News UK

WALTER KROLL

STEFAN JAWORSKI AND EMBLEMATICS

|

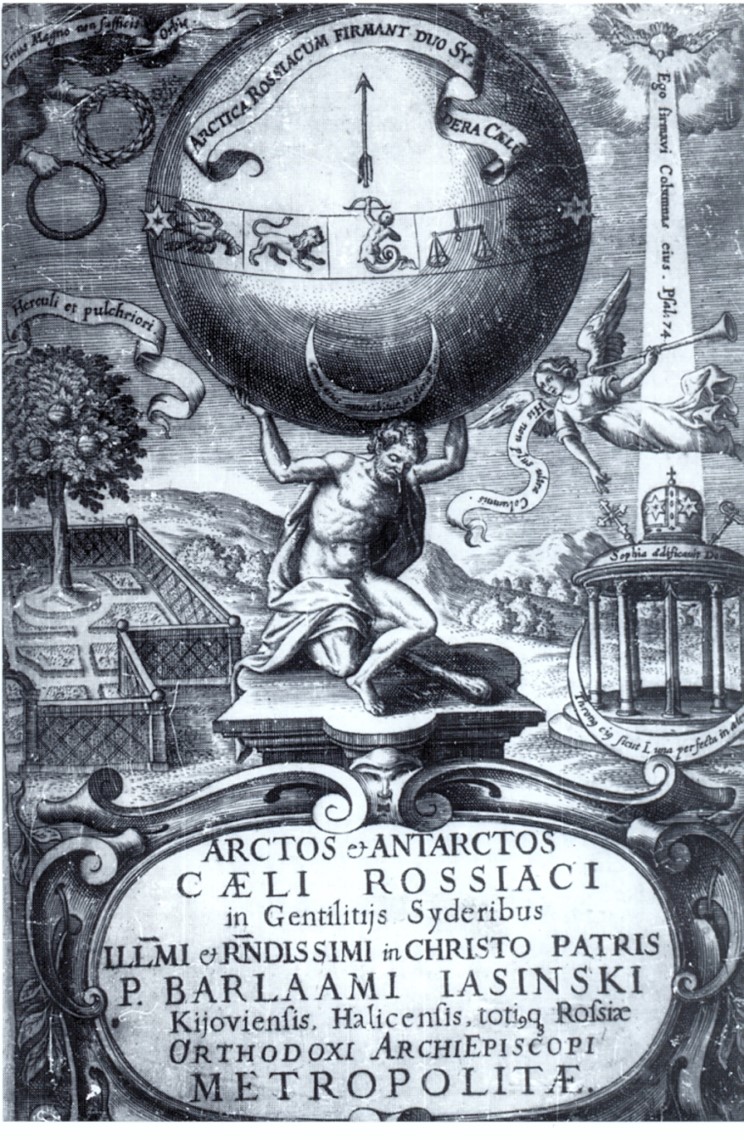

Stefan Jaworski (1658–1722) is one of the „unknown”[1] Polish-speaking poets of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy’s trilingual milieu in the era of Baroque. Russian, Ukrainian and German readers consider him primarily as a bishop – metropolitan of Ryazan, preacher and theologian. However, the context of Orthodox Christianity masks the Polish implications of his works, stemming from his education. Having graduated from the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in the year (circa) 1684, he attended Jesuit colleges in Lviv, Lublin, Poznan and the Academy of Vilnius. In these schools, Jaworski perfected his knowledge of Polish and Latin, also extending his competencies in rhetoric, poetics, philosophy, theology and homiletics. After his return to Kyiv, where was awarded the title of poet laureate (лавроносный пиит)[2], Jaworski gave rhetoric, and later philosophy and theology lectures at the College in the years 1690-1700. In 1700, Tsar Peter the Great appointed Stefan Jaworski metropolitan of the Ryazan-Murom eparchy. In his library (whose precise description he created shortly before his death in 1721[3]), Jaworski housed over 600 volumes from different fields of science and literature, including a number of emblem books: (1) Diego de Fajardo Saavedra, Idea de un principe politico christiana (Amstelodami 1659); (2) Hermann Hugo, Pia desideria (Antverpiae 1624); (3) Otto Vaenius, Amorum emblemata (Antverpiae 1612); (4) Jeremias Drexel, Zodiacus christianus (München 1618); (5) Maximilian Sandaeus, Maria Flos Mysticus (Moguntiae 1629); (6) Henricus Engelgrave, Lux Evangelica sub velum Sacrorum Emblematum Recondita (Antverpiae 1648); (7) Henricus Engelgrave, Caeleste pantheon, sive caelum novum, in festa et gesta sanctorum totius anni morali doctrina, ac profana historia varie illustratum (Coloniae Agrippinae 1671); (8) Sebastian a Matre Dei, Firmamentum Symbolicum (Lublini 1652); (9) Andrzej Młodzianowski, Icones symbolicae (Vilnae 1675); (10) Ioannes Michael von der Ketten, Appelles symbolicus (Amstelaedami et Gedani 1699); (11) Daniel de la Feuille, Devises et emblèmes (Amsterdam 1691); (12) Symbola et Emblemata selecta (Amsterdam 1705). Moreover, Jaworski and his engraver Szczyrski had at their disposal the collections of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy library and the libraries of Kyivan writers such as Połocki and Prokopowicz, containing the entire canon of West European emblem books and a number of Polish heraldic compendia (Szymon Okolski, Orbis Polonus, 1641; Bartosz Paprocki, Panosza, 1575; Herby rycerstwa polskiego, 1584; Wacław Potocki, Poczet herbów, 1696). This is confirmed by the research of Dmytr Czyżewski (1894–1977) on the reception of emblematics in Ukraine in the era of Baroque[4], which was pioneering, although long-ignored in the Soviet Union. Jaworski created his Polish-language works in the period of 1684–1691, that is, at the close of the era of Baroque, when the reception of emblematics in the Kyiv-Chernihiv-Lviv region was still extensive and prolific. At that time, Jaworski authored four panegyrics[5]. The first two were not accompanied by engravings and therefore are not pictorial-verbal combinations strictly speaking: Hercules post Atlantem infracto virtutum robore honorarium pondus sustinens (Chernihiv, in the Swieto-Trojecka Ilinska printing house, [ca. 1684]) as well as Arctos et antarctos caeli Rossiaci in gentilibus syderibus [...] Barlaami Jasinski Kijoviensis Haliciensis totigq. Rossiae orthodoxi archiepiscopi metropolitae (Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv 1690). Except for its title page and the stemmat of Jasinski’s coat of arms, Arctos… is devoid of any pictorial components. The artful engraving of the title page depicts Atlas holding up the firmament (coelum Rossiacum) on which the engraver (Leontij Tarasiewicz)[6] has placed the Zodiac, Jasinski’s coat of arms and some inscriptions on ribbons. The image of Atlas was likely modeled on an icon from an emblem book by Jesuit Silvester Pietrosancta. Here, Jaworski refers to the subject of mythology from his first piece (Herkules post Atlantem), treating it in cosmic dimensions: the arrow from the coat of arms points north, to the pole star (arctos – the Great Bear); in Greek, antarctos means “opposite the bear”, thus the name of Antarctica. The author uses his key word arctos in order to set in motion the symbolism of light and brightness (jasność), from which he etymologically derives the name Jasinski. Among the plethora of quotations from and allusions to the Bible and classical literature (such as Metamorphoses by Ovid) – proofs of the intertextual quality of the work – it is easy to miss a passage from a book of songs (Lyricorum libri IV, book IV, ode 13) by Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski, to whom Jaworski refers using the antonomasia “Horacjusz Sarmacki”[7]. These data show that Jaworski was familiar not only with Sarbiewski’s treatise on the point and the joke, but also his new Latin poetry.

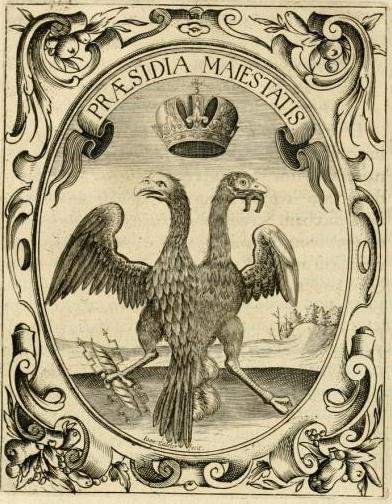

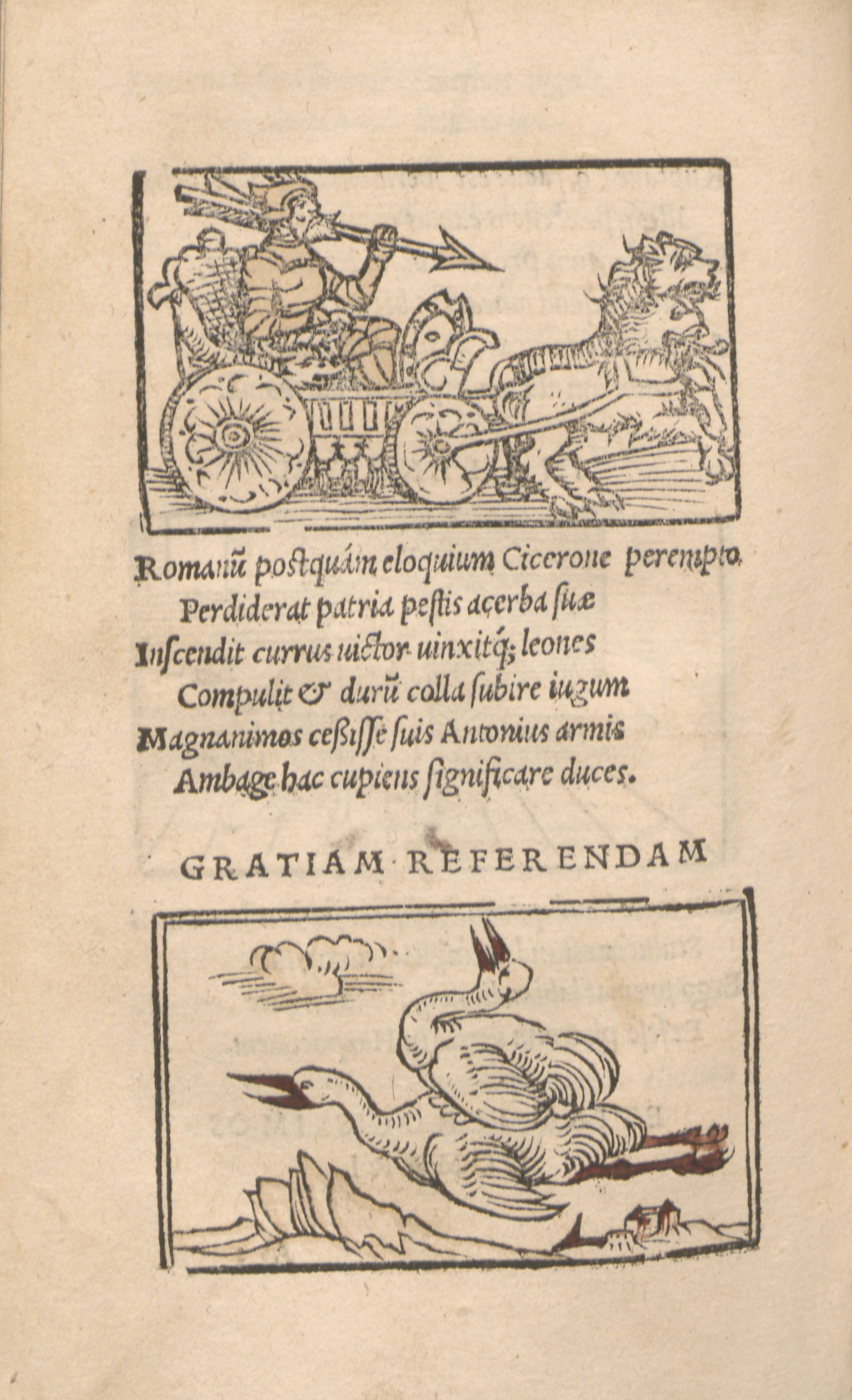

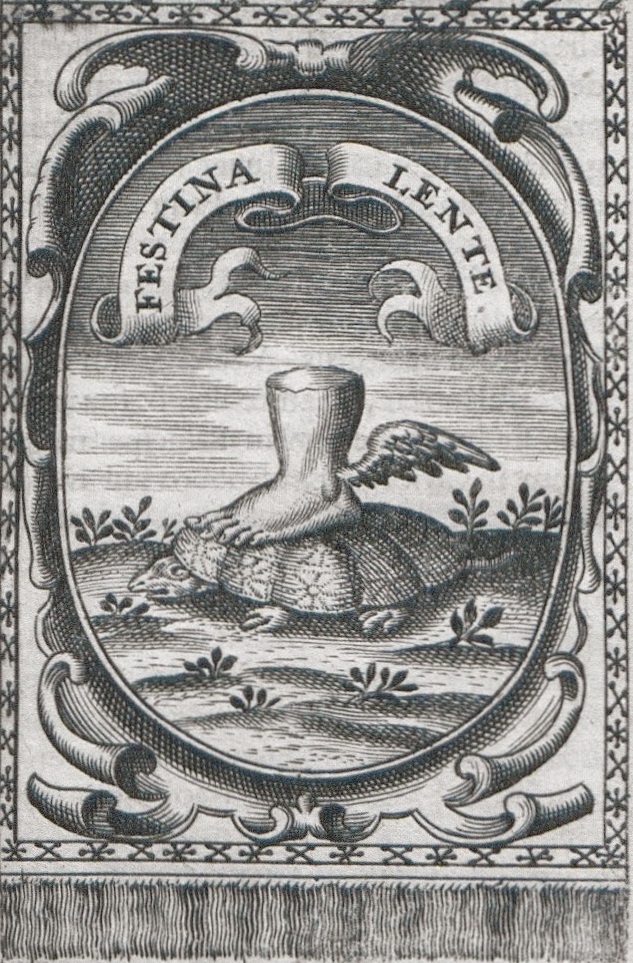

The Echo of a Voice The Ukrainian reception of emblematics (and heraldincs) is evidenced by two panegyrics devoted to Ivan Mazepa and Barlaam Jasinski, who was Jaworski’s teacher and mentor. The works demonstrate two models of Jaworski’s emblematic practice. Let us turn our attention to the first model: Echo głosu wołającego na puszczy od serdecznej refleksyj pochodzące a przy solennym powinszowaniu [...] Ianowi Mazepie hetmanowi wojsk [...] zaporoskich brzmiące głośną [...] rezonansyją (The Echo of a Voice of One Calling in the Wilderness, Coming From Heartfelt Reflection and Accompanied by Solemn Felicitation, Sounding with a Loud Resonance, to Ian Mazepa, Hetman of the Zaporizhian Host) (Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv 1689). The title alludes to the words of John the Baptist from Matthew 3:1-3, which invoke the preparation for the work of Jesus. The piece is composed of three parts: exordium – with a foreword to Ivan Mazepa in Polish, narratio – Polish poems to an escutcheon, which is constructed out the coats of arms of Mazepa’s and related families. The Mazepa coat of arms (called Kurcz) is placed in the center of the stemmat with a subscription underneath: Piękna jak jasny księżyc, jest Panna Przeczysta, (Beautiful as the bright moon is the Maiden Purest, / As she is called in Scripture by her panegyrist, / While Saint John beautifully serves as Aurora, / As he marshals for the eternal Sun of Truth. / They stand here at the Cross – for what cause? / No wonder: ‘tis where the Maiden and John have long stood.) The poem, written in Polish alexandrines, refers only to the Mazepa coat of arms (in the center: an image of a Y-shaped cross, a half-moon on the left-hand side and a six-pointed star on the right-hand side). It is not a (heraldic) description of the coat of arms, but rather its allegorical interpretation, in which the author excludes the literal sense (sensus litteralis) and instead enters the level of the allegorical (sensus allegoricus) and the moral (sensus moralis). He achieves through figural equivalences (personificatins): the moon – the Purest Maiden, and the Aurora (the star) – John (Mazepa). In this sense, the author explains the coats of arms surrounding that of Mazepa, belonging to the related families of Jasieńczyk (Key), Sas, Korczak and Odrowąż. Heraldic signs serve the author as a source of surprising concepts, associations, antytheses and comparisons[8]. The piece concludes with an eight-page elogium in Latin entitled Anacephalaiosis. The main (and the most interesting) part of the narratio are pictorial-verbal combinations, constructed out of heraldic and emblematic signs (picturae), accompanied by inscriptions. With a verbal component added, that of subscription in various forms of Polish verse and meter, they belong to the category of three-element emblems, a total of six on twenty-six pages. The rules of Jaworski’s emblematic practice in that work could be explained using two examples from the main part of the piece. The first emblem (ill. 3) shows an image of the eagle from the coat of arms of the Russian Tsardom, combined with the heraldic signs of Mazepa, held by the bird in its talons. The inspiration for this construction was emblem 22 from the collection of Saavedra[9], where a two-headed eagle holds a thunderbolt (ill. 4). Jaworski (and his engraver Szczyrski)[10] did not retain the inscription from Saavedra’s emblem, but formulated two of their own, placing them on ribbons in the eagle’s talons: to the left Suis caelum hoc illustre Planetis (“These are the glorious heavens for your Planets”), to the right Hoc fulmen in hostes („This is a thunderbolt against enemies”). In addition, the author set a third inscription under the emblem’s icon: Dum Tua Syderis sunt stemmata clare Planetis / Inde Tuam coelum quis negat esse Domum („So long as your stemmata gleam with celestial planets / Who could deny that the heavens are your Home”). The three-part structure of the emblem is secured by a subscription, written in hendecasyllable in thirty-four Sapphic stanzas, praising the acts of war and knightly-patriotic virtues of hetman Mazepa. For illustration, I present two stanzas: Niech kto chce, złoty wiek Saturna chwali, Chwal kto chcesz Pokój, ja zaś krwawe fale, (Let he who will praise the golden age of Saturn, / I – the iron age, cast from solid steel,/ I think it of far heavier weight / than golden Tags. Praise whoever will Peace, me – waves of blood, / Of the battling Bellona, if I lay them on the scale, / I see a far higher value of battle / than peace.) The engraving of the second emblem depicts Ivan Mazepa in knightly robes, riding a carriage drawn by two lions (ill. 5). The graphic model for this emblem was the visual topos of the triumphant carriage (currus triumphalis), which can be found in many emblem books. The prototype of this motif in emblematics is an icon by Alciatus (Emblematum libellus)[11]; such an emblem can also be found in Saavedra’s collection[12]. In this case, the engraver had more room for shaping a new emblem by using symbols present in the Mazepa coat of arms. Jaworski formulated an inscription (lemmata) and a subscription, spanning 126 verses. The main stylistic means used are anaphoras and syntactic parallelisms, used for the amplification of the theme of the “victorious journey” of Ivan Mazepa. The other emblems in the work are constructed the same way. The technique of projection[13] (that is, inclusion) of iconographic signs from the Mazepa coat of arms onto picturae from West European books of emblems, as a result of which new (three-part) emblems are created, follows the scheme below (excluding the text of the subscription). The collection of images reveal the reserve of iconographic patters from which Jaworski could have drawn. The technique of transforming iconographic signs of the coat of arms through projection is used by Jaworski and his engraver in the (chronologically) following panegyric work, devoted to Barlaam Jasinski on the occasion of his appointment as metropolitan in the year 1690.

