki, Katowice, November 1981, Warszawa 1984, pp. 121–145, here p. 144. [31] A. Blunt, Artistic Theory in Italy 1450-1600, Oxford 1940, pp. 138–147. [32] J. Umiński, Zapominany rysownik…, p. 24–26; J. Hess, Note Manciniane, „Munchener Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst”, v. 19, 1969, p. 114; T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna…, pp. 68–74; J. Talbierska, Grafika XVII wieku…, pp. 104–106, 108, 218; G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, pp. 213–226. [33] See: footnote 9. [34] Ibid. [35] Hess also writes about evident inspirations by the works of Circignani in the case of two easel paintings by Treter – J. Hess, Note Manciniane…, p. 111; Chrzanowski assumes Hess’s conviction and in a way extends it to the entire works of Treter, making him an imitator of Circignani’s – T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna… pp. 71, 127–128, 152; Talbierska maintains Chrzanowski’s opinion – J. Talbierska, Grafika, XVII wieku…, p. 104; Jurkowlaniec stresses the inspiration by Circignani’s works in the case of the aforementioned easel paintings, but does not define him as an imitator – G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, pp. 290, 291. [36] This is further indicated by the observations of Jurkowlaniec, see: ibid., pp. 248–252. [37] Jurkowlaniec, discussing the drawing Censura de haereticorum censura as an example, concludes that despite Treter’s frequent use of finished compositions, the designer tried to creatively adapt popular motifs. To my mind, however, absolute certainty can only be attained through the examination of Censura… with respect to contemporary graphic patterns available to Treter. Moreover, it seems unlikely that the figures of prisoners of war in that composition were modeled on the ignudi from Adamo Scultori’s engravings; ibid., pp. 252–254. [38] See: T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna… p. 147, footnote 52. In one footnote Chrzanowski characterizes Treter as a dilettante who imitates and borrows in order to facilitate his work. Yet, this remark was not elaborated upon. Further, it was only made in reference to frescos supposedly designed by Tomasz Treter and painted by Pasquale Cati, see ibid. pp. 129–130. [39] T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna… pp. 87–91. [40] Both Chrzanowski and Jurkowlaniec claim that the model for the composition of Pasquale Cati’s fresco was engraving 58 from the cycle Theatrum virtutum… . The direction of inspiration is, to my mind, disputable and needs a more thorough examination; ibid., pp. 131–132; G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, pp. 297–300. [41] Z. Waźbiński, Mauzoleum Bony Sforzy w Barii, Przyczynek do dziejów polityki dynastycznej królowej Anny, ostatniej Jagiellonki, „Folia Historiae Artium”, 1979 s. 59–86; Jurkowlaniec finds Treter’s authorship to be a speculation not sufficiently founded in sources – G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, p. 278. [42] Thus the aformentioned conclusions by Chrzanowski that Treter would only have been interested in emblems, polonica and images of saints. T. Chrzanowski, Uwagi o intelektualiście-kolekcjonerze…, p. 144; See also: T. Tretero, Symbolica vitae Christi meditatio, typis Georg Schoenfels, Brunsbergae 1612, foreword by Schoenfels. [43] Tomkiewicz, analyzing sixteenth-century accounts of pilgrimages to Italy, notices that Polish travelers did not pay particular attention to the name of the artist, the composition nor the proportions in the work of art. They were most impressed by monumentalism, the materials used as well as the pricing of a work of art. Similar conclusions are drawn by Lepacka in her analysis of the diary of Stanislaw Reszka, who was closely connected to Treter and Hosius; W. Tomkiewicz, Pisarze polskiego odrodzenia o sztuce, Wrocław 1955, pp. 44, 55–56, 85 ; Anna Maria Lepacka, Michel de Montaigne i Stanisław Reszka: o wrażliwości estetycznej humanistów podróżujących po Italii w drugiej połowie XVI wieku, in: „Relacje kulturalne między Italią a Polską w epoce nowożytnej”, pp. 49–75, Warszawa 2016, pp. 66–69. |

|