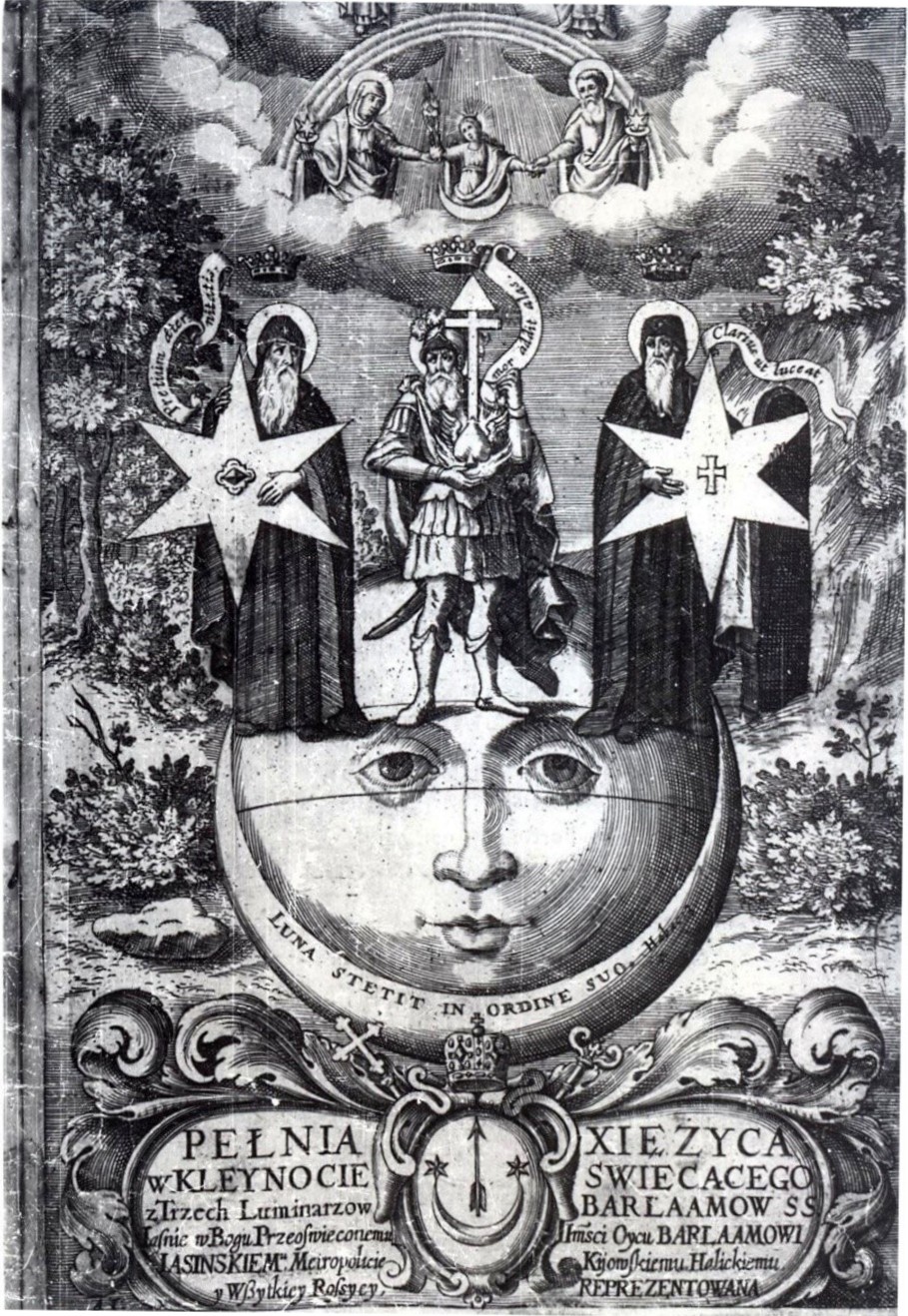

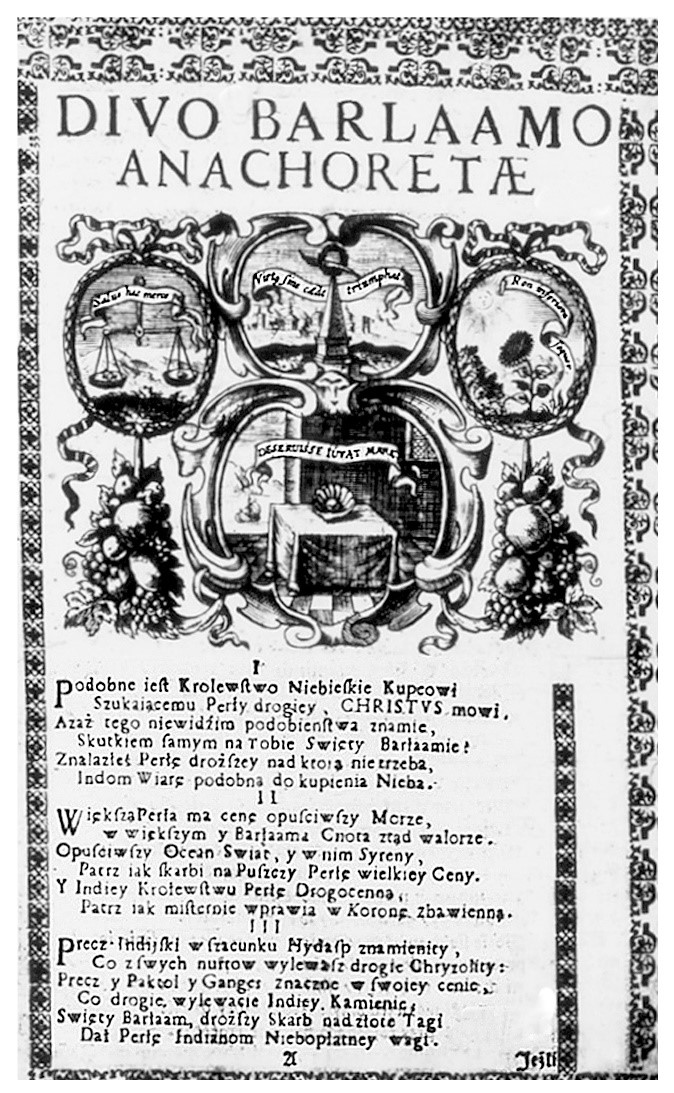

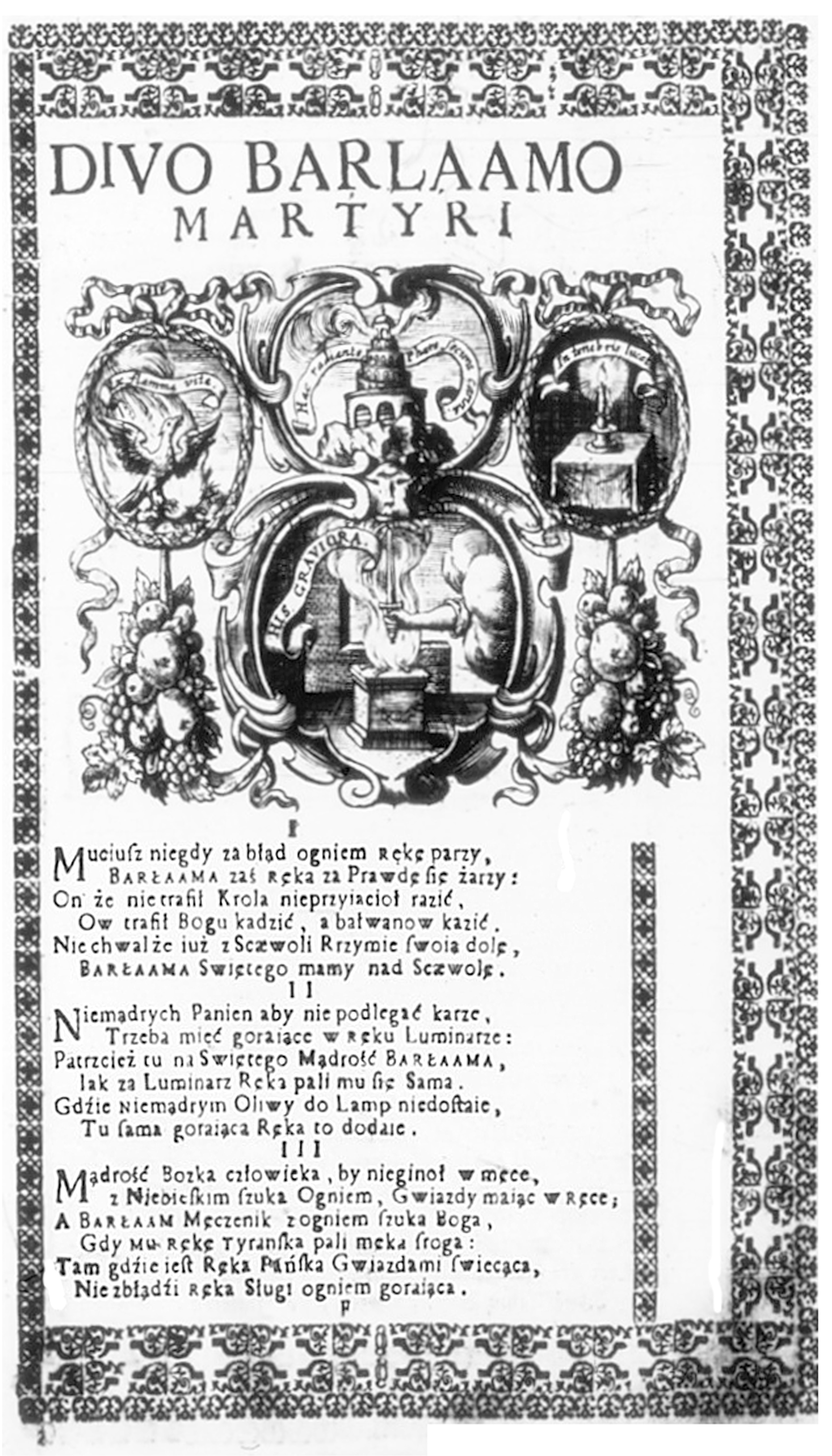

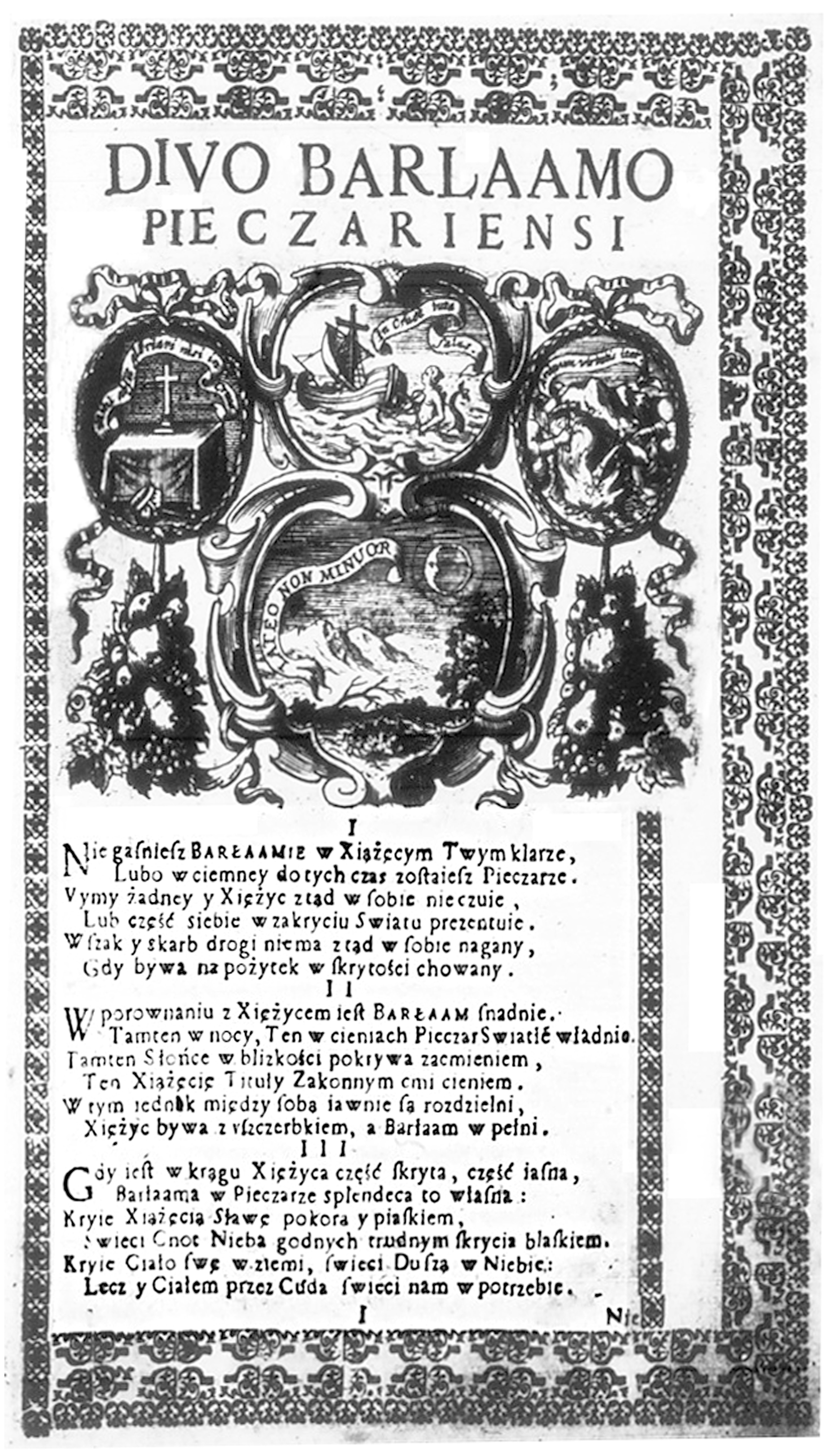

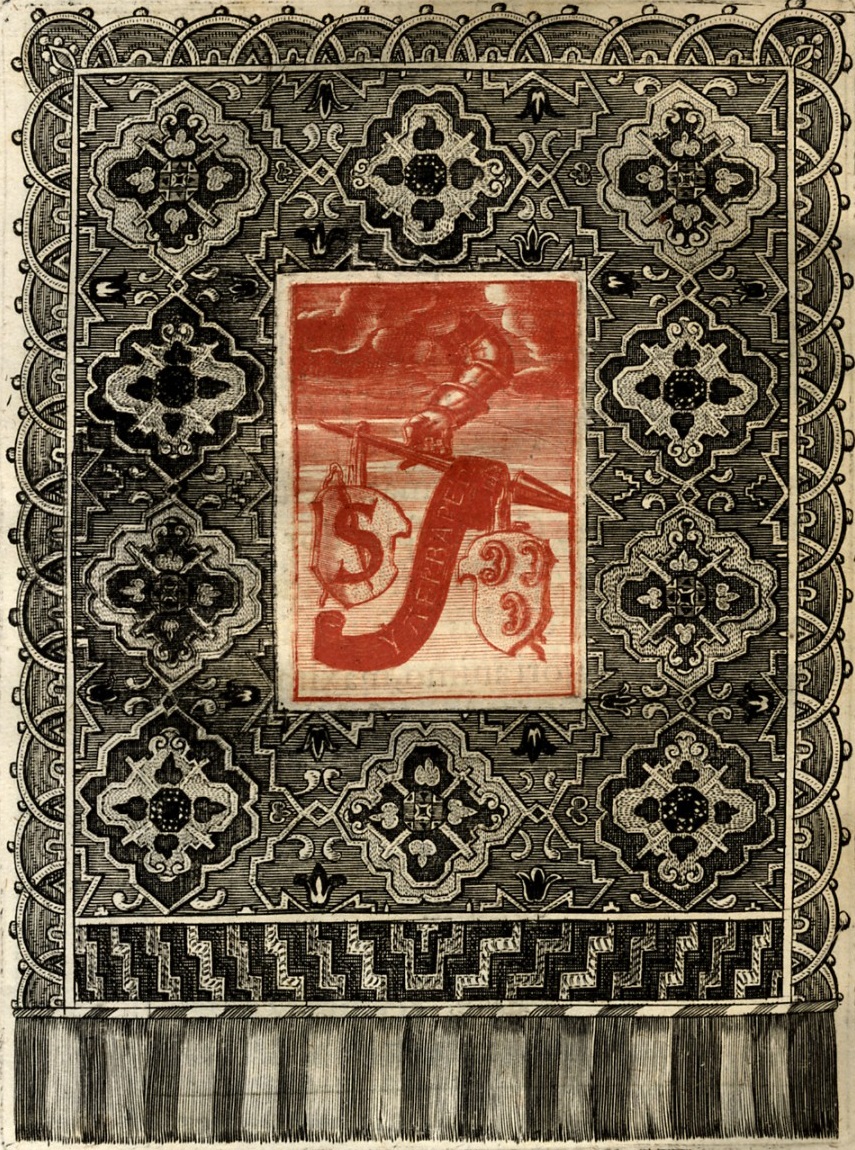

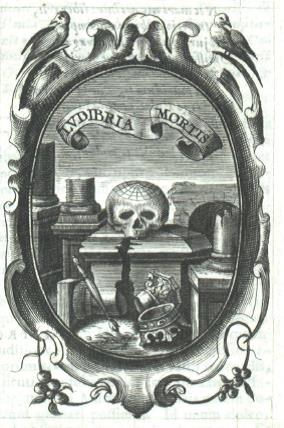

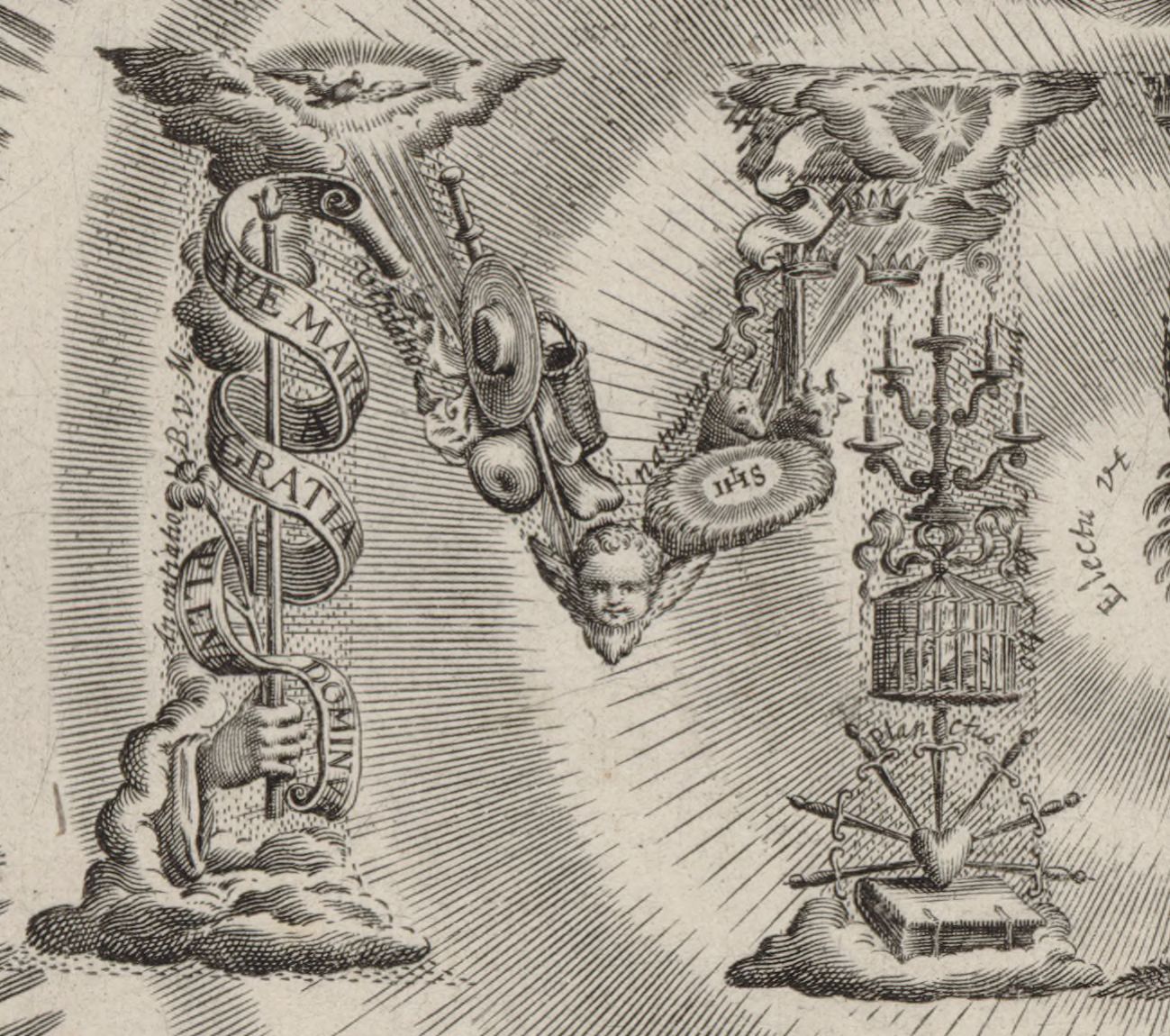

The Plenitude of Inexhaustible Glory (1691) Another example of Jaworski’s Polish-language emblematic practice is a 1691 panegyric, published in Kyiv (at the printing house of Pechersk Lavra), entitled The Plenitude of Inexhaustible Glory in the Heraldic Moon From Three Luminaries Primae Magnitudinis, Barlaam the Saint Hermit, Barlaam the Saint Martyr, Barlaam the Saint of Pechersk. The engraver hired to work on the collection was Leonidas Tarasiewicz, educated in Augsburg (ill. 8). This seventy-two-page piece consists in 1062 Polish verses (as well as Latin elogies). It is an attempt at a biographical synthesis, intended to present particular stages of the life and work of Barlaam Jasinski in pictorial-verbal combinations. The exordium alludes to the title page engraving, which is simultaneously a pictura of a newly-created emblem with inscriptions placed on ribbons. Jasinski’s coat of arms is shown twice: at the bottom in its authentic shape, while at the top – as a result of a transfiguration of the iconographic signs of the coat of arms. The face of the Mother of God is depicted on the moon, as explained by the subscription. Luna sub Pedibus Eius (Apocalypsa 12) Przeczystej Matki Bożej Miesiąc jest podnóże, (The Moon is the foothold of the Mother of God, / Next to it: two Stars and an Arrow. What is their significance? / The Star shines at night, as Faith and Hope / Only give help in the mortal life: / Faith is rightly bespoken by the First Morning Star, / As it starts the day with Faith since the rise of sin, / The Second Evening Star bespeaks Hope, / As it shines with trust at the sundown of life. / The arrow flying high is the Love for God / With it, the Moon of Humility at Mary’s feet.) The inscriptions in the emblem, through their intertextual references, signify the cosmic-biblical sphere. The words “Luna stetit in ordine suo”, printed inside the crescent moon, are a reference to the words of prophet Habakkuk: “The sun and moon stood still in their habitation: at the light of thine arrows they went, and at the shining of thy glittering spear” (Habakkuk 3:11)[14]. Three historical figures are standing on the moon: left, Saint Barlaam, holding the star from Jasinski’s coat of arms, with the inscription Pretium aeternitate (“The price of eternity”); center, Gaius Mucius Scaevola with the heraldic arrow protruding from his heart, with the inscription Amor addit alas (“Love gives wings”)[15]; right, Varlaam Pechersky (Варлаам Печерский) with the heraldic star and the inscription Clarius ut luceat (“How brightly he shines”). The narratio of the piece is also composed of three parts, recounting the lives and virtues of the three Saint Barlaams (the hermit, the martyr and the Pechersk monk), in order to commemorate and celebrate the author’s teacher and mentor once again:

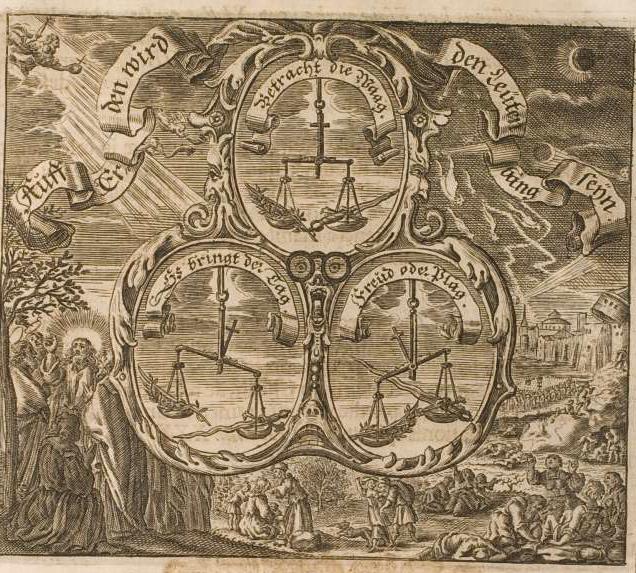

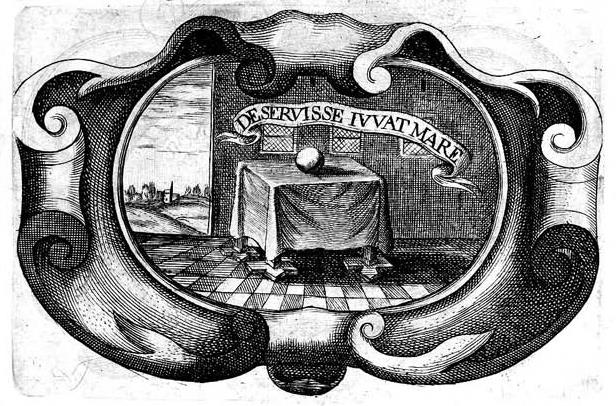

Each part is a pictorial-verbal combination, constructed on the basis of graphic patterns present in West European emblem books. In this piece, references to the German emblematic tradition can be seen specifically[16]. The technique of creating pictorial-verbal complexes was based on the authors’ and engravers’ conjunction of emblems with the same motifs or pictorial themes into one complex and adding the text of subscription. Representatives of such a technique included Franz Juliusz von dem Knesebeck, Johann Michael Dilherr and Georg Philipp Harsdörffer[17]. It differs from the most common emblematic technique of composing emblem books’ title pages by including several emblems. The technique of creating pictorial-verbal complexes was based on the authors’ and engravers’ conjunction of emblems with the same motifs or pictorial themes into one complex and adding the text of subscription [18]. Illustration 9 shows an example of such an emblematic complex from a collection by Dilherr, who collaborated with Harsdörffer (with the subscription omitted). In parts 1-3 of the narratio, Jaworski and his engraver Tarasiewicz have created complexes out of four distinct emblems. For example, into the center of the complex Divo Barlaamo Anachoretae (ill. 10) an emblem of a pearl is installed, with an inscription Deseruisse iuvat mare (“Fortunately she escaped the sea”), selected from a collection by Silvester Pietrasancta (ill. 11). Through the conjuction of the three emblem complexes (Divo Varlaamo Anachoretae – Divo Varlaamo Martyri [ill. 12] – Divo Varlaamo Pieczariensi [ill. 13]) and the intertextual references to stories and legends about the three saints in the subscriptions, an emblematic biography of Barlaam Jasinski emerges for the reader in the reading process. The conclusio of the piece contains a prose text. The author repeats and emphasizes the attributes of Jasinski’s virtues (gratitude, humility and charity) and elaborates on that theme in the final part, Mnemosyne sine recordatio patrocinii Stephanica.

Conclusion In Polish-language panegyrics by Stefan Jaworski, two models of emblematic practice can be distinguished, having arisen in collaboration with Ukrainian engravers[19]: (1) creating new emblems through the inclusion (projection) of iconographic signs of the Mazepa coat of arms in The Echo of a Voice… into emblems from Saavedra’s collection and in Arctos et antarctos… through the transformation (transfiguration) of Jasinski’s coat of arms on the title page; (2) constructing emblematic complexes in the panegyric The Plenitude of Inexhaustible Glory… out of West European emblem books (Pietrosancta, Saavedra). In his construction of pictorial-verbal combinations, Jaworski prefers a three-part structure of the emblem (inscriptio – pictura – subscriptio), However, he introduces not one, but several inscriptions to his emblems (see The Echo of a Voice…), and the poems in the subscription always span several pages (without prose commentaries). His idea of an emblem approaches Masenius’ concept of pictorial-verbal combinations, which the latter presented in his late Baroque work Speculum Imaginum Veritatis occultae. Masenius describes emblema, symbolum, hieroglyphicum et aenigmatum with an superordinate term of imagines figuratae. There, the definition of the emblem can be found: Emblema est imago figurata, ab intelligentium rerum natura ad mores vitamque rei intelligentibus uno conceptu exponendum translata[20]. What follows from this definition is that the function of the emblem is oriented towards the interpretation of the moral sense (sensus moralis), which can be extended to the interpretational level of the anagogical sense (sensus angagogicus). Such a hermeneutic understanding of the emblem was very widespread in the writers’ milieu of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, so much so that it was the subject of courses in rhetoric and poetics (emblematicae declamationes). This is confirmed not only by definitions of the emblem in Kyivan handbooks of rhetoric, but above all by the Polish-language panegyrics by Stefan Jaworski, a professor of rhetoric and poetics, as well as the emblematic works of other “unknown” Kyivan poets, such as Filip Orlyk, who was Jaworski’s student in Kyiv, Jan Ornowski and Laurentius Krszczonowicz

Translated by: Aleksandra Paszkowska

[1] The precursor of (modern) research on the Polish-language works of ekstern Slavic poets on the former territory of the Polish republic in the seventeenth century, especially writers of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy circles, was Ryszard Łużny (1927–1998). See R. Łużny, Pisarze kręgu Akademii Kijowsko-Mohylańskiej a literatura polska. Z dziejów związków kulturalnych polsko-wschodniosłowiańskich w XVII–XVIII wieku, Kraków 1966; R. Łużny, Stefan Jaworski – poeta nieznany, in: „Slavia Orientalis” (1967), no. 16, pp. 363–376; R. Łużny, Twórczość Stefana Jaworskiego – poety ukraińsko-rosyjsko-polskiego czyli raz jeszcze o baroku wschodniosłowiańskim, w: Języki wschodniosłowiańskie. Materiały Ogólnopolskiej Konferencji Naukowej, Łódź 1979, pp. 103–114; W. Kroll, Heraldische Dichtung bei den Slaven. Mit einer Bibliographie zur Rezeption der Heraldik und Emblematik bei den Slaven (16.–18. Jahrhundert), Wiesbaden 1986. Łużny’s stipulations guided the works of his student Rostysław Radyszews’ki: R. Radyszews’kyj, Polskojęzyczna poezja ukraińska od końca XVI do początku XVIII wieku. Część I: Monografia. Kraków 1996; and an anthology – Roksolański parnas. Polskojęzyczna poezja ukraińska od końca XVI do początku XVIII wieku. Część II, ed. R. Radyszews’kyj, Kraków 1998. See also Giovanna Brogi Bercoff, Stefana Jaworskiego poezja polskojęzyczna, in: Contributi italiani al XII Congresso Internazionale degli Slavisti (Cracovia 26 Agosto – 3 Settembre 1998), Hg. F. Esvan, Napoli 1998, pp. 349–353. [2] Ф. А. Терновский, Митрополит Стефан Яворский. Биографический очерк, w: Труды Киевской духовной академии, Киев 1864, t. 1, p. 57. [3] See Catalogus librorum Stephani Jaworski, metropolitae Riazanensis et Muromensis, conscriptorum anno Domini 1721 mense Augusto, cum ex Divina gratia morbo pulsante sentiret se morti vicinum, in: С.И. Маслов: Библиотека Стефана Яворского. Киев 1914, pp. V–LV (Приложения). [4] See Д. Чижевський, Фільософія Г. С. Сковороди, Warszawa 1934; Д. Чижевський, Український літературний барок. Нариси. Частина третя, Прага 1944. See W. Kroll, Dmitrij Tschižewskij und die Emblematik. Versuch einer Rekonstruktion, w: D.I. Tschižewskij, Impulse eines Philologen und Philosophen für eine komparative Geistesgeschicht, Hg. A. Richter, B. Klosterberg. Berlin 2009, pp. 61–84; ibid. the bibliographic of his works on emblematics. New editions of the aforementioned works by D. Czyżewski, edited by Leonid Uszkałow, are also available on the Internet:: http://litopys.org.ua/chysk/chysk.htm. [5] For the bibliographic description see P. Buchwald Pelcowa, Emblematy w drukach polskich i Polski dotyczących XVI–XVIII wieku. Bibliografia, Wrocław–Warszawa–Kraków–Gdańsk–Łódź 1981, pp. 101–102; Я. Запаско, Я. Исаевич, Памятники книжного мистецтва. Каталог стародруків, виданих на Україні. Книга перша (1574–1700), Львів 1981. [6] See Д. В. Степовик, Леонтій Тарасевич і українське мистецтво барокко, Київ 1986. [7] This was noticed by Ryszard Łużny, Stefan Jaworski – poeta nieznany, op. cit.., p. 372. See M.C. Sarbievii, Lyricorum libri IV, Antverpiae 1634, pp. 116–117 (http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de); this exact edition was found in Jaworski’s library (see Маслов, op. cit., no. 587). [8] R. Radyszews’kyj, op. cit.., p. 227; B. Bergcoff, op. cit., pp. 353–354. [9] D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Idea de un príncipe político cristiano, Amstelodami 1659, no. 22. See Emblemata. Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVIII. Jahrhunderts, hrsg. von A. Henkel, A. Schöne, Stuttgart 1976, p. 762. [10] Jaworski’s collaboration with engravers is described by Smytro Stepovyk (see footnote 7 and 21). [11] Zob. Emblemata. Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst, dz. cyt., s. 385–386; wszystkie wersje z książek Alcatiusa można porównać w Internecie: http://emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/alciato/emblem.php?id=A56a004. [12] D. de Saavedra Fajardo, Idea principis christiano-politici [...], Bruxellae 1649, nr. 64. [13] See A. Hansen-Löve, Intermedialität und Intertextualität. Probleme der Korrelation von Wort- und Bildkunst. Am Beispiel der russischen Moderne, w: Dialog der Texte. Hamburger Kolloquium zur Intertextualität, Hg. W. Schmid und W.D. Stempel, Wien 1983, p. 304; A. Hansen-Löve distinguishes three differend methods of transforming verbal signs (Wort-Zeichen) and pictorial signs (Bild-Zeichen): 1. Transposition, 2. Transfiguration, 3. Projection. [14] Translator’s note: biblical quotes after King James Bible. [15] The inscription is a paraphrase of Psalms 55:6 „et dixi quis dabit mihi pinnas sicut columbae et volabo et requiescam (“And I said, Oh that I had wings like a dove! for then would I fly away, and be at rest”); it also appears in emblem books owned by Jaworski: Vaenius, Amorum emblemata, Antverpiae 1612, pp. 114–115 (Amor addit inertibus alas) and H. Hugo, Pia desideria, Antwerpen 1624, emblem 43 (http://emblems.let.uu.nl). [16] See I. Höpel, Das mehrständige Emblem: zu Geschichte und Erscheinungsform eines seltenen Emblemtyps, in: The Emblem in Renaissance and Baroque Europe. Tradition and Variety. Selected papers of the Glasgow International Emblem Conference, 13–17 August 1990, ed. by A. Adams, Leiden–New York–Köln 1992, pp. 104–117. [17] For the context of that technique, see I. Höpel, op. cit.; I. Höpel, Harsdörffers Theorie und Praxis des dreiständigen Emblems, in: G.P. Harsdörffer, Ein deutscher Dichter und europäischer Gelehrter, hrsg. J.M. Battaforano, Berlin 1991, pp. 195–234; D. Peil, Nachwort, in: J.M. Dillherr, G.P. Harsdörffer, Dreiständige Sonn und Festtag Emblemata oder Sinn Bilder, hrsg. D. Peil. Hildesheim–Zürich–New York, pp. 1–28. [18] G.Ph. Harsdörffer allows the composition of two to six emblems. See G.P. Harsdörffer, Frauenzimmer Gesprechspiele. Sechter Theil [...], Nürnberg 1646, p. 293 (http://diglib.hab.de/show_image.php?dir=drucke/lo-2622-6&pointer 483). [19] See Д. Степовик, Українська гравюра бароко: Майстер Ілля, Олександр Тарасевич, Леонтій Тарасевич, Іван Щирський, Київ 2012. I. Szczyrski, L. Tarasiewicz and O. Tarasiewicz were educated in the art of engraving in the Kilian family printing house in Augsburg among others. [20] J. Masen, Speculum Imaginum Veritatis occultae, Coloniae 1681, p. 656 (first ed. 1651). The definition of the emblem is repeated in the rhetorics of the Kiev-Mohyla Academy. In his overview of these handwritten and printed sources, V.P. Masljuk cites that definition (without an author noted in the manuscript). See В. П. Маслюк, Латиномовні поетики і риторики XVII–першої половини XVIII ст. Та їх роль у розвитку теорії літератури на Україні, Київ 1983, p. 177; see also T. Michałowska, Staropolska teoria genologiczna, Wrocław–Warszawa–Kraków–Gdańsk 1974, p. 139, pp. 168–169. On the lexical ambiguity of the term „emblem”, see also M. Górska, Ut pictura emblema? Teoria i praktyka, in: Ut pictura poesis / ut poesis pictura. O związkach literatury i sztuk wizualnych od XVI do XVIII wieku, ed. A. Bielak, Warszawa 2013, pp. 31–46. |

Ill. 1. Stefan Jaworoski, Arctos et antarctos caeli Rossiaci in gentilibus syderibus [...] Barlaami Jasinski Kijoviensis Haliciensis totigq. Rossiae orthodoxi archiepiscopi metropolitae (Ławra Pieczerska, Kijów 1690) Ill. 3. Stefan Jaworski, Echo głosu wołającego na puszczy od serdecznej refleksyj pochodzące [...], Kijów 1689.

Ill. 7. Diego de Saavedra Fajardo, Idea principis christiano-politici [...], Bruxellae 1649, nr 64.

Ill. 8. Stefan Jaworski, Pełnia nieubywiącej chwały [...], Kijów 1691 (frontyspis).

Ill. 9. M. Dilheer, Heilige Sonn – und Festtags-Arbeit/ Das ist: Deutliche Erklärung Der jährlichenSonn– und Festtäglichen Johann Evangelien [...], Nürnberg 1674, s. 16. (http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/c-321-2f-helmst/start.htm).

Ill. 12. Stefan Jaworski, Pełnia nieubywiącej chwały [...], Kijów 1692, Divo Barlaamo Martyrii.

|

MACIEJ WIECZOREK

TOMASZ TRETER IN VIEW OF THE ENGRAVING WORKS OF CORNELIS CORT

|

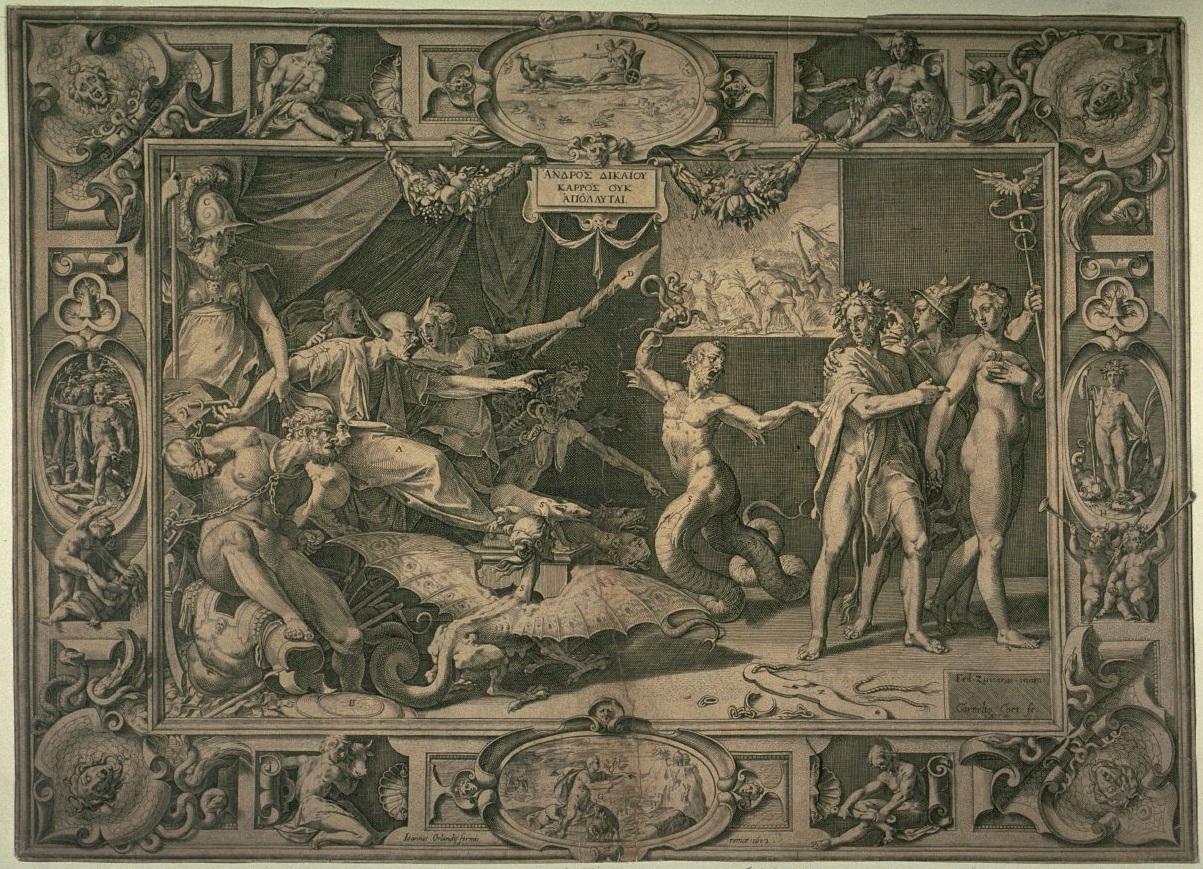

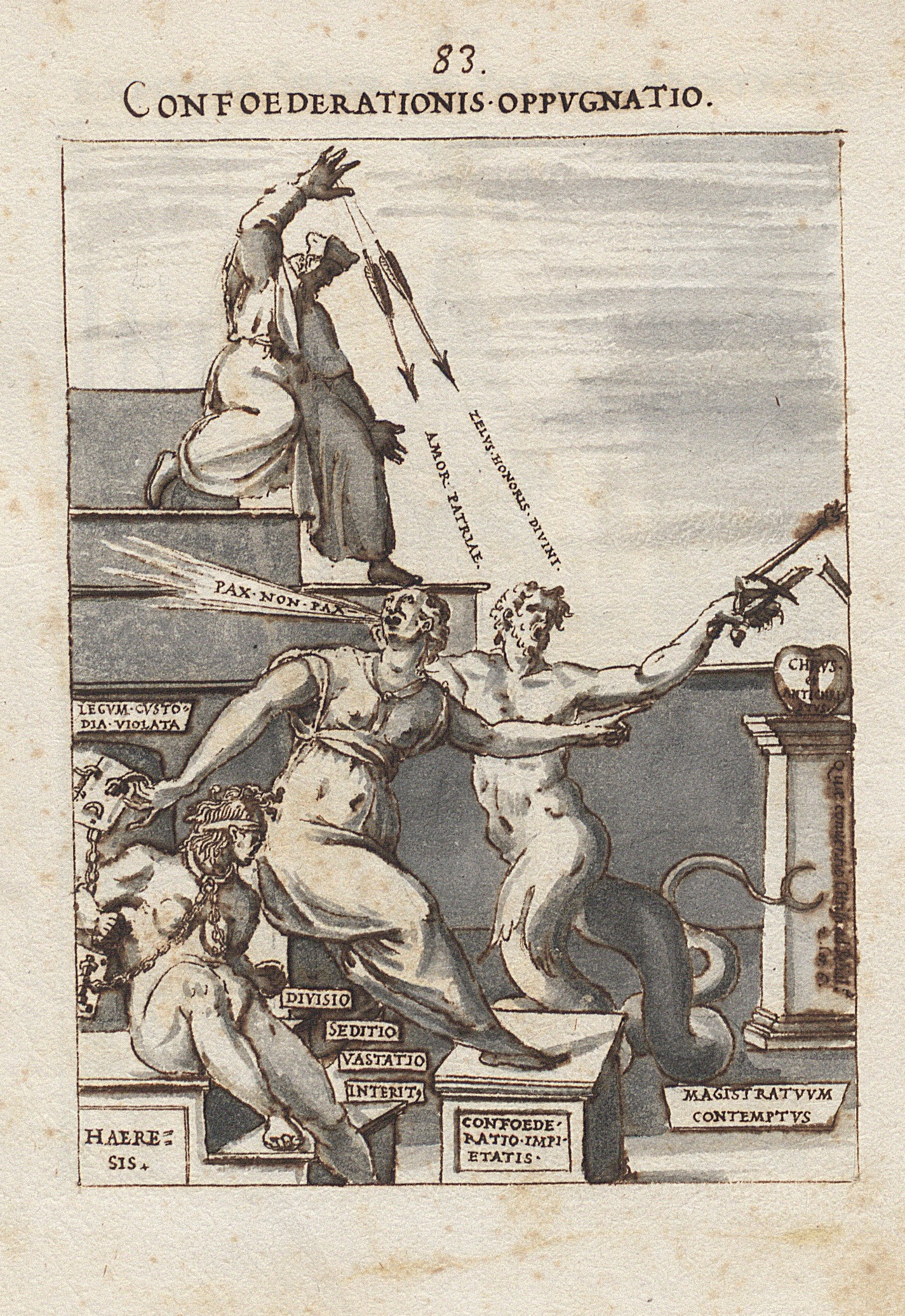

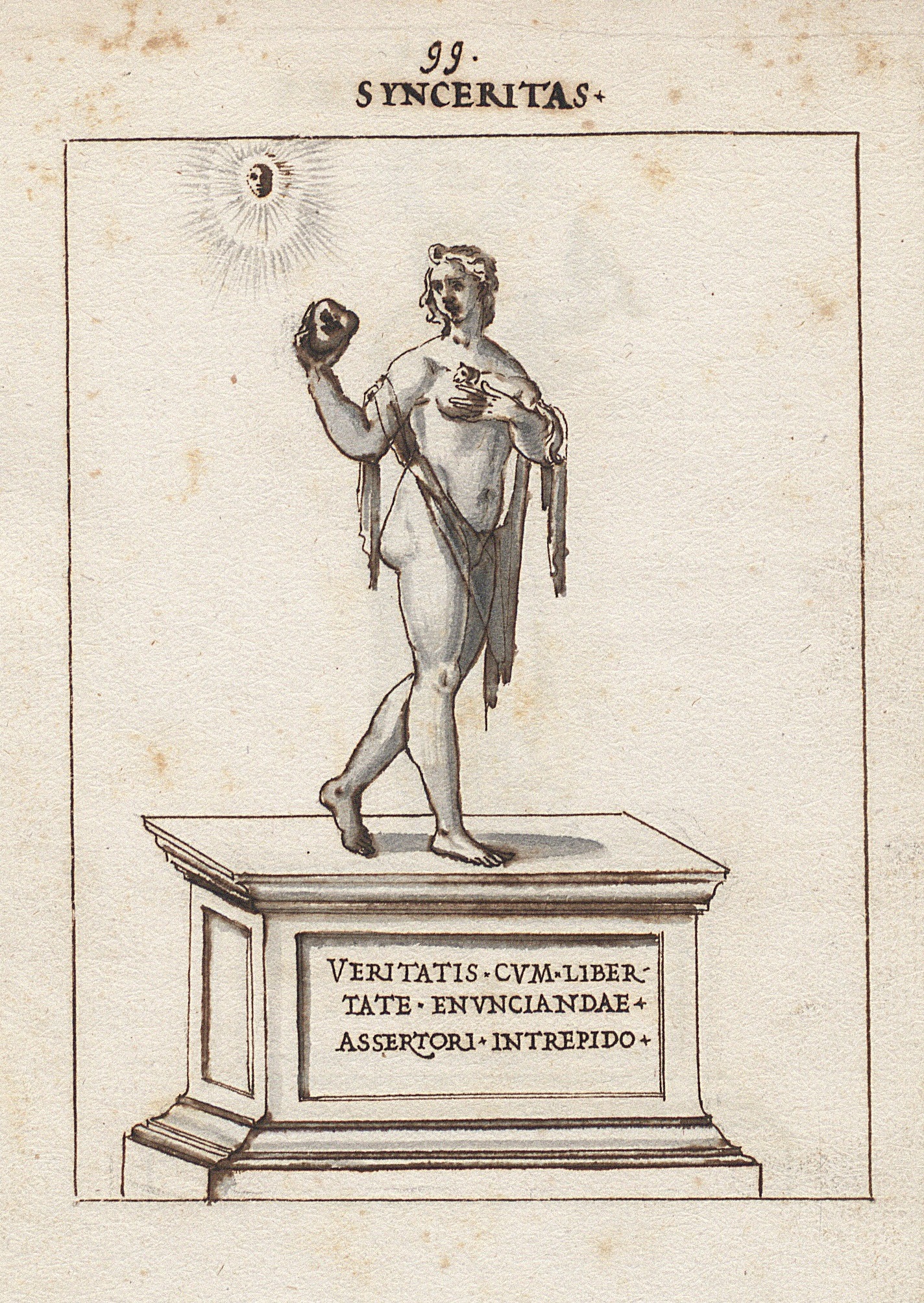

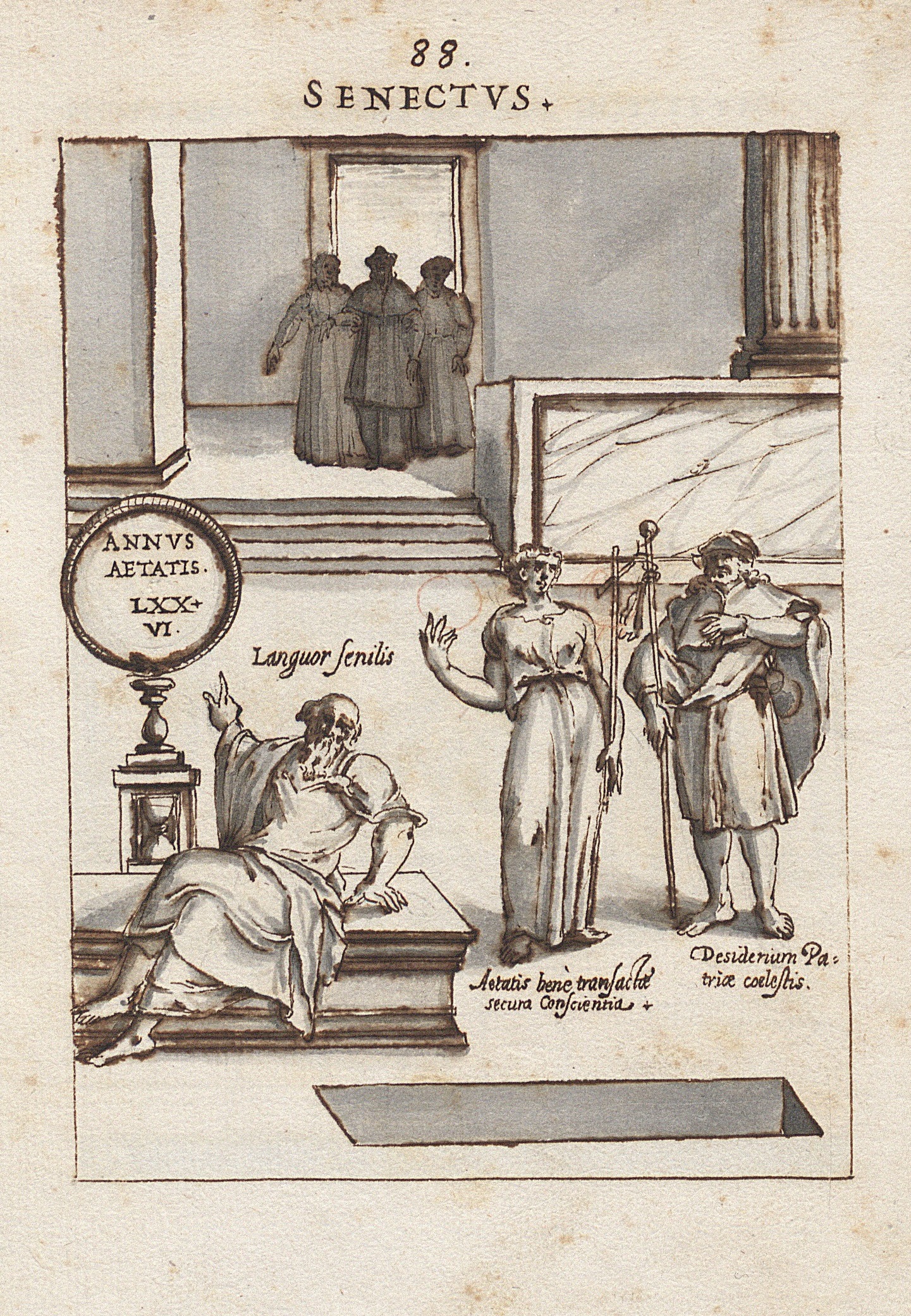

A collection of Tomasz Treter’s drawings[1], stored in the Department of Manuscripts of the National Library of Poland, is an item of unique value. It is a tentative sketchbook for the cycle of emblematic copperplates entitled Theatrum virtutum ac meritorum D. Stanislai Hosii…, devoted to cardinal Stanislau Hosius[2]. It is also a rare sixteenth-century case in Polish art history in which finished graphic artwork was preceded by a preparatory, drawn concept. The uniqueness of the collection is amplified by its unusual authorship. Born in an impoverished family of burghers from Chwaliszewo, a city then separate from Poznan, Tomasz Treter (1547–1610) was not a professional engraver[3]. Instead, this clergyman and Doctor of Law, alum of the Jesuit school in Braniewo, was a close associate of Stanislaus Hosius, Andrzej Batory and Anna Jagiellonka[4]. He resided in Rome in the years 1569–84 and 1586–93[5]. The drawings in question were created during his first sojourn in the Eternal City. Art historian Tadeusz Chrzanowski assumes that Treter began working on his drawings as early as 1579, immediately following Hosius’ death, and completed the cycle in 1580 or soon after[6]. On the other hand, Grażyna Jurkowlaniec has extended the timeframe of the manuscript’s creation, dating its execution between August 1579 and August 1582[7]. The subject of Theatrum virtutum… has already been discussed in a number of publications[8]. However, they lack an exhaustive analysis of the collection itself in the context of its artistic debt to works of renowned Roman artists of the last quarter of the sixteenth century[9]. It is beyond any doubt that Treter, as a non-professional artist, was simply forced to draw inspiration and compositional patterns from other creators, in this case engravers in specifically. The mere intention of publishing the drawings as copperplates must have determined the field of artistic influence to a certain degree. This paper could by no means accommodate a thorough examination of all Treter’s emblems in relation to his contemporary graphic production. Here, I would like to analyze Treter’s drawings with respect to their relationship to the works of one engraver: Cornelis Cort. Cort (1533–1578) was among the most valued sixteenth-century engravers[10]. Beginning in 1565, his activity is documented in Venice, and starting in 1567, he strived to publish his pieces in Rome[11]. No doubt remains, then, that during his stay in the Eternal City, Treter had contact with Cort’s engravings circulating there[12]. Indeed, one can find references to the compositions of Cornelis Cort’s five copperplates: The Adoration of the Holy Trinity, The Birth of Mary, Calumny of Apelles, The The Practitioners of the Visual Arts and Saint Roch in the sketchbook for Theatrum virtutum…. The Adoration of the Holy Trinity (ill. 1), based on a painting by Titian, is dated to the year 1566[13]. Cort’s composition depicts the Holy Trinity surrounded by angels in the heavens: the throning Jesus Christ, Father God, and a white dove above them. In the lower part of the composition, Old Testament prophets are placed alongside the Church’s saints, immersed in adoration. It is the pose of one of these figures that Treter used in his drawing for his emblem number 44[14], entitled Confutatio Prolegomenon Brentii (ill. 2). The heretic Johann Brenz, portrayed in that illustration, was given the pose of the reclining Moses from Cort’s engraving. Only the folds of Moses’ robes and his attributes were slightly modified: two books took the place of the Tables of the Law. Otherwise, the figure of the prophet was copied by Treter fairly faithfully. Cort engraved The Birth of Mary (ill. 3), dated to 1568[15], after a drawing by Federico Zuccaro, which was likely based on a lost composition by Taddeo Zuccaro[16]. In the foreground of the composition, the new-born Mary is depicted, tended to by nurses and angels. In the background, a bed with a resting Saint Anne adds a horizontal counterpoint to the composition. Treter employed some components of the foreground of The Birth of Mary in drawing 14 of his cycle, entitled Doctoratus[17] (ill. 4). Two allegorical figures, representing jurisprudence and sitting on both sides of cardinal Hosius, have been modeled on Mary’s nurses as drawn by Cort. In addition, Treter based his design for emblem 28, entitled Sigismundi. I. Regis. Testamentum[18] (ill. 5), on the composition of the background in Cort’s drawing. The bed along with the figure of Saint Anne was entirely copied by Treter. All components have been replicated in minute detail. Even the draping of curtains was faithfully drawn according to the original. Only the face of the female saint has been changed into the physiognomy of Sigismund I the Old, and the figure of his son, Sigismund II Augustus, was added to the right. Cort’s Calumny of Apelles, dated to 1572[19], was also engraved after a composition by Federico Zuccaro. In his work, the younger Zuccaro brother adopted a common Renaissance theme of the lost painting by Apelles. On the right-hand side of the composition, the Hero can be seen, holding Innocence by the hand. Innocence is depicted as a nude woman carrying an ermine. The two figures are being protected from calumny by Mercury. To the left-hand side, a group of “villains” is shown. King Midas with donkey years listens to the whispers of Suspicion and Calumny. He points at the Hero with his left hand, while trying to release Rage from its shackles with his right, from which the goddess Athena is stopping him. Around the figures, the artist has placed a number of grotesque creatures, human-animal hybrids. Treter used components of this complex piece in two of his emblems. Emblem 83 entitled Confederationis opugnato[20] (ill. 7) is based on the group of “villains” as drawn by Cort. The sitting silhouette of Midas was replaced with a female personification of the Warsaw Confederation. Rage, shackled to a rock, was drawn as a Gorgon and personifies Heresy, whereas the merman-like snake-legged monster represents the Devil. The monstrous figure was fairly accurately copied by Treter, who changed the positioning of its arms and added two attributes: a broken sword and a scepter. The female figure of Innocence, leading the Hero by the hand on the right-hand side of Cort’s Calumny of Apelles, found its way to Treter’s drawing 99, entitled Synceritas[21] (ill. 8). Innocence, adapted as Sincerity, has retained its original attribute – the ermine, held in the left hand. However, the figure’s right hand is raised to the face and holding a heart. In addition, a gauzy veil has been draped over the naked body. The next engraving in chronological order is The Practitioners of the Visual Arts (ill. 9), created in 1578 based on a drawing by Jan van der Straet[22]. Through its depiction of artists in a workshop, the scene presents a range of fine arts, including printmaking, anatomy, wall painting, monumental sculpture and others. It is the latter representation, called “Statuatoria”, which became a model for Treter’s first, opening emblem – Patria et Natalis dies[23] (ill. 10). In Cort’s engraving, a sculptor can be seen, chiseling a statue of Rome in marble. The goddess is holding a small figurine of Victory in her right hand, raised to eye level, and a scepter in her left hand, resting on her knee. At her feet, a bearded man reposes, personifying the river Tiber, along with a she-wolf nursing Romulus and Remus. In his own design, Treter transformed Rome into Cracovia and Tiber into Vistula. The composition was replicated to be almost identical. Only some attributes have been added: a model of the city in the goddess’ right hand, a crown on her helmet and the coat-of-arms of the city of Krakow in place of the she-wolf. Treter referred to Cort’s Practitioners… in one more of his drawings. Far from being a reference strictly speaking, a fragment of the more advanced artist’s composition was used as a drawing prop. In emblem 15 Benedictio paterna[24] (ill.11), Treter copied the positioning of the sitting engraver’s legs from the lower left-hand corner of Cort’s piece. The Polish artist duplicated the contour of the table, the legs, robes and the stool on which Cort’s engraver is sitting. The last engraving of Cornelius Cort emulated by Tomasz Treter is the depiction of Saint Roch. Cort’s engraving, based on a composition by Hans Speckaert, was first printed in 1577[25]. The standing silhouette of the saint in pilgrim’s robes was copied in emblem 88 of Treter’s cycle, entitled Senectus[26] (ill. 13). Saint Roch became a model for a figure personifying the longing for a home in heaven. One can easily note that Treter referred directly to a copy of Cort’s engraving, made in 1580 by Agostino Carracci (ill. 12), as the altered composition would suggest[27]. It is clear that Tomasz Treter knew Cornelis Cort’s engraving work very well. In his drawings, the Polish canon referred to engravings published over the course of 25 years. This means that Treter followed Cort’s artistic development and even must have owned the Dutchman’s graphic works. What other conclusions can one draw from the observations above? First, that the dating of Treter’s drawings needs revisiting. As mentioned above, Tadeusz Chrzanowski in his monograph on Treter dateed the creation of the sketches to directly after Hosius’ death, that is, as soon as 1579[28]. However, the most recent engraving on which Treter based his drawings was not published until 1580[29]. On that basis, the lower limit of dating Treter’s cycle should not exceed the year 1580. What is more, new light is shed on Treter’s artistic taste. So far, the artist has been described as a collector of emblems, sententiae and polonica in the form of images of Polish saints and rulers[30]. Yet, as proven in this paper, Treter also displayed a penchant for works of very high artistic value. As argued above, the engravings which are the subject of this article must have been in possession of the clergyman, and thus can give the researcher a clearer vision of the scope of Treter’s collection. In addition, it becomes undeniable that through his collection, Treter knew the works of such artists as Titian, Jan van der Straet or the Zuccaro brothers. The creations of the brother, Federico, had a significant presence in the Roman milieu of the late 1500s[31]. One could therefore speculate about the orbit of artistic influence in which Treter found himself. Yet, besides the Pole’s relations with Giovanni Battista de’ Cavalieri[32] and his collaborators, or mentions of engravings by Giulio Bonasone[33] and Adamo Scultori[34], only Treter’s inspiration by Niccolo Carcignani’s[35] frescos has been discussed so far. On the basis of the juxtaposition of engravings and drawings presented in this paper, Tomasz Treter’s mode of working can also be defined to a certain degree. The several examples given demonstrate that he created his drawings based on other artists’ compositions. At times, he transposed entire arrangements of figures, at other times – only selected components[36]. However, in any case, Treter copied existing patterns in a literal manner, rather than being inspired by others’ works indirectly. The most obvious example of such a modus operandi is his duplication of the banal fragment of a table and the leg of the man sitting at it. In the light of these facts, Tomasz Treter cannot be considered as an independent artist[37]. Rather, he seems to be a dilettante who engages in artistic activities on the margin of his primary duties[38]. Therefore, it is worth to reconsider the attribution of some key art pieces to him, including the tomb of Stanislaus Hosius in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere[39], the design for the fresco of the Council of Trent in the Altemps Chapel at the same basilica[40], or the tomb of Bona Sforza in the Basilica of St. Nicholas in Bari[41]. Indeed, one can assume that Treter could have influenced the intellectual program of these realizations. However, in the light of the observations above, it seems doubtful that the Polish artist also authored their visual realization. Tomasz Treter, a dilettante, constructor of eclectic arrangements out of others’ components – this is the vision of the artist suggested by the diagnoses above. Still, his dilettantism is of extraordinary interest to the researcher. Apart from the fact that Treter is likely the first known example of a Polish amateur artist, the erudite character of his art opens up a new scope of research. From this viewpoint, the sketchbook for Theatrum virtutum… reveals itself to be a collection of fragments drawn from other artists’ compositions with which the Polish canon came in contact. Identifying these motifs would provide information on artworks to which Tomasz Treter referred directly. On such basis, an attempt at a reconstruction of the Treterian library could be made, and the notion of the artistic taste of the Polish humanists could be revised. Unfortunately, written sources give a very modest image of this, both in the case of Tomasz Treter[42] and his fellow countrymen[43]. Undertaking extensive research on the designs for Theatrum virtutum… stored at the National Library of Poland could surely shed more light on the question of art reception in the age of the Polish Renaissance.

Translated by: Aleksandra Paszkowska

[1] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130. [2] T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna Tomasza Tretera, Warszawa 1984, pp. 91–92. [3] Bibliografia Literatury Polskiej – Nowy Korbut, t. 3 Piśmiennictwo Staropolskiej, ed. R. Pollak, Warszawa 1965, pp. 345–347. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. [6] Moreover, relying on Reszko’s letter to Kromer dated August 11th, 1582, Chrzanowski indicates that the drawings must have been ready then. T. Chrzanowski, op. cit., p. 97. [7] G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość Rycin. Rzymska twórczość Tomasza Tretera i jej europejskie oddziaływanie, Warszawa 2017, p. 248. [8] K. Beyer, Rysunki oryginalne Tomasza Tretera kanonika warmińskiego z drugiej połowy XVI w., offprint, Warszawa 1868; J. Umiński, Zapominany rysownik i rytownik polski XVI w., ks. Tomasz Treter i jego „Theatrum virtutum D. Stanislai Hostii”, „Collectanea Theologica” 1932, pp. 13–59, here pp. 44–58; T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna…, pp. 91–108. M. Górska, Polonia – Respublica – Patria. Personifikacja Polski w sztuce XVI–XVIII wieku, Wrocław 2005, pp. 178–180; J. Talbierska, Grafika XVII wieku w Polsce. Funkcje, ośrodki, artyści, dzieła, Warszawa 2011, pp. 107–108; G.Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin..., pp. 242–254. [9] So far, only several of Treter’s drawings have been analyzed with regard to their dependence on other works of art: Chrzanowski has analyzed compositions 50, 62 and 82 – T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna..., pp. 72–74, 130–133; Górska has defined the entire collection as inspired by the engravings of Giulio Bonasone, which illustrate Achille Bocchi’s Symbolicarum questionum, de Universo genere, quas serio ludebat, libri quinque, published in Bologna in 1555 and in 1574 – M. Górska, Polonia – Respublica – Patria…, p. 179, footnote 14; Jurkowlaniec has analyzed the Frontispiece, the portrait of Hosius and compositions 1, 50, 62, 69 and 82; she revised the conclusions drawn by Chrzanowski, maintained the opinion of Górska (referring to the portrait of Hosius), indicated the influence of engravings by A. Scultori after Buonarotti (frontispiece, composition 69), of C. Cort’s engraving created after the drawing of Jan van der Straet (composition 1) as well as of the graphic cycle Seculum Romanae magnificentiae – G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość Rycin…, pp. 248–253. [10] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 1, Rotterdam 2000, p. XIII. [11] Ibid., p. XV–XVI. [12] Jurkowlaniec has indicated the dependence of the drawn composition Patria et Natalis dies (ill. 10) on the engraving by Cort The Practitioners of the Visual Arts (ill. 9); G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, s. 252. [13] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 40. [14] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 52 verso. [15] Ibid. [16] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, s. 80. [17] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 22 verso. [18] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 36 verso. [19] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 3, Rotterdam 2000, p. 126. [20] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 91 verso. [21] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 107 verso. [22] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 3, Rotterdam 2000, p. 119. [23] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 5 verso. [24] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 23 verso; see: footnote 12. [25] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 205 [26] Warsaw, The National Library of Poland, Rps BOZ 130, page 96 verso. [27] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 205 [28] T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna…, pp. 91–92. [29] M. Sellink, Cornelis Cort, P. 2, Rotterdam 2000, p. 205 [30] T. Chrzanowski, Uwagi o intelektualiście-kolekcjonerze w Polsce na przełomie renesansu i baroku, in: Mecenas, kolekcjoner, odbiorca. Materiały Sesji Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki, Katowice, November 1981, Warszawa 1984, pp. 121–145, here p. 144. [31] A. Blunt, Artistic Theory in Italy 1450-1600, Oxford 1940, pp. 138–147. [32] J. Umiński, Zapominany rysownik…, p. 24–26; J. Hess, Note Manciniane, „Munchener Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst”, v. 19, 1969, p. 114; T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna…, pp. 68–74; J. Talbierska, Grafika XVII wieku…, pp. 104–106, 108, 218; G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, pp. 213–226. [33] See: footnote 9. [34] Ibid. [35] Hess also writes about evident inspirations by the works of Circignani in the case of two easel paintings by Treter – J. Hess, Note Manciniane…, p. 111; Chrzanowski assumes Hess’s conviction and in a way extends it to the entire works of Treter, making him an imitator of Circignani’s – T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna… pp. 71, 127–128, 152; Talbierska maintains Chrzanowski’s opinion – J. Talbierska, Grafika, XVII wieku…, p. 104; Jurkowlaniec stresses the inspiration by Circignani’s works in the case of the aforementioned easel paintings, but does not define him as an imitator – G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, pp. 290, 291. [36] This is further indicated by the observations of Jurkowlaniec, see: ibid., pp. 248–252. [37] Jurkowlaniec, discussing the drawing Censura de haereticorum censura as an example, concludes that despite Treter’s frequent use of finished compositions, the designer tried to creatively adapt popular motifs. To my mind, however, absolute certainty can only be attained through the examination of Censura… with respect to contemporary graphic patterns available to Treter. Moreover, it seems unlikely that the figures of prisoners of war in that composition were modeled on the ignudi from Adamo Scultori’s engravings; ibid., pp. 252–254. [38] See: T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna… p. 147, footnote 52. In one footnote Chrzanowski characterizes Treter as a dilettante who imitates and borrows in order to facilitate his work. Yet, this remark was not elaborated upon. Further, it was only made in reference to frescos supposedly designed by Tomasz Treter and painted by Pasquale Cati, see ibid. pp. 129–130. [39] T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna… pp. 87–91. [40] Both Chrzanowski and Jurkowlaniec claim that the model for the composition of Pasquale Cati’s fresco was engraving 58 from the cycle Theatrum virtutum… . The direction of inspiration is, to my mind, disputable and needs a more thorough examination; ibid., pp. 131–132; G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, pp. 297–300. [41] Z. Waźbiński, Mauzoleum Bony Sforzy w Barii, Przyczynek do dziejów polityki dynastycznej królowej Anny, ostatniej Jagiellonki, „Folia Historiae Artium”, 1979 s. 59–86; Jurkowlaniec finds Treter’s authorship to be a speculation not sufficiently founded in sources – G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość rycin…, p. 278. [42] Thus the aformentioned conclusions by Chrzanowski that Treter would only have been interested in emblems, polonica and images of saints. T. Chrzanowski, Uwagi o intelektualiście-kolekcjonerze…, p. 144; See also: T. Tretero, Symbolica vitae Christi meditatio, typis Georg Schoenfels, Brunsbergae 1612, foreword by Schoenfels. [43] Tomkiewicz, analyzing sixteenth-century accounts of pilgrimages to Italy, notices that Polish travelers did not pay particular attention to the name of the artist, the composition nor the proportions in the work of art. They were most impressed by monumentalism, the materials used as well as the pricing of a work of art. Similar conclusions are drawn by Lepacka in her analysis of the diary of Stanislaw Reszka, who was closely connected to Treter and Hosius; W. Tomkiewicz, Pisarze polskiego odrodzenia o sztuce, Wrocław 1955, pp. 44, 55–56, 85 ; Anna Maria Lepacka, Michel de Montaigne i Stanisław Reszka: o wrażliwości estetycznej humanistów podróżujących po Italii w drugiej połowie XVI wieku, in: „Relacje kulturalne między Italią a Polską w epoce nowożytnej”, pp. 49–75, Warszawa 2016, pp. 66–69. |

|

ALICJA BIELAK

VIDI DEUM FACIE AD FACIEM

EMBLEMATICS IN MARCIN HIŃCZA'S MEDITATIVE WORKS

|

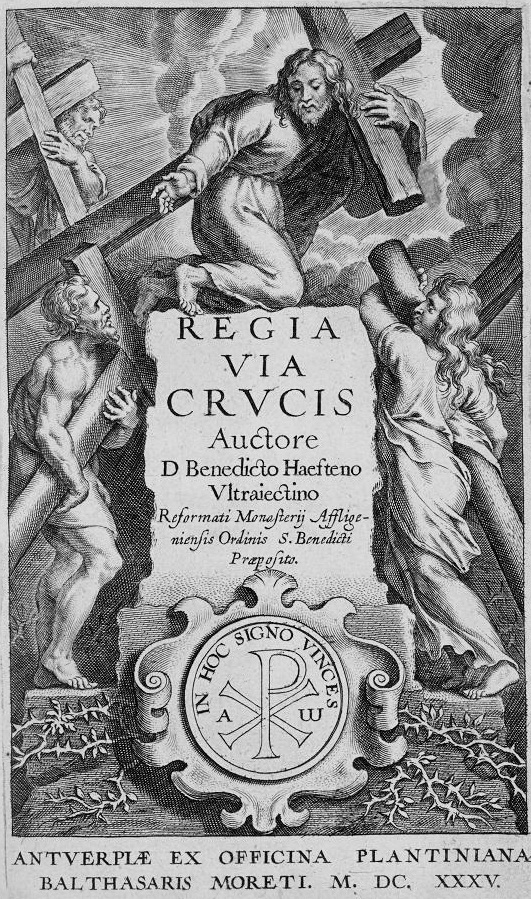

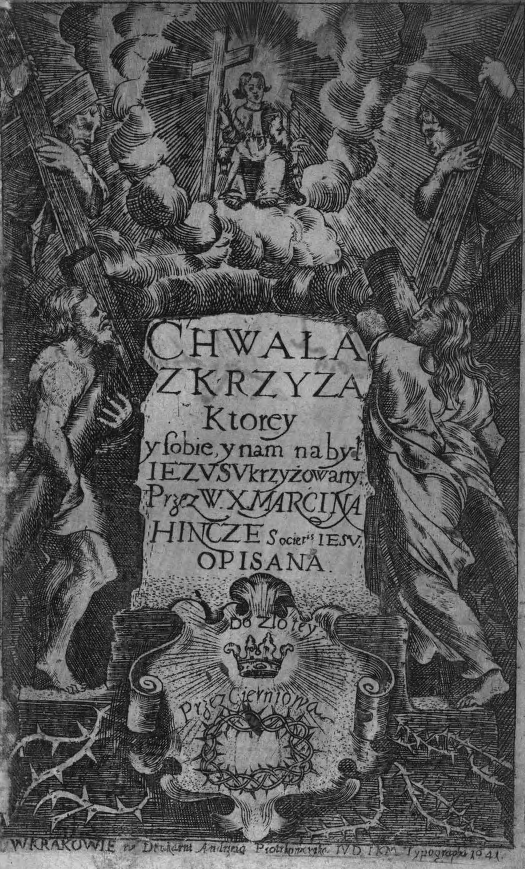

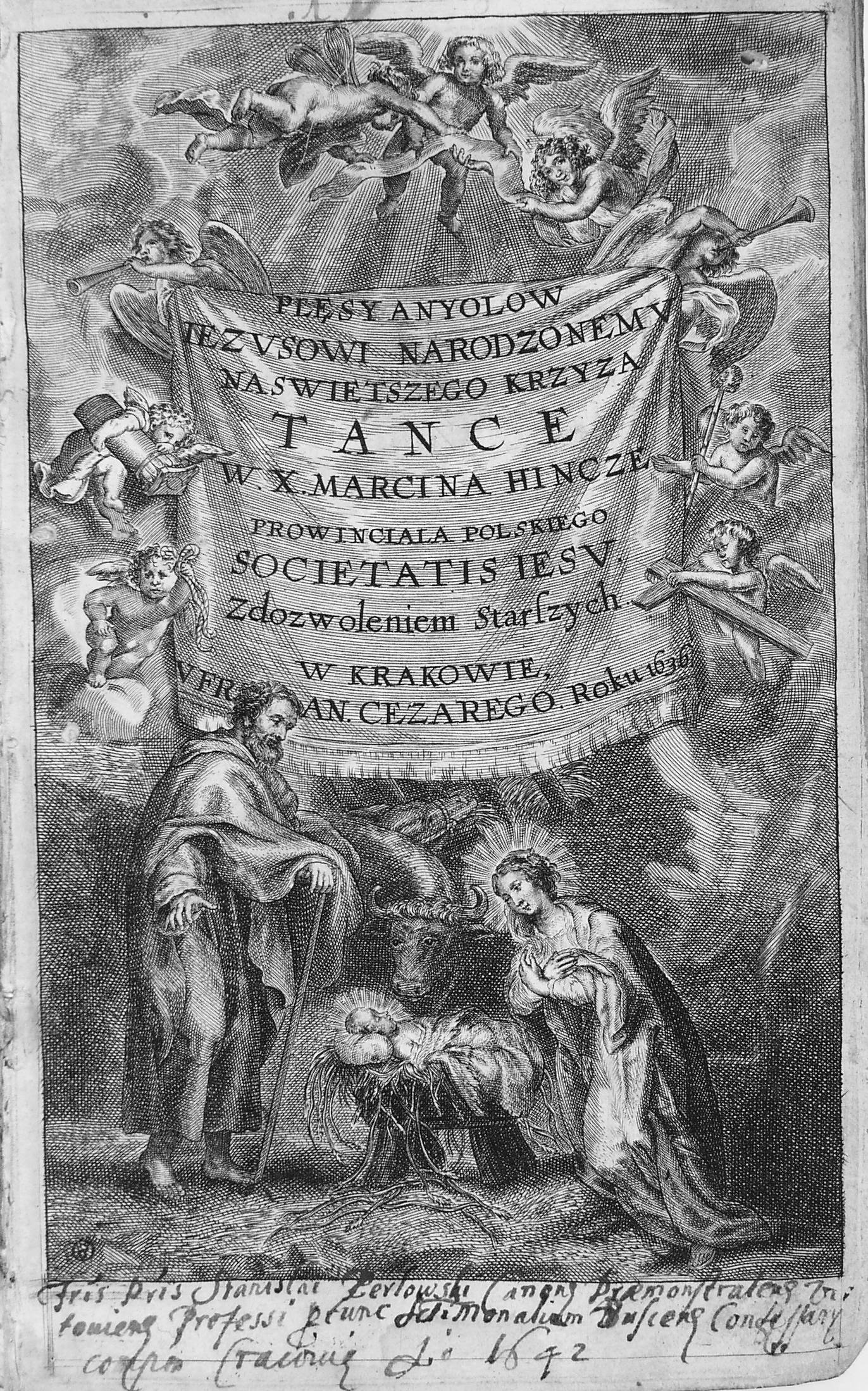

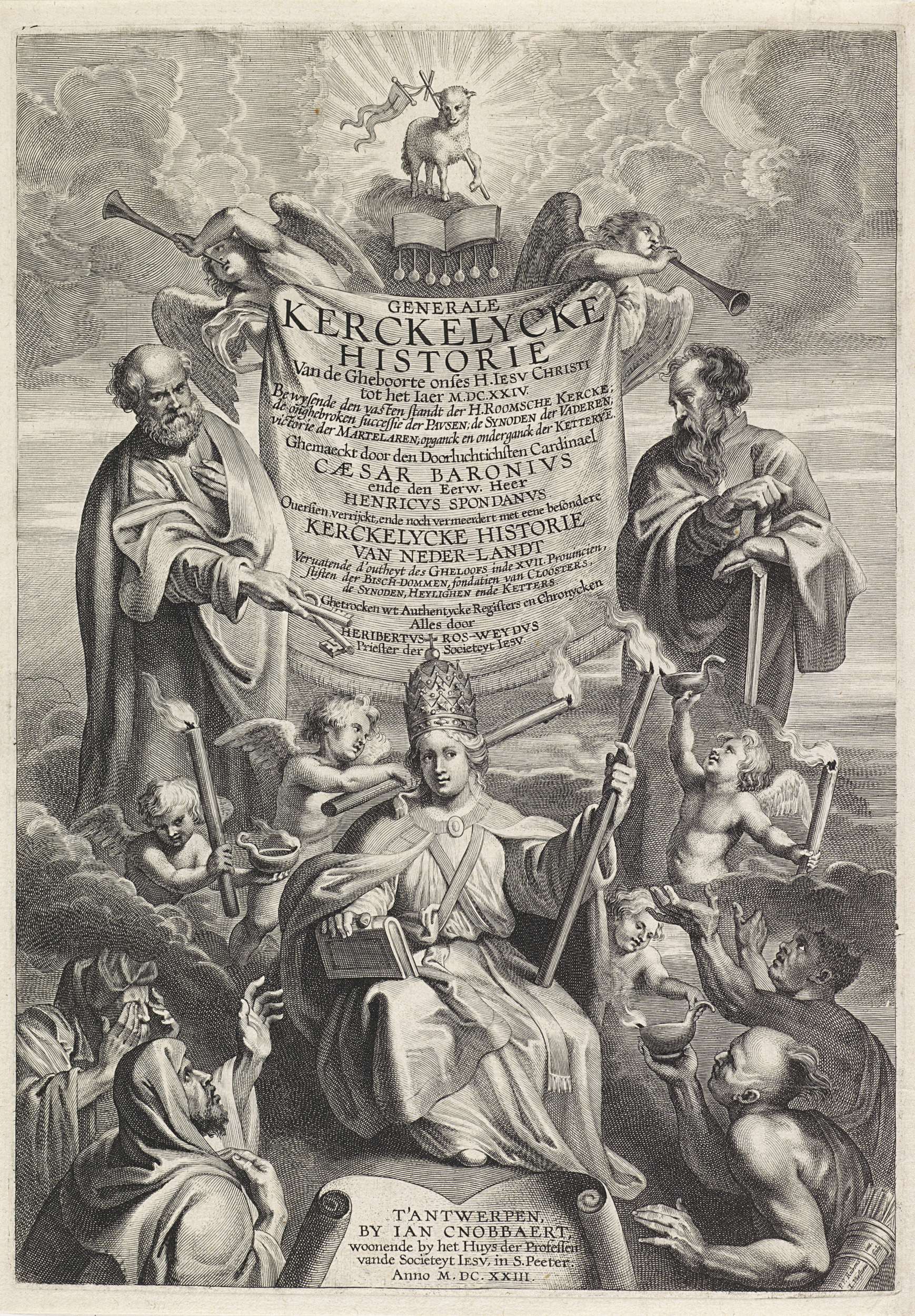

Les Emblèmes ou devises chrestiennes (Lyon 1567) by Georgette de Montenay, a Calvinist and lady in the court of Queen Joanne III of Navarra, is considered the first use of emblematics for religious purposes. After it was published, Catholic writers immediately realised how attractive and potentially useful for preaching this genre is. Thus, a subgenre of “sacred emblems” (emblemata sacra)[1] emerged. It mostly fascinated Jesuits, who published more emblematic volumes than any other intellectual movement. Around 1700 of their publications were emblematic, and if we were to draw a map of emblematic works created under the visible influence of a Jesuit model of piety or aesthetics, we would be obliged to add to that sum hundreds, if not thousands, of titles by lay authors and clergymen of different orders.[2] While pondering upon the various ways in which “Jesuit” emblematics were realised’, we should not forget about the specific status given to representatio in Ignatian piety: the realm of visible things was considered to have aesthetic, didactic and mnemonic values, but also an epistemological function: visibilia was always to point towards the invisible. All of creation was, according to Ignatius of Loyola, simply a veil for the transcendental – the realm of spirits both good and evil. A Christian should learn how to read their actions and distinguish between them. That way, he will be able to follow only what was given by God.[3] Emblem, watchwords and symbols became the objects of theoretical contemplation for Jesuits who, aside from noticing their persuasive character and using them for inventio (they were equated with imago figurata, a rhetorical trope), considered the possibility of using them as stimuli for explaining reality created ad imaginem Dei – in God’s image (Gen 1:26). Antoine Girard, a Jesuit, in the preface to his Les Peintures sacrées sur la Bible (Paris 1653) considered the Ignatian recommendation of “finding God in all things” the very core of The Society of Jesus’ thinking, seeing it as a call to use even the smallest elements of earthly matters for spiritual elevation towards God and remaining at his service. The theory of representatio, developed by Jesuits, assumed a strict parallel between the earthly world – a labyrinth through which the lost human soul paces – and the actual heavenly reality. The theory is too elaborate and complex to be explained here; I will limit myself to the description of issues that can aid in understanding the main assumptions and aims of the following sketch – the meditative and emblematic works of a Polish Jesuit, Marcin Hińcza.[4] Hińcza wrote six volumes of meditation in prose. Two of them were designed as emblematic cycles: Plęsy Jezusa z Anjołami (Jesus’ Frolics with the Angels, 1636–1638) and Chwała z Krzyża (Glory of the Cross, 1641). Illustrations for the Glory were taken by the publisher, Andrzej Piotrkowczyk, from several Dutch collections, mostly from Amoris divini et humani antipathia by Louis of Leuven[5] and Via regia Crucis by Benedict von Haeften (1588–1648).[6] The titular page was originally designed by Peter Paul Rubens himself (and made by Cornelis Galle). In the Cracovian publishing house it was altered significantly, probably at Hińcza’s request, so that the titular page would reflect the theological dimension of the piece. Jesus with a cross during the Passion (ill. 1) was replaced by the Infant Jesus sitting on a throne with a cross in his hand (ill. 2). This measure reflects quite well the style and meanings of Hińcza’s works; they focus almost entirely on the new-born Saviour. As has been determined by Anna Trejderowa, the 14 emblematic engravings placed in the Jesus' Frolics… were all made by a lesser known engraver from Theodore Galle’s school, Egidius van Schoor (Aegidius van Schoor or Gillis Verschoren).[7] Among the inspirations for them we can list Cornelius Thielmans and Augustus Suarez, but also such famous artists as Peter Paul Rubens, Antoon van Dyck, Joos de Momper, Otto van Veen (Venius) and other Flemish painters.[8] It is also worth mentioning that Van Schoor cooperated with Michael Snijders in publishing the aforementioned famous Amoris divini et humani antipathia as an engraver. Thanks to research conducted in Belgian archives it was possible to determine that the titular page of the Cracovian edition is a compilation of graphic motifs from books issued by Dutch publishing houses: angels blowing trumpets and presenting the cartouche or a cupid holding a candle; these motifs were probably taken from Generale Kerckelycke historie van de gheboorte onses H. Iesu Christi[9] by the Jesuit Cezary Baronius. One of the flying cupids with a column comes from an engraving titled Virtus Inconcussa, which opened a famous collection of Otto Vaenius’ Horatiana emblemata,[10] the sacred family with three angels above them comes from a woodcut by Bolswert Schelte Adamsz inspired by the Rubens painting (ill. 3-7). Connections with the aforementioned houses are not surprising if we consider the fact that printers from Cracow had close dealings with Dutch publishers.[11] A glance at emblematic prints stored in the archives, dating from the second half of the 16th century and the first decades of the 17th, legitimises the thesis of Hińcza having commissioned Van Schoor to create a series of engravings for Jesus' Frolics…. The topic of the volume is entirely original and there is no book from that period that would use a similar topic or graphics: presenting the crucified Christ as a child, not as a grown man, with angels revelling around the Cross. There is a strict connection between the text and the illustrations. The main subject of Hińcza’s meditative works is the birth (both primeval and earthly, from the womb of Mary), life, death and ascension of Christ with stress on the theological dimension of the Nativity and Incarnation. In two of the aforementioned volumes and in different ones created as part of Hincza’s early work (see Rozmyślania o dziecięctwie Pana Jezusowym [Thoughts on the childhood of Jesus], Cracow 1636) the dogmatic aspects are not discussed according to the vocabulary and rhetoric of theological treatises (so it is futile to look for terms such as “incarnation”[12] and developed references on the margins), although they consistently develop the concept of Jesus as Logos. It is certain though that Hińcza, as a professor of moral theology (he studied philosophy in Ingolsztadt, Rome and Kalisz and lectured in Cracow) was fully aware of all the nuances of Church dogma; for some reason, however, he decided not to refer to them directly in these works. He preferred to turn the dogmas of faith into stories or concepts. Reasons for this course of action can be found in the audience which he chose for his books, which were supposed to nourish piety in laymen. He stressed this himself in the prefaces, saying: “do not think I show these frolics to conventuals: they are both for preachers and for laymen to enjoy”.[13] Despite having drawn emblems from Regia via Crucis, a piece which expresses the idea of the bride’s soul travelling to find God’s love, a concept also known from Pia desideria, Hińcza does not present a simple reference to the themes and subjects of these works. The Glory of the Cross is almost a repetition of contents from the author’s earlier work – the Frolis…. The list of contents in the latter is an enumeration of values consequent on choosing the Cross – a symbol of salvation’s entire history – as one’s signpost: “enlightenment from the Cross”, “simplicity from the Cross”, “defence from the Cross”, “all venerations from the Cross”, etc. Similarly to Von Haeften, Hińcza enunciates the theology of the Cross, displaying its redemptive power in God’s plan,[14] but – which is unusual – does not stun the reader with the picture of the suffering Christ. To the meditator’s surprise, the Infant Jesus and all the angels surrounding him seem to rejoice at any sign of the nearing Passion. “Now the holy Angel creates an image of Christ’s future disgrace”. An emblematic icon accompanying the meditation acts as a compositio loci[15] and serves to make the reader emotional. At the beginning of every meditation, Hińcza observes the angel’s behaviour, is surprised by it and even execrates them: “do you know not, what tree is that? The one that will kill your Lord, and you are happy that he will die suffering?”, “you will get what is coming to you; believe me, the joy will turn to grief”.[16] By enumerating paradoxical images (birth – death, child – corporal punishment, Mary’s care – the seemingly aggressive behaviour of the Angels), Hińcza shows the reader that human perceptive abilities are not capable of processing the real meaning of the world that is a part of the Salvation plan. Every action of the angels Hińcza explains by their servitude to Christ on his way to fulfil God’s intentions. That plan only seems horrifying to people who still live according to categories of earthly reality. Hińcza’s angels then have the function of Christ’s perfect helpers, an image concurring with Ignatian piety: Loyola called angels God’s special help (auxilium speciale) due to the fact that they help men find the right path. It is worth stressing that this was a time of development of personal piety linked to the idea of guardian angels. Jesuits stressed the moral necessity of devoting oneself to one’s angel and the crucial role of mutual love of angels and humans in the economy of Salvation. To argument in favour of everyone having a personal guardian angel, they recalled the words of Christ (Mt 18:10): “See that you do not despise one of these little ones. For I tell you that their angels in heaven always see the face of my Father in heaven”[17]. The idea of seeing God the Father face to face implies an eschatological dimension: a soul, upon being saved, will be with the angels and will be able to look upon God’s face as he is being praised by heavenly hosts (Mt 18:10; see also Ex 33:11). But, as Christian mystics declared and Catholics of the post-Tridentine era repeated, following St. Paul, Jesus became visible for humans on earth to save them in the name of marital love and to show his face, which is – paradoxically for the Christological representation – at the same time the face of his Father (cf. 1 J 3, 2).[18] Hińcza also stresses this change in God’s visibility that occurs with the coming of Christ. He recalls of those enlightened by the brightness of the crucified Christ that “they [Apostles – A.B.] then enlightened the world and brought it to realise the truth (1 Cor 1)”. He also notes that the angels “all trembled before Thy glory in heaven, and on earth it is as if they have forgotten it […] God forbid they should step down from the place designed for them, away from his visage – all would fall into the abyss. Everyone knows what happened to the numerous angels who thought of being equal to the Creator”.[19] The idea behind Frolics... corresponds to Robert Bellarmin’s De Ascensione mentis in Deum (1615), translated into Polish by Kasper Sawicki in 1616.[20] The cardinal describes fifteen consecutive steps to knowing God, starting with his creation (which God – himself unable to see, according to Bellarmino – created for humans), and it ends with the description of the sun as the most beautiful thing visible, which corresponds to the cosmological vision introduced at the beginning of Hińcza’s piece: a cosmic dance of stars (angels) and moon (Mary) around the sun (Jesus, also described as “brightness”).[21] Bellarmino adapted a neo-Platonic mode of thinking, saying that looking at sun and stars brings joy and their movement resembles dancing: “all of them in their beautiful order run, tireless, in a circle, looking as if they were dancing”.[22] The next steps of recognition are only a part of the invisible world: a man should initiate this stage by looking into his own soul (the part most resembling God’s nature), then consider the nature of angels and, finally, the features of God (the Jesuit keeps stressing the role of sight in all these stages: to know God one must look upon the angels). An angel’s sight is vastly different from a man’s, because “an angel can immediately perceive and understand what he sees, and realise what comes of it”.[23] In conclusion, Bellarmino teaches us that the simplest way to the Kingdom of Heaven is “where we perceive together with the angels, as they always look upon the Father’s face”.[24] In the Frolics... angels repeat the gesture of God’s heavenly worship, the possibility of looking upon His face: “they do not take their eyes from Him, and the more different from the divine and human nature his features become, the more intently angels look at Him, to learn this odd secret – that God even in such a humbled form is full of greatness”.[25] The soul, looking at angels while praying, is at first surprised and only later starts to understand that it should follow them in their contemplation of Jesus (Hińcza also maintains the metaphor of the cosmic dance, which we cannot address here).[26] Looking at Christ, it follows his example but also wants to be seen by its Beloved as pure and like Him: “Oh Man full of love (= Jesus – A.B.), make it so that all heavenly and earthly beings could say about me that ‘this man wants to be like You in his loving’”.[27] The dynamics of exchanged looks between the meditating soul and Jesus, described vividly in Hińcza’s works, is developed for example in the meditative emblematic works of the Spanish humanist and theologian Benito Arias Montano. In his cycle entitled Divinarium nuptiarum conventa et acta (Atverpiae 1573),[28] Montano, basing his perspective on the Song of Songs, writes out a drama taking place between the Bride (Sponsa) – i.e. the Soul – and the Groom (Christ). For the marriage to happen, however, the soul must be cleansed of its sins and understand its paltriness. Wisdom Personified (Scientia) tells her to look into a mirror that will allow her to see her true visage. The Bride sees all the futility of the world, vanity and craving for earthly honours. The Bride, exhausted by this sight, rests upon the bosom of Wisdom and then looks upon another mirror in which she only sees the face of Christ. The paraenetic dimension of this visage is an obvious context for the collection: speculum vitae Christi becomes synonymous with meditation itself. Only when the Bride decided to live virtuously, following the example of Christ, wiped out her own, sinful reflection from her soul and replaced it with His face in the name of imitatio Christi, does she experience marital love and connect with the beloved.[29] The words of Paul from the First Letter to the Corinthians (13:12) provide context for these words. He says that on earth “For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known” (ESV). Hińcza acts similarly when showing the moment when Mary looks into Christ’s face: “she sees the awfulness and sin taken from human faces stain the visage of her Son […] She will see her soul and know that for that ugliness of her Son’s she has an ornament above all others”.[30] The ugliness is a result of Christ’s whipping, and becomes the reason for human righteousness – thus an ornament. This is compatible with the aim of Ignatian meditation, which is supposed to incarnate Christ’s presence – his re-presentation in the memory, mind and heart of the meditating person – in order to take an example from him (imitatio) not only by means of compassion (compassio), but also by observation, which drives the meditator to understand and feel guilt: “Every soul which glances upon the tortured Christ will see that he has been beaten and hurt for them and by them”.[31] The moment a person understands that Jesus died because of his love for people (the Ignatian via illuminativa), he will cleanse himself of his sins (via purgativa), and then he will start to imitate Christ (via unica): “strive to be like Christ, struggle to follow him, for he is given unto you as an example”.[32] Angels are for Hińcza an example of the perfect spectators, subjects and admirers of Christ. They gaze upon him incessantly and joyfully, repeating the act of adoration in heaven of the first person of the Trinity (ill. 9). Christ’s descent (the descent of the Logos) is an act of his adoration and love for men: he puts himself in plain sight so that man can follow his example in his earthly peregrination. A glance at the role of sight in the meditative works of Hińcza makes it clear that he was perfectly acquainted with the problems explored by Jesuit theologians and artists, whose works he developed so skilfully. In the context of the aforementioned Dutch emblematic art, Hińcza was certainly well acquainted with contemporary artists, who not only borrowed from others, but were also able to rework their art. Moreover, like other Jesuit authors he could be creative in the use of emblems not just as illustrations but also as performative tools for the action of seeing, so important due to the epistemological aspect of Ignatian meditation and its theological connotations.

Translated by Zofia Marcinek

[1] In the titles of emblematic collections and in the prefaces to those volumes we encounter the term emblema sacra, which denotes a broad and differentiated spectrum of realisations: moralising symbols and watchwords (see Emblemata sacra by Daniel Cramer from 1624 or Guillelmus Hesius’ Emblemata sacra de fide, spe, charitate from 1636), illustrations of events from the gospels (a famous, prolifically reissued collection by Jeronimó Nadal entitled Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia), illustrated lives of saints and martyrs, ascetic collections developing piety, and others. [2] Corpus Librorum Emblematum: The Jesuit Series, ed. P. M. Daly, G. R. Dimler, University of Toronto Press, vol. I–V: Toronto 199–2007. [3] R. Dekoninck, Ad Imaginem: Status, fonctions et usages de l’image dans littérature spirituelle jésuite du XVIIe siècle, Genève 2005. [4] A full analysis of the theme of the Incarnation and of its influence on the Jesuit theories of representation and image has been conducted and propagated by two excellent researchers: Ralph Dekoninck and Walter S. Melion. See R. Dekoninck, op. cit.; W.S. Melion, Meditative Art: Studies in the Northern Devotional Print, 1550-1625, Philadelphia 2009; Meditative art Image and Incarnation, ed. W. S. Melion, L. P. Wandel, Brill, 2015; Jesuit Image Theory, ed. W. de Boer, K. A. E. Enenkel, and W. S. Melion, Brill, 2016. [5] Ludovicus van Leuven, Amoris divini et humani antipathia, Apud Michaelem Snyders, Antwerpiae 1626, 1629. [6] Benedictus von Haeften, Via regia Crucis, Antverpiae: ex officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1635. The basics for the icons in Boetius of Bolswert’s works in the case of Chwała z Krzyża and the fact that the engravings for Plęsy were made by Egidius van Schoor were noted by Anna Treiderowa; see Ze studiów nad ilustracją wydawnictw krakowskich w wieku XVII (z drukarń: Piotrkowczyków, Cezarych, Szedlów i Kupiszów), “Rocznik Biblioteki PAN w Krakowie”, 1959, 5, p. 37–38. See also J. Pelc, Słowo–obraz–znak. Na pograniczu literatury i sztuk plastycznych, Universitas, Kraków 2002, p. 196–204. [7] See Hollstein et al, vol. 26: 1982, p. 47–49. He does not count Frolics... among the books illustrated by Van Schoor, just as he does not mention such pieces as De naer-volginge des doodts ons heeren Iesu Christi by Nicolaus Georgius (Tot Brusel: bij Ian Mommaert, 1650) or the collection by Nicolaus Ianssenius entitled Vita P. P. Dominici ordinis praedicatorum fundatoris (apud Heicum Aertssium, Antverpiæ 1622), which we know were made by Van Schoor because of his signature: “G. V. Schoor f[ecit]”. Van Schoor is also not mentioned in encyclopaedias of Dutch printing and engraving. [8] Kunstschilders, beeldhouwer, graveurs en bouwmeesters, Gebroeders diederichs, v. 2: P–S: ed. C. Kramm, Amsterdam 1861, p. 96. [9] C. Baronius, Generale Kerckelycke historie van de gheboorte onses H. Iesu Christi, Ian Cnobbaert, T’Antwerpen 1623 (engraver: L. Vorsterman). [10] O. Vaenius, Horatiana emblemata, apud Philippum Lisaert, Antverpiae 1612. [11] The editor of Glory..., Andrzej Piotrkowczyk, went to the Netherlands himself as the preceptor of the Radziwiłł family and cooperated with the greatest men of the contemporary literary scene. In Leuven he studied rhetoric in Erycius Puteanus’ school; the latter praised him in personal letters to Daniel Heinsius (see M. Czerenkiewicz, Belgijska sarmacja, staropolska Belgia, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Warszawa 2013, p. 61). See also P. Buchwald-Pelcowa, J. Pelc, Rola jezuitów w kształtowaniu się związków emblematyki polskiej z emblematyką niderlandzką, “Barok”, 2003, nr 20, p. 9–32; M. Malicki, Repertuar wydawniczy drukarni Franciszka Cezarego starszego 1616–1651. Część 1, Wydawnictwo Księgarnia Akademicka, Kraków 2011; W. Ptak-Korbel, Andrzej Piotrkowczyk II, in: Drukarze dawnej Polski od XV do XVIII wieku: praca zbiorowa, vol. 1: Małopolska, p. 2: Wiek XVII–ZVIII, vol. 2.: L–Ż i drukarnie żydowskie, ed. J. Pirożyński, Kraków 2000. [12] To clarify, in the entire 700-page book the phrase “the incarnated Word ” appears once (M. Hińcza, Plęsy… Kraków 1638, p. 349). [13] Ibid., p. 31. More consistent, casuistic theological investigations can be found in his older works – the meditative volume Matka Bolesna Maryja and Glos Pański… Thus, when analysing pieces by a doctor of theology – including those from the 1630s, which are repetitive and very sensual, and which apply all spiritual experiences to human senses (in accordance with the Jesuit applicatio sensuum rule) – we should also try to find messages and arguments not expressed explicitly. [14] Similar contents can be found in the writings of Kasper Drużbicki, with whom Hińcza was acquainted. See J. M. Popławski, Kaspra Drużbickiego teologia Krzyża, Redakcja Wydawnictw Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego, Lublin 1997. [15] On the functions and types of composition of place in Loyola’s Spiritual exercises see especially P.-A. Fabre, Ignace de Loyola: Le lieu de l’image. Le problème de la composition de lieu dans les pratiques spirituelles et artistiques jèsuites de la seconde moitiè du XVIe siècle, Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales et Librairie Vrin, Paris 1992. Nota bene Loyola often demands in addition that readers should picture themselves in the presence of God, saints and angels. [16] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 90, 657, 656. [17] At the time, angelology in the Jesuit Society was mostly pursued by, among others, Jeremias Drexel and Cornelis a Lapide. Originally it was initiated by Bellarmin’s favourite, Alojzy Gonzaga, who died before his time; Gonzaga was the author of angelic meditations. Trevor Johnson stressed that angelology from the turn of 16th century often contained motifs that may seem dogmatically controversial. See T. Johnson, Guardian Angels and the Society of Jesus, in: Angels in the Early Modern World, ed. P. Marshall, A. Walsham, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, p. 191–213. [18] The Holy Face and the Paradox of Representation, ed. H. L. Kessler, G. Wolf, Nuova Alfa Editoriale, Roma 2000; W.P. Melion, Haec per Imagines huius mysterij Ecclesia Sancta [clamat]: The Image of suffering Christ in Jerome Nadal’s Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia, in: J. Nadal, Annotations and meditations on the Gospels, v. II: The Passion narratives, tr. and ed. F.A. Homann, preface by W. P. Melion, Saint Joseph’s University Press, Philadelphia 2007, p. 1–73. [19] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 29–30, 89. [20] R. Bellarmino, De Ascensione mentis in Deum per scalas rerum creatarum opusculum, Ex Officina Plantiniana, Antverpiae 1615; R. Bellarmino, Piętnaście Stopni, po których człowiek, zwłaszcza krześcijański, upatrując Pana Boga w stworzeniu rozmaitym, przychodzi do wielkiej znajomości jego, tr. Kasper Sawicki, Kraków 1616. [21] On the cosmic dance of angels in Frolics… see A. Bielak, Taniec na Golgocie w medytacyjnym zbiorze „Plęsy Jezusa z aniołami” Marcina Hińczy, “Tematy i Konteksty” 2016, nr 6 (11), p. 302–316. [22] R. Bellarmino, Piętnaście stopni..., p. 112. [23] Ibidem, p. 126. [24] Ibidem, p. 128. [25] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 42. [26] On the development of the subject of stellar angelic hosts praising God in the heavens see J. Miller, Measures of Wisdom. The Cosmic Dance in Classical and Christian Antiquity, University of Toronto Press, Toronto-Buffalo-London 1986, p. 345–360, 391–401. [27] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 455. [28] The cycle may be found in the volume A. Montanus, Christi Iesu vitae admirabiliuque actionum speculum (engraver: P. Galle). [29] See W. P. Melion, Love, Judgment, and the Trope of Vision in Benito Arias Montano’s “Divinarum nuptiarum conventa et acta” and “Christi Iesu vitae admirabiliumque actionum speculum”, in: ibid., The Meditative Art. Studies in the Northern Devotional Print: 1550–1625, Saint Joseph’s University Press, Philadelphia 2009, p. 39–105. [30] M. Hińcza, op. cit., p. 326–327. [31] Ibidem, p. 456. [32] Ibidem. |

Ill. 2. M. Hińcza, Chwała z Krzyża której i sobie, i nam nabył Jezus ukrzyżowany, w drukarni Andrzeja Piotrkowczyka, Kraków 1641, titular page (Chełmska Biblioteka Cyfrowa)

Ill. 7 7. M. Hińcza, Plęsy Anjołów Jezusowi Narodzonemu, naświętszego Krzyża tańce, u Franciszka Cezarego, Kraków 1638 (University of Warsaw's Library, sygn. Sd.712.583)

|

BARTŁOMIEJ CZARSKI

ANDREAS ALCIATUS AND BONA SFORZA:

IN PURSUIT OF THE OLDEST TRACES OF „EMBLEMATUM LIBER” IN POLAND

|

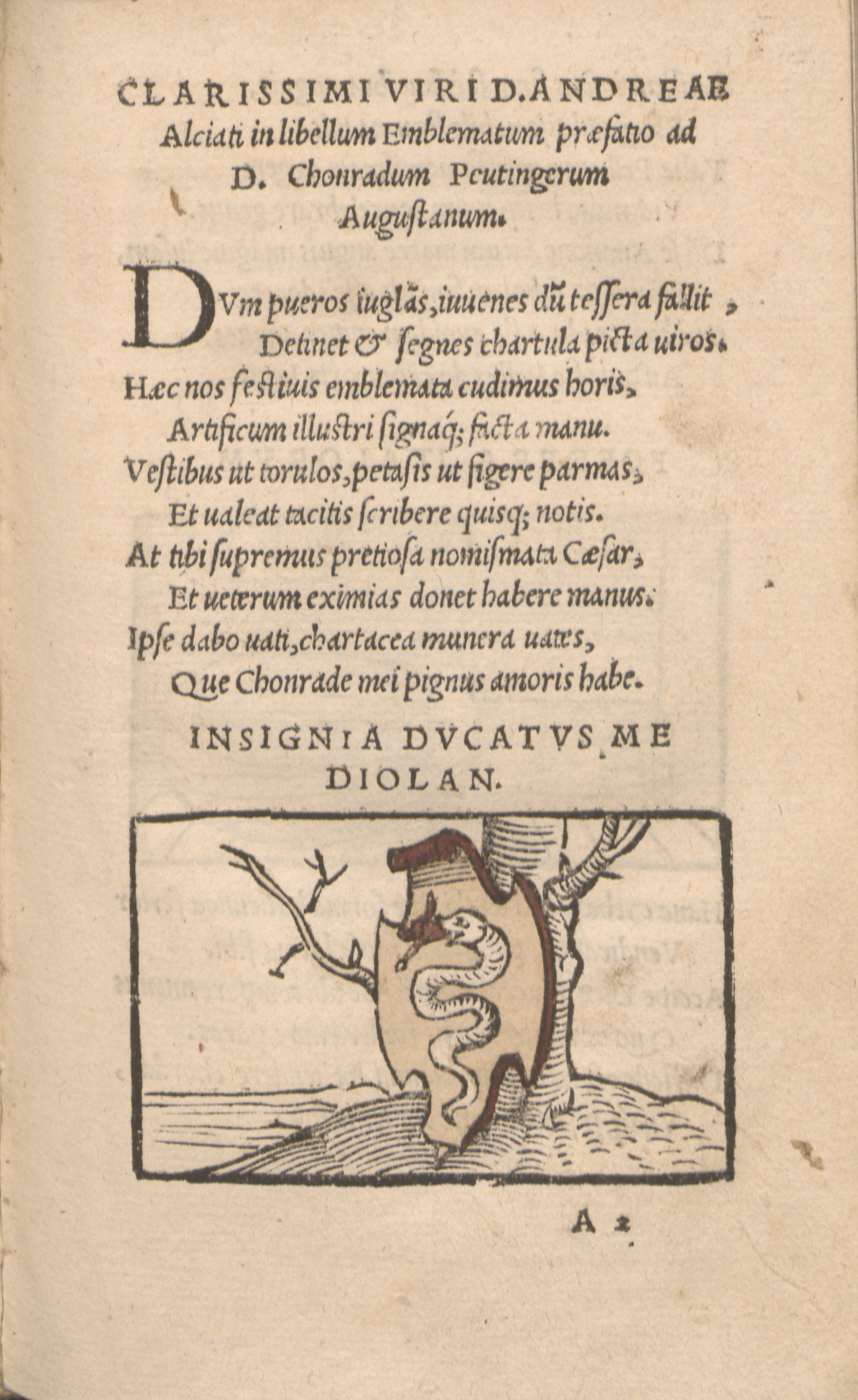

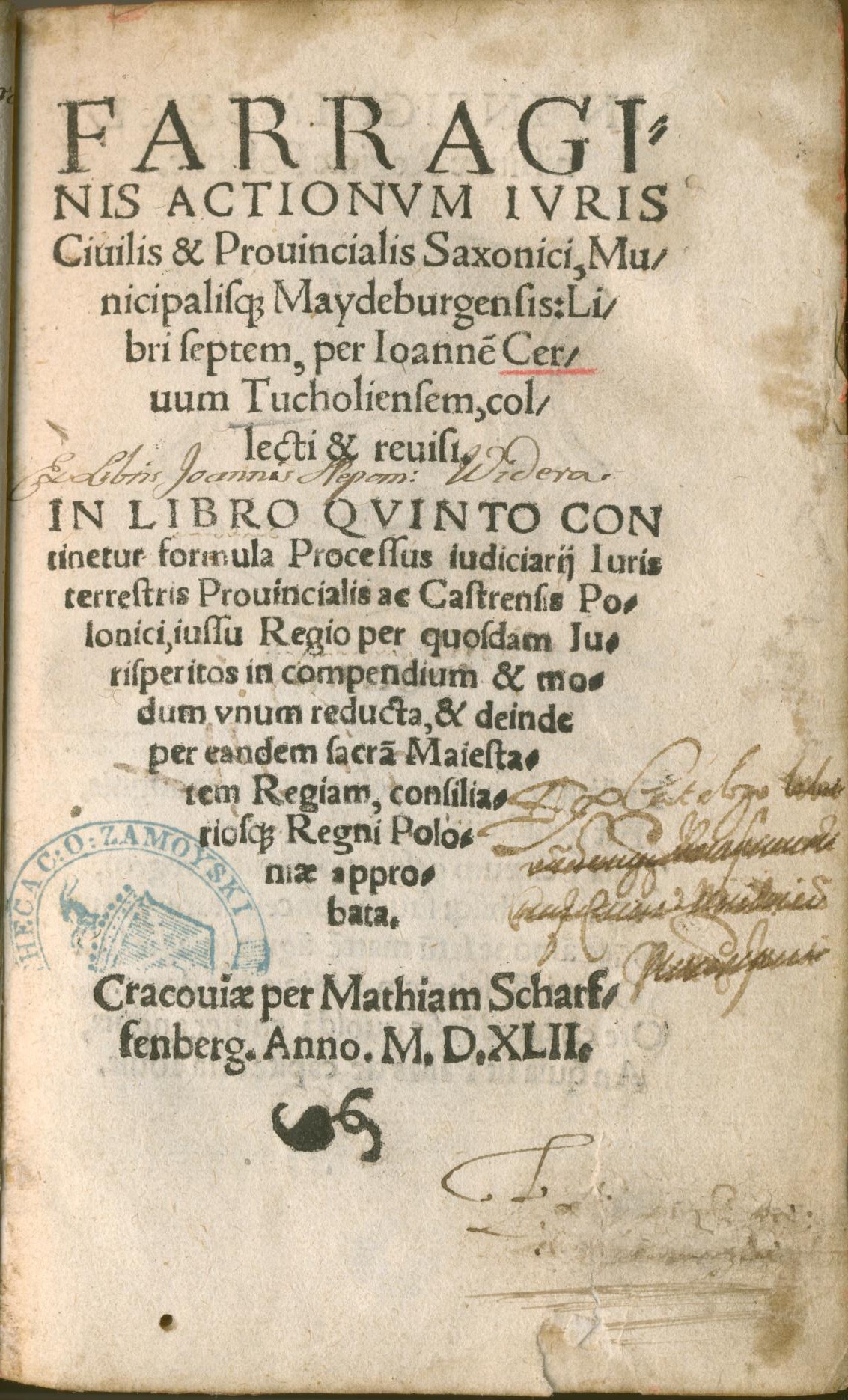

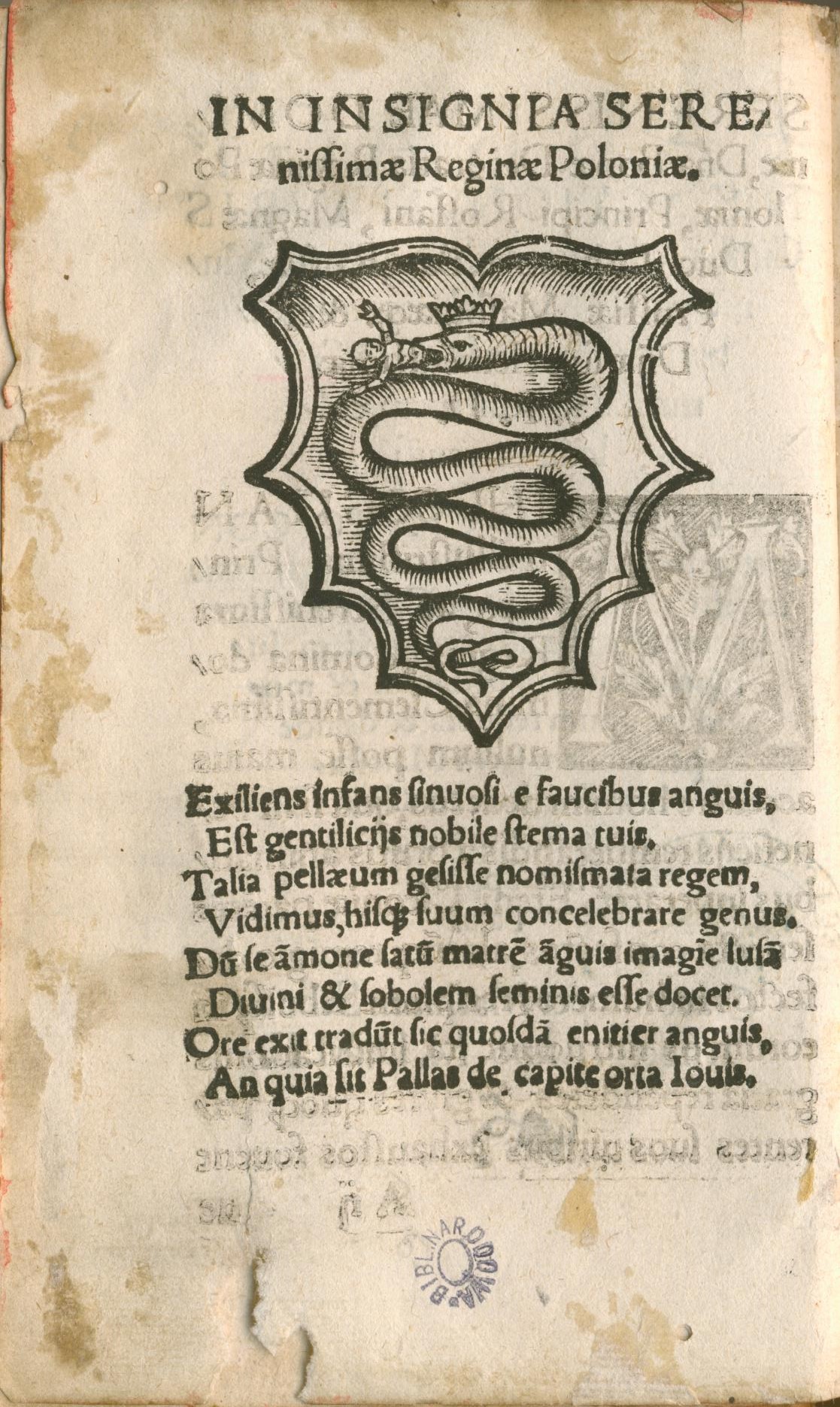

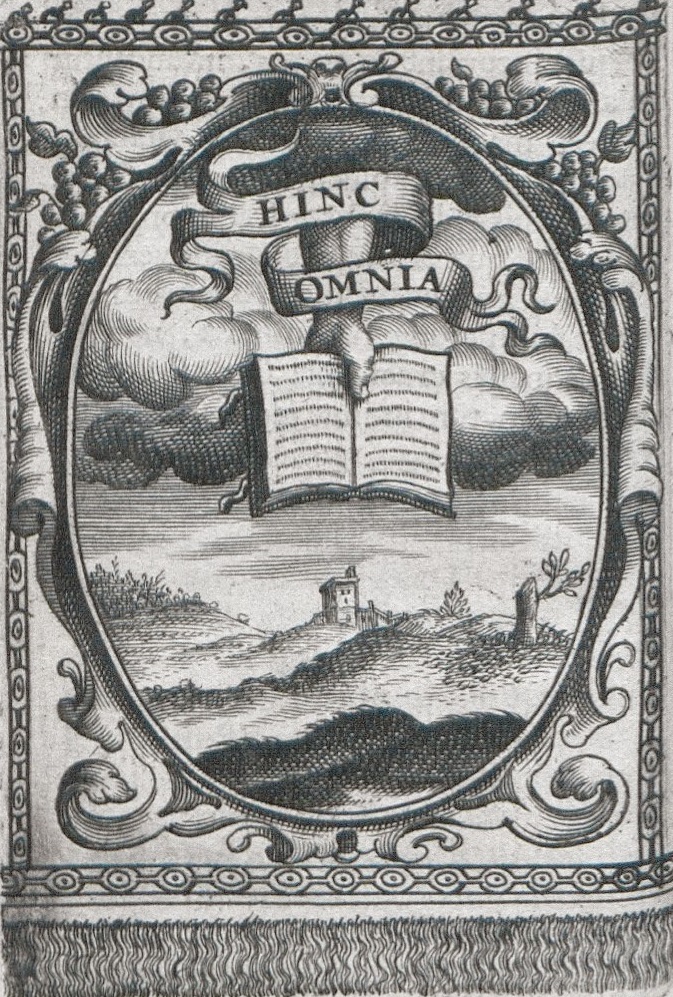

Verbal and visual compositions in Polish print appeared very early, usually in the form of stemmata – verses adorning coats of arms. They were usually accompanied by a wood engraving representing an emblem relating to the epigram in question.[1] It was also common to add verses to images of saints or various icones. The oldest cases can be traced back to the dawn of the 16th century,[2] and are thus older than the 1531 Emblematum Liber[3] by Andreas Alciatus (Andrea Alciato/Alciati), a collection commonly considered to be the first emblem book: the history of European emblematics begins with its release (Ill. 1). The author was a famous lawyer, a lecturer in Padova, Bologna, and Ferrara, as well as in France, in Avignon and Bourges.[4] He is mostly remembered for this initially minor volume containing 104 emblems (of which 97 are illustrated). It was published for the first time in the publishing house of Heinrich Steyner and later reissued and extended (finally reaching 212 emblems) by various editors and interpreters. The estimated number of issues published by the end of the 17th century is over 170.[5] The collection contains epigrams inspired by traditional European motifs drawn from mythology, the Holy Bible, fables, Greek and Roman literature and ancient relics such as architectural details, gems and coins preserved until the 16th century. At that time, these objects were an object of interest and passion to intellectually sophisticated collectors.[6] It is a topic of discussion among modern scholars whether the graphics were chosen by the author himself, or whether someone else decided which graphics would accompany the epigrams.[7] Regardless, the engravings became a fixed part of the emblems. Together with the verse and the titular motto, they constitute the three elements of the most common emblematic structure. Some of Alciatus’ works, partly because of the accompanying engravings, bear resemblance to the aforementioned stemmata. The opening poem could be mentioned here: in the editio princeps it was entitled Insignia ducatus Mediolanensis [The emblem of the Milan Duchy] (see ill. 2). In later editions it was treated as a form of dedication and was meant for Prince Maximiliano Sforza, as can be deduced from how the title was modified: Ad illustrissimum Maximilianum ducem Mediolanensen (To the honourable enlightened Maximiliano, Prince of Milan).[8] Alciatus had an inestimable influence on European literature. After his publications, emblems started to appear in the works of various authors, and to have a great influence on contemporary culture. Nonetheless, despite considerable evidence that Emblematum Liber was well known in 16th-century Poland, it is hard to trace its first direct influence on Old-Polish literature. Since heraldic compositions became a more popular and prolific emblematic form in Poland than anywhere else, one might suspect that Alciatus’ most famous compositions would be the ones related to heraldic motifs. But it is also important to remember that the appearance of stemmata and emblematic verse is not limited to Poland. They can be encountered elsewhere, and also earlier than in the Kingdom of Poland. One such example is Hieronim Wietor, a Viennese printer who later moved to Cracow and launched a prosperous publishing house there.[9] It seems reasonable to suppose that it was his books, largely meant for the Polish publishing market, that made emblems so popular in Cracow. Other publishers soon became interested in them as well – Florian Ungler,[10] the Szarffenbergs, and Jan Haller,[11] who was a publishing monopolist for quite some time. Even if heraldic compositions in Poland can be dated earlier than the official birth of European emblematics, it is valuable to try to find the earliest instances of the reception of Alciatus’ work, if for no other reason than the volume’s status as the first emblematic publication. Verses adorning coats of arms became fashionable at the beginning of the 16th century. It is for this reason that the above-mentioned emblem with a dedication, created upon the coat of arms of the Milanese royal family, drew attention in Poland. Its first uses can be traced back to 1542, just 11 years after Emblematum Liber was published. Cracovian printer Maciej Szarffenberg used it as a stemma added to a special dedication for Queen Bona Sforza, in a legal treatise written by Jan Tucholczyk (Ioannes Cervus) entitled Farraginis actionum iuris civilis et provincialis Saxonici municipalisque Maydeburgensis libri septem[12] (Ill. 3). Interestingly, the circumstances of this publication are criminal, because Szarffenberg stole a new version of Tucholczyk’s text from the workshop of Helena Unglerowa (the wife of Florian Ungler) and published it in 1539, before Unglerowa had time to release her own version.[13] Unglerowa lodged a complaint against Szarffenberg to the City Council and as a result the case came before the royal court. Thanks to the intervention of Queen Bona, Szarffenberg ultimately managed to avoid serious consequences. In gratitude for her protection, the next edition of Tucholczyk’s dissertation (in 1542) was dedicated to the wife of Sigismund the Old. The Cracow typographer decided to reprint the work in 1546; on this occasion also, he included the stemma with Alciatus’ epigram, in exactly the same form as in the 1542 publication. It is difficult to clearly explain the reason for the queen’s intercession. It was perhaps due to efforts on the part of the printer’s wife, Helena Szarffenbergowa, who enjoyed the sympathy of the queen in later years also.[14] Only the verse from Alciatus’ emblem was used. The publisher added a wooden engraving of the Sforza family crest to it and – obviously – omitted the title. The epigram used in the new context could no longer be associated with Milan or Prince Maximiliano. It was meant to draw attention to the Polish queen. It may also be the reason why the verse was reproduced without mentioning the author’s name – to erase the primary meaning of the emblem completely. The verse itself explains their family crest in an allegorical manner, praising the family:

Exiliens infans sinuosi e faucibus anguis